Idaho Public Defense Workload Study

Report Authors

- Vanessa Cosgrove Fry, Assistant Director

- Sally Sargeant-Hu, Research Associate

- Lantz McGinnis-Brown, Graduate Research Assistant

- Greg Hill, Director

This report was prepared by Idaho Policy Institute at Boise State University and commissioned by the Idaho State Public Defense Commission.

Recommended citation: Fry, V. C., Sargeant-Hu, S., McGinnis-Brown, L., & Hill, G. (2018). Idaho Public Defense Workload Study. Idaho Policy Institute. Boise, ID: Boise State University.

Download a printable pdf of this report

Executive Summary

Many states have conducted workload studies for the purpose of developing caseload standards that are tailored to their own legal environments. This report is the culmination of a year-long study of the workload associated with providing public defense in Idaho. The study tracked how much time Idaho attorneys spend on specific tasks associated with indigent defense cases as well as attorneys’ perceptions of the average amount of time specific tasks and cases require for adequate and effective defense. This is the first time Idaho-specific data regarding indigent defense workloads across the state has been collected and analyzed. This report does not prescribe indigent defense workload standards; rather, the information presented here, and the data supporting it, is intended to inform future discussions and decisions made concerning caseload guidelines for Idaho’s public defense system.

Introduction

Under the 6th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the accused have the right to have a lawyer advocate for their stated interests. In cases where the accused cannot afford to hire private counsel, the state is obliged under the 14th Amendment to provide effective representation at all critical stages of a criminal or delinquency proceeding in which a person may potentially lose his liberty.1 Although the U.S. Supreme Court has never been asked to clarify whether a state may constitutionally pass on that obligation to local governments, the state remains responsible for ensuring that local governments meet the parameters of 6th Amendment case law. Idaho does not have a statewide public defense system, rather indigent defense is primarily managed at the county level by appointed defense attorneys.2 Oftentimes, states have codified commissions to help advise the public defense system, despite jurisdictional level of management.

In 2014, the Idaho Legislature passed House Bill 542, creating the Idaho Public Defense Commission (PDC), and House Bill 634, providing funds for the commission to begin its work. Per Idaho Code 19-850, the PDC has been tasked with the responsibility of promulgating administrative rules related to Idaho’s public defense system, including:

- Training and continuing legal education for defending attorneys,

- Uniform data reporting requirements and model forms,

- Model contracts for counties and defending attorneys,

- Administration of appropriated funds for counties’ delivery of indigent services,

- Standards for defending attorneys, and

- Procedures for oversight, implementation, enforcement and modification of indigent defense standards.

In 2017, the PDC created the first set of standards for indigent defense attorneys. To promulgate additional rules, the PDC recognized a need for additional Idaho-specific data beyond the annual reports public defenders submit to the PDC. Thus, in 2017 the PDC contracted with Boise State University’s Idaho Policy Institute (IPI) to conduct a study designed to investigate public defense attorney workloads. The goal of the study was to provide a body of Idaho specific data and information to the PDC to inform their recommendations concerning caseload guidelines and future workload standards for Idaho’s public defense system. IPI’s research team designed and implemented the study. This report to the PDC documents the study’s methodology and the research team’s findings.

Return to the beginning of the report

As academic researchers, IPI designed this research methodology to ensure reliable and accurate findings based on the specific nature and limitations of this particular study. The research design for this study was informed by thorough review of other workload studies,3 consultation with national experts and academics, and review of relevant literature, which is provided in Appendix A as a bibliography. Although past studies were consulted, this study was designed and implemented specifically for Idaho and the unique characteristics of its public defense system.

Public Defense in Idaho

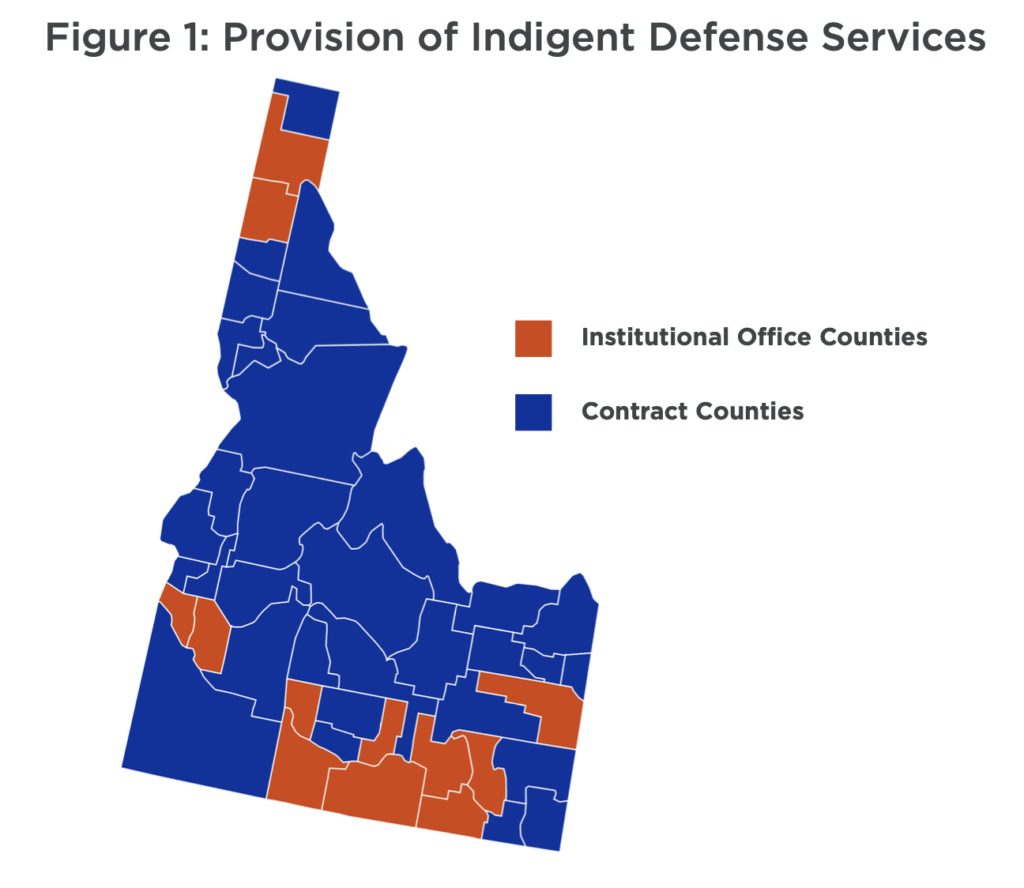

As mentioned, Idaho does not have a statewide public defense system; rather indigent defense is managed at the county level. Of Idaho’s 44 counties, 32 counties contract out to private attorneys to provide public defense services.4 The remaining twelve counties have institutional offices where the public defense attorneys are county employees.5 Figure 1 maps the provision of indigent defense in Idaho. Whether a county contracts for services or has an institutional office, each county also works with conflict attorneys who provide public defense, via a contractual relationship, when institutional or contract attorneys have a conflict of interest. Counties in Idaho with the highest population are the counties with institutional office. These counties can be considered more urban, whereas the remaining counties with contract attorneys have a smaller population and, thus, are more rural. As may be expected, counties with higher populations also have a higher annual caseload than more rural counties.

With public defense management in the control of the counties, there has not been a consistent, statewide method in place to capture attorney workload; beyond the annual report counties are statutorily required to submit to the PDC.6 Most counties have not implemented a method for tracking attorneys’ time. Therefore, although the number of cases an individual attorney carries each year is known, neither the total time, nor the type of time the attorney spends on each of those cases, is known. In addition, until this study, data on the perception of attorneys regarding their workload, perception of time needed to deliver defense, and available resources was not available.

To help address the gaps in knowledge outlined above, the research design process for this project included developing specific research questions. The research questions outlined to guide this study included:

- How are Idaho’s public defense attorneys currently spending their time on cases?

- How do public defense attorneys perceive they are spending their time on cases?

- How do public defense attorneys perceive the sufficiency of the time they spend on cases?

- What do public defense experts in Idaho perceive to be an acceptable standard for specified case loads?

Taking into consideration funding and time constraints, the research team then determined the methodologies best suitable for addressing those questions. Therefore, a mixed methods approach was employed in order to provide the most robust picture; the quantitative data informs the “how,” the qualitative data informs the “why.” Without both, future decision-making around workload standards would be of limited utility. The quantitative components of this project – the Time Tracking and certain aspects of the Time Sufficiency Survey –illustrate how attorneys may be spending their time and how they perceive time should be spent. Meanwhile, the qualitative aspects of this project – sections of the Time Sufficiency Survey and the Delphi process – provide the narrative behind the numbers, thus revealing the contributing factors to specific numeric outputs of both measured and perceived time. Both components are necessary for the PDC to understand how attorneys are spending their time and why, thus enabling future recommendation and decisions to informed by Idaho-specific workload data.

In addition to providing qualitative information regarding the public defense system in Idaho, this study engaged stakeholders whom the results may directly impact. In order to safeguard the integrity of this study, this was imperative as it gave attorneys agency and built trust for the policy-making process that may be impacted by the study’s results. Therefore, the engagement of and the contributions from Idaho attorneys in this study were both critical. Over 150 attorneys provided their insight, experience and expertise throughout the course of the project.

The detailed methodology outlined below was determined to be best suited to the state of Idaho, and the consequential resources and limitations, as well as the stated goals of the project: to provide Idaho-specific data for use in future efforts to set workload standards for the Idaho public defense system.

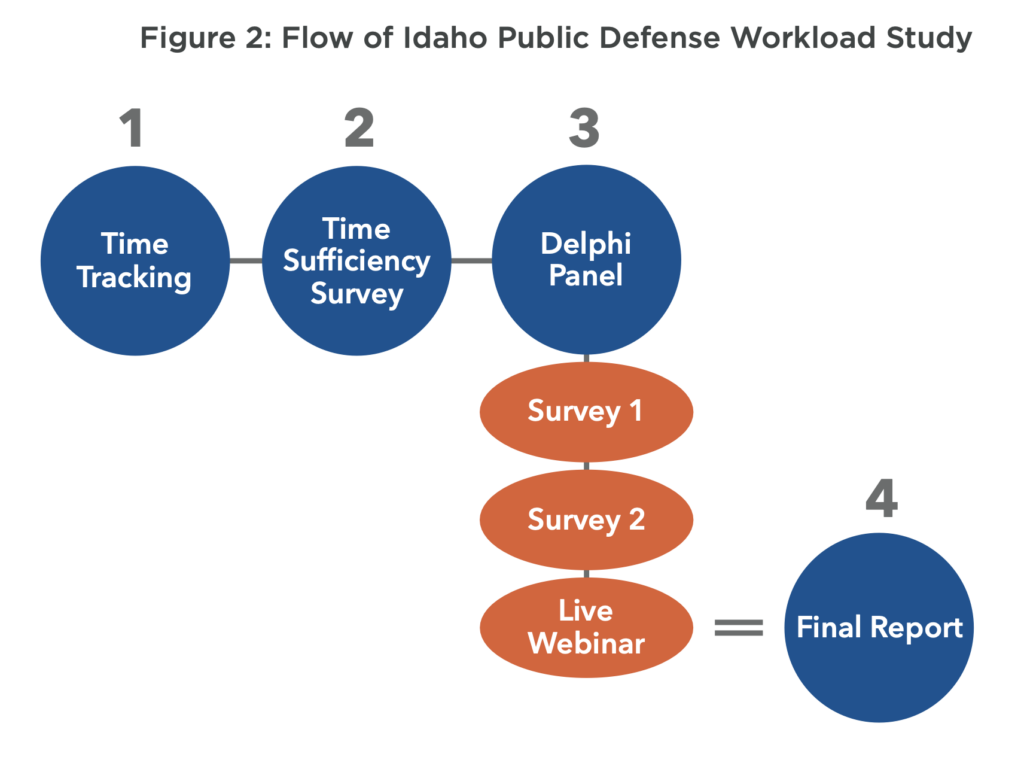

The study was divided into four main components, listed below and depicted in Figure 2:

- Time Tracking by public defense attorneys

- Time Sufficiency Survey of public defense attorneys

- Delphi Panel comprised of defense experts

- Final Report

Data Management

The aforementioned methodologies were each carried out and raw data was collected. After the raw data was collected it was cleaned before it was analyzed. Cleaning the data is a necessary part of the research process as it enables the research team to detect and correct or remove any corrupt or inaccurate (incomplete, incorrect, inaccurate, irrelevant) parts of the data. Since this research is human subjects research, cleaning the data before analysis also ensured that any identifying information of study respondents was removed, helping to reduce potential bias in the analysis. It is important to note; a release of any raw data runs the risk that the data will be misinterpreted and/or taken out of context and utilized to answer questions outside the scope of the study and to target study respondents. Therefore, IPI has taken great care in managing the data.

Once the data was collected it was stored in password-protected, cloud-based, server-backed, collection software. Once the raw data was extracted from the software it was stored on the cloud in a password protected, server-backed, shared drive only accessible by the research team.

Participant Protection and Privacy

It is of utmost importance in human subjects research to protect the privacy of those participating in a study. There were a number of protocols the IPI research team put in place for this particular research project. First, participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and they were also informed of the nature of the study and its purpose: to help provide Idaho-specific data that would be used to inform future public defense workload standards in Idaho. Participants consented to participate, and participants were permitted to drop out of the study for any reason, at any time.

To protect the privacy of study participants during data collection, participants were able to select where and when to participate in the web-based Time Tracking and survey portions of the study. This allowed them to enter data at work or at another location of their convenience. Because collection was done via web-based platforms, participants could enter data via a computer, tablet or smart phone.

As indicated in the Institutional Review Board applications for this study, the research team acknowledged certain risks to the participants including loss of confidentiality and identifiable links to individual participants. These risks were mitigated by only allowing the research team to have access to the raw data and, when applicable, de-identified raw data.

Conflicts of Interest

As indicated in the Institutional Review Board application and to the Office of Sponsored Research at Boise State University, none of the research team members on this project had any relationship or equity interest with any institutions or sponsors related to this research that might present or appear to present a conflict of interest with regard to the outcome of the research. IPI has a commitment to provide sound, objective research for Idaho decision makers. Therefore, all data collection, analysis, and presentation is done with the utmost integrity.

Definitions

Before addressing each of the three main components of the methodology it is important to provide definitions of words/phrases utilized in describing the methodology.

Case Types

The level of analysis used consistently throughout the study occurs at the “case” level. For this study, a “case” refers to a single indictment, although there could be more than one charge. Idaho defense attorneys participating in this study were asked to report and comment on a total of nine case types. The cases types were chosen with consideration for the legal landscape of Idaho.7 The case types included in this study (and their working definitions) are outlined in Appendix B.

Case Tasks

The time dedicated to a case was then broken down into specific case tasks. Like the Missouri study,8 this research was focused on tasks performed by attorneys themselves (as opposed to support staff that their office may retain)9 and thus the aspects of an attorney’s work life that are most affected by caseloads. Additionally, since caseload standards will affect the work of attorneys and the breadth of their workload, it is logical to focus on tasks performed regularly and [almost] exclusively by attorneys. The 17 case tasks, and their definitions, as used throughout this case study are outlined in Appendix C.10

Return to the beginning of the report

As mentioned, there were four main components to this study. The first three relate to the gathering and analysis of data and the final component is the presentation of the data in this report.

Part 1: Time Tracking

Time Tracking provided empirical data regarding the current public defense environment in Idaho workload related to specific case types. This data was then used to estimate the time spent on specific tasks as well as the overall length of time from intake to disposition for certain case types. Time Tracking is a tool that has been used in several other workload case studies11 and is an alternate way to gather information on the activity of attorneys, rather than relying on administrative data. Although administrative data from court systems and public defense offices offer accurate data for studies,12 studies utilizing only administrative data lack a powerful component that could later impact any enacted change: attorney participation. By asking attorneys to participate in Time Tracking, attorneys were encouraged to engage in the process of assessing their caseloads and work expectations. It is important to note that Time Tracking is a snapshot; it captures activity within a clearly defined window of time and cannot be assumed to represent how the public defense environment in Idaho is, every season of the year, year after year.

As stated, studies across the country have used a number of Time Tracking methodologies to establish the time attorneys spend on cases. This study used a 12-week Time Tracking period.13 For cases where intake and disposition happened within the study period the actual time on a case was calculated. Estimates on case length were made for cases where intake and/or disposition occurred outside the Time Tracking period.

This study sought to determine the average amount of time, from intake to disposition, spent on public defense cases in Idaho. Therefore, the research only engaged Idaho public defense attorneys as participants throughout the study.

Attorney Recruitment

Prior to this study, the PDC contacted attorneys throughout the state to inform them of the study and encourage participation in all aspects of the research. These contacts were made via letters sent via email to attorneys and during open meetings that the PDC held across the state. Before the Time Tracking component of the study began, the PDC contacted every public defense attorney in Idaho via email and requested their participation. The PDC also created a page14 on the PDC’s website to provide general information, answers to frequently asked questions, and the contact information of IPI so public defense attorneys, as well as the public as a whole, were informed of the study and knew how to contact the research team.

Once the study commenced, the IPI research team requested the PDC no longer be in one-on-one communication with Idaho public defense attorneys about the research project as such communication could unduly influence participation. However, the PDC did proceed to provide broadcast communication to attorneys to encourage participation. Additional encouragement for participation included a weekly drawing for legal text books. Attorneys who consistently tracked for all 12 weeks were entered into a drawing to win a trip to a public defense conference.

To recruit attorneys for each phase of the study, IPI utilized a Idaho public defense roster, provided by the PDC. At the time of the research, the roster contained a list of 290 attorneys.15 Although all attorneys were encouraged to participate in the study and utilize defenderData, some attorneys chose to use their own Time Tracking software while some opted out of the study.16

Attorneys who opted to use defenderData were provided with a login ID and a password by JusticeWorks. After logging in, the program presented attorneys with a form, requesting their consent to have their information recorded, which they were required to sign before entering any information. Attorney data was provided to IPI by JusticeWorks in the form of reports gleaned from defenderData.

Attorney Enrollment

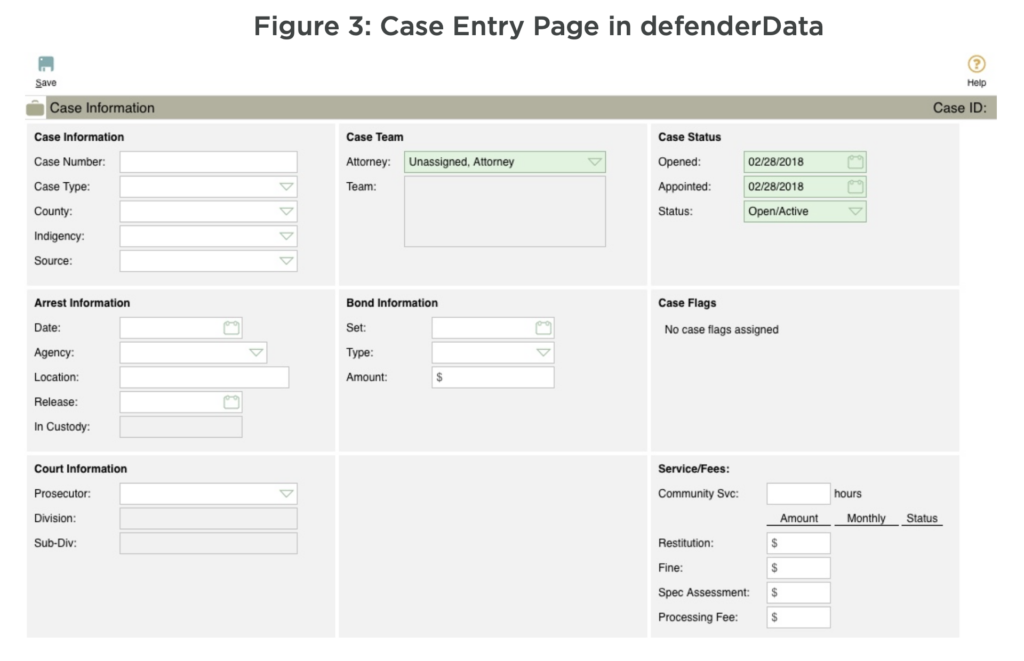

Email invitations were sent by IPI directly to attorneys to enroll them in the Time Tracking portion of the study. Prior to this study, most public defense attorneys did not consistently use a program to track the time they spent on cases. Therefore, in order to ensure consistency in collection of the data, it was determined that a software program would need to be provided to all of the state’s public defense attorneys. Attorneys were provided with free access to JusticeWorks’ defenderData software, a web-based, full-featured case management system designed and built exclusively for indigent defense and tailored specifically by JusticeWorks for use in Idaho. Table 1 shows the types of cases that were tracked and the task codes utilized when entering time spent on a case.

Table 1: Case Types and Case Tasks Codes for Time Tracking

| Case Types | Case Tasks | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| APP | Appeal | ADM | Administrative |

| BEC | Status Offenses (ARY/CHINS) | CC | Client Contact |

| CCV | Community Corrections Violation | CLR | Clerical |

| CHI | Child Rep Dependency | CT | Court |

| CMT | Civil Commitment/ITA | DD | Drafting Documents |

| CTO | Contempt – Other | DSC | Discovery |

| FEL | Felony | INV | Investigation |

| INF | Infraction | LR | Legal Research |

| JPV | Juvenile Probation Violation | LV | Leave |

| JVL | Juvenile | MG | Management |

| MIS | Misdemeanor | NG | Negotiation |

| NON | Non Charge Representation | SS | Social Services |

| OTR | Other | TP | Trial Prep |

| PAR | Parent Rep Dependency | TRN | Training |

| PRP | Personal Restraint Petition | TRV | Travel |

| PV | Probation Violation | CTPSC | Problem-Solving Court (InCourt) |

| SUP | Child Support Contempt | STPSC | Problem-Solving Court |

Data Collection

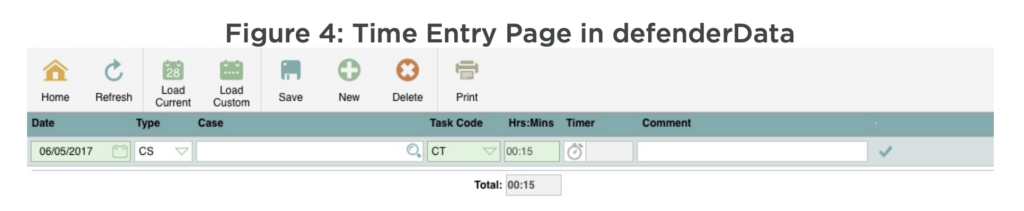

To prepare for data collection, attorneys using defenderData were asked to participate in a one hour training webinar. Two such webinars were held on March 30th, 2017, and April 4th, 2017. Each webinar was recorded and made available to attorneys who had been unable to participate live. These webinars included information about the defenderData program, including the login and data entry processes. Below, Figures 3 and 4 provide screen shots of the case entry and time entry features of the program. In addition, a user guide was created for attorneys and made available on the PDC website.

The Time Tracking section of the study took place in 2017, from April 24th to July 15th. During each week of Time Tracking, IPI received reports from JusticeWorks. If inconsistencies were detected in the data, IPI contacted the person who entered the data. After the 12 weeks of Time Tracking, JusticeWorks exported data for IPI. After cleaning the data, 10,170 eligible cases tracked by 138 attorneys representing 27 counties remained for use in calculating the descriptive statistics for use in the final workload study report.17,18

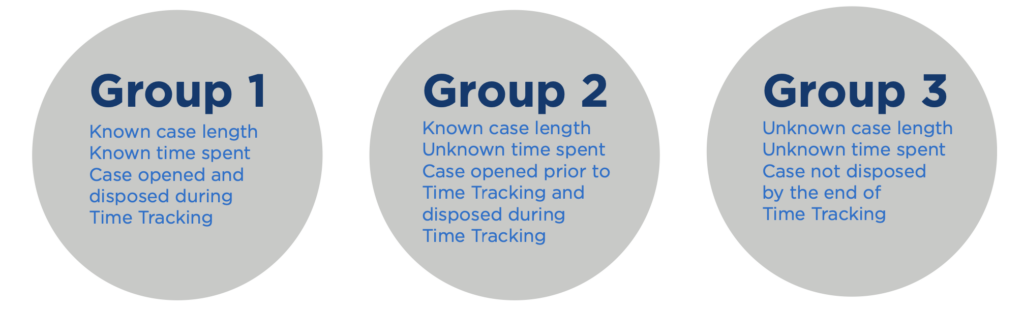

Group 1

Cases in this group were opened and disposed during the 12 weeks of Time Tracking.

Group 2

Cases in Group 2 opened before Time Tracking and were disposed during Time Tracking. Time for cases in Group 2 was estimated by first calculating the actual time spent each week on the case during Time Tracking. This number was then added to the average time spent each week during Time Tracking multiplied by the weeks the case was open outside of Time Tracking.

Group 3

Cases in Group 3 made up the vast majority of cases in Time Tracking. These were cases that were not disposed during Time Tracking. They could have been opened either before or during the study. Time for Group 3 was estimated by first calculating the actual time spent each week on the case during Time Tracking. This number was then added to the average time spent each week on the case during Time Tracking multiplied by the median weeks cases of the same type were open in Groups 1 and 2. However, if the time tracked on a case was longer than the median calculation, then the actual weeks outside of Time Tracking were used as the multiplier. This methodology was recommended by the Texas study which also tracked time for a 12-week period. If the average length of time public defense cases take to dispose in Idaho was available, that data could be used as the multiplier rather than the median. While the time would still an estimate, it would lead to a more precise estimate of averages times. Although that data was not available for calculation in this study, the Idaho Supreme Court is actively working to produce that data for the PDC.

Results and Analysis

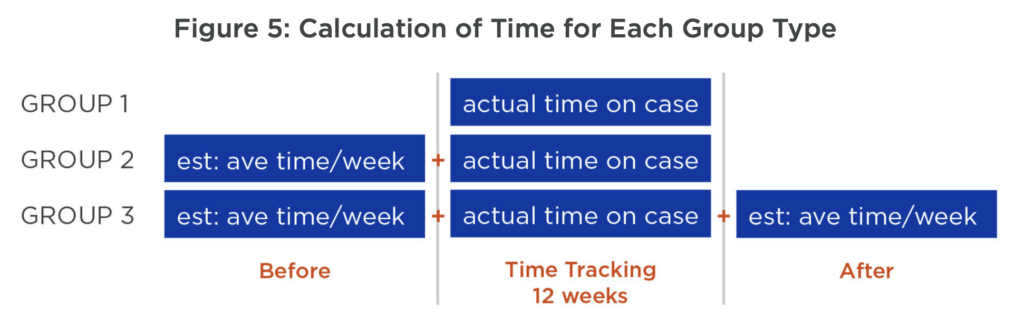

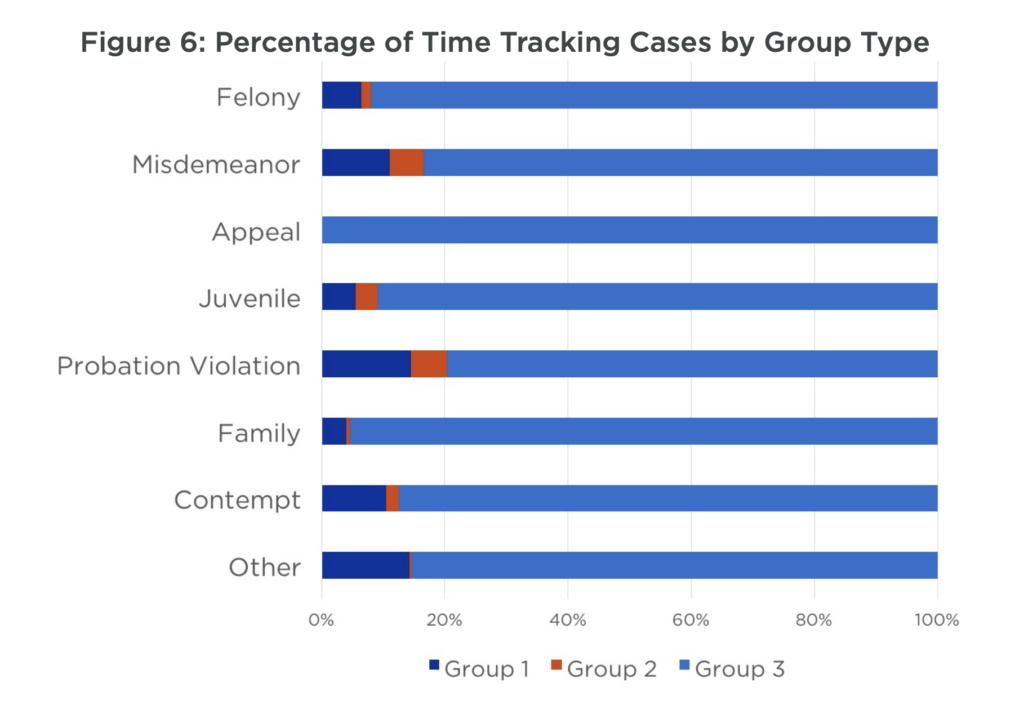

Each case was individually calculated based on their associated Group, as depicted in Figure 5, then descriptive statistics (distribution, central tendency, and dispersion) for each case type were calculated.

Figure 6 demonstrates the distribution of Groups for each case type. As mentioned, for each of the case types, Group 3 comprises the vast majority of cases.

Table 2 outlines the estimated average time in hours that each case type took to dispose according to the data analyzed from Time Tracking. Felonies and Misdemeanors made up the majority of cases tracked during Time Tracking, which is reflective of Idaho’s overall indigent defense case load. The standard deviation for each case type is also provided.

Table 2: Estimated Average Time per Case Type

| Case Type | Total Cases | Estimated Average Time to Complete Case (hrs) | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Felony | 3336 | 3.8 | 10.6 |

| Misdemeanor | 4213 | 2.2 | 10 |

| Appeal | 9 | * | * |

| Juvenile | 1118 | 2.6 | 7.7 |

| Probation Violation | 633 | 2.2 | 6.4 |

| Family | 546 | 3.4 | 8.2 |

| Contempt | 48 | 4 | 8.3 |

| Other | 267 | 2.8 | 6.4 |

*= Average time for appeal cases could not be calculated since only 9 appeal cases were recorded in Time Tracking and none of them were closed during the 12 week tracking period.

Time Tracking Limitations

Prior to this study, few public defense attorneys in Idaho were required to track how they spend their time on cases. Although training was provided for the Time Tracking portion of the study, one must recognize this was a new practice for attorneys, which may have limited their ability to accurately track their time.

A word of caution when interpreting the results: the aggregated data reported in this analysis present an overall average (mean) per case, as depicted in Figure 7. However, the mean alone does not provide enough information about the data. If the data were normally distributed and the distribution clustered around the mean, then presenting the mean in isolation would probably be sufficient.19 This data is not normally distributed or clustered around the mean, as indicated by another measure, standard deviation, which is necessary to fully interpret the story of the data. Standard deviation measures the dispersion of a set of data from its mean. The more spread apart the data, the higher the standard deviation. When there is a higher standard deviation relative to the mean one should also consult the range and distribution of data (see Appendix D).

To complement the quantitative results of the Time Tracking portion of the study, and better inform what was causing the large variation of time spent on cases within each case type, a survey was used to gather more qualitative information about public defense attorneys and their perceptions of time necessary for specific tasks and for different types of cases.

Return to the beginning of the report

Part 2: Time Sufficiency Survey

The Time Sufficiency Survey was used as a tool to gather both quantitative and qualitative data from public defense attorneys across Idaho. Previous studies from other states seeking to inform caseload standards surveyed defense attorneys to inquire how much time they perceived certain cases and tasks require for adequate defense to occur (See Appendix A – Bibliography). The Time Sufficiency Survey for this study was structured similarly to previous studies and acted as a way for attorneys to provide their insight on a number of matters: concepts of sufficient time, the availability of resources, and what effective counsel looks like in action.

The survey used in this project asked participating attorneys to select a numeric value for how much time, in their opinion, an attorney ought to spend on specific indigent defense case types in order to provide a client adequate and effective defense. The survey also asked attorneys to provide their perception of the average time required to complete specific tasks, if the task occurred, within certain case types. Attorneys were also provided an opportunity to explain their answers. This mixed methods approach adds great value to this research project as the survey connects the amount of time with the rationale of a practicing attorney who can provide valuable insight into their job and their experiences.

Attorney Recruitment and Enrollment

The Time Sufficiency Survey was sent via email to the entire roster20 of current Idaho defense attorneys. The survey was sent directly to the attorneys, which provided each attorney with a unique link to the survey. The email also served as informed consent; by linking to the survey, attorneys consented to participate.

Data Collection

The survey was created and distributed via Qualtrics, a web-based survey software program. The survey remained in the field for just over two weeks21 after which the raw data was exported for cleaning (a process described in Time Tracking above) and analysis in IBM’s SPSS, a statistical analysis software program. Attorneys were able to take the survey once, and they could choose to complete the survey either from a computer, smartphone, or tablet. The survey collected demographic information, attorneys’ perceptions about time spent on specific tasks and specific cases, and provided space for open-ended comments. The survey implemented a logic feature that enabled attorneys to only answer questions regarding the types of cases they currently handled as part of their regular workload. This logic was built in to direct attorneys to more accurately estimate the time required for cases most familiar to them.22 Therefore, only portions of the total number of participating attorneys provided estimates of time for each case type, as illustrated in Appendix E.

Results and Analysis

The response rate for the survey was 34%.23 Demographic information was collected to indicate if respondents were representative of Idaho public defense attorneys. Analysis of the survey results showed 97 attorneys participated in the survey, and represented 29 of Idaho’s 44 counties.24 On average, attorneys practiced defense law for 12 years (the minimum time recorded was 1 year and the maximum was 38 years) and when asked to estimate what percentage of their workload was dedicated to Indigent Defense Cases, on average of 93% of an attorneys workload was dedicated to Indigent Defense.25 Therefore, attorneys who chose to participate in this portion of the study had multiple years of experience practicing defense law and, at the time of the Time Sufficiency Survey, a significant portion of their workload was dedicated to indigent defense cases.

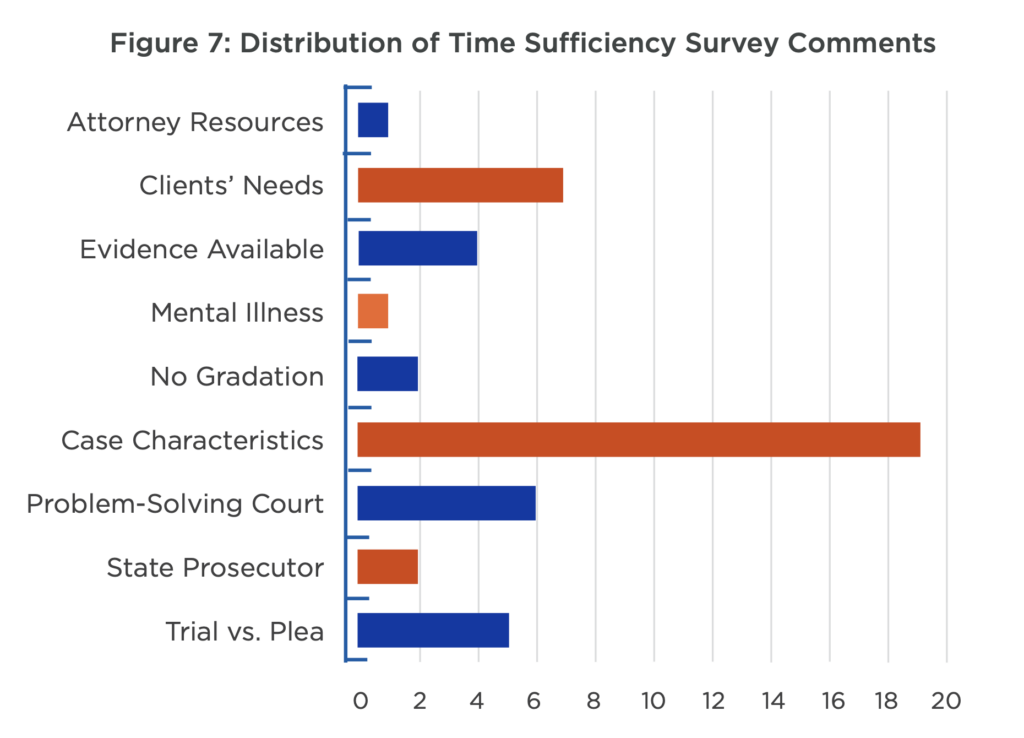

The Time Sufficiency Survey offered attorneys the opportunity to provide any additional comments they had regarding the survey through an open-ended comment box. During analysis, the comments made by the participating attorneys were reviewed and organized into reoccurring themes that described the content of comments and/or were specific points of reference for attorneys. Some comments addressed more than one theme and therefore were attributed to more than one theme. The comments were organized into these themes to analyze what are perceived to be the greatest issues and concerns for Idaho defense attorneys. The nine themes that the research team identified from the Time Sufficiency Survey comments are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3: Thematic Comments and Definitions

| Theme | Definition |

|---|---|

| Attorney Resources | The expertise and experience that an attorney has for a particular type of case and/or area of law. Additionally, the office resources available to an attorney and the extent of their travel. Whether an office is public or private has a bearing here. |

| Client Needs | The needs of a client which can be impacted by a variety of things. E.g. their cognitive capabilities, their emotional state, their physical state, and their demands. |

| Evidence Available | The amount of legitimate evidence involved in a case. |

| Mental Illness | The mental wellbeing / mental health of a client. |

| No Gradation | The lack of gradation amongst offense types within the same classification of a case. |

| Case Characteristics | The multitude of characteristics that form and impact an entire case / anything that contributes to the situating of a case. |

| Problem-solving Court | Interaction with Problem-solving Court during a case. |

| State Prosecutor | The prosecutor assigned to the case. |

| Trial vs. Plea | Whether a case goes to trial or not. |

A total of 40 attorneys chose to provide us with comments during the Time Sufficiency Survey. The table below shows the distribution of comment content across the nine identified themes.

After analysis of the Time Sufficiency Survey results, the research was finalized by assembling a panel of expert defense attorneys across Idaho.

Quotes from Time Sufficiency Survey Respondents

“Time required on a particular category of tasks seems to depend and vary widely based on the needs of a particular case”

“Law cases just don’t fit a template. Everyone is different with different demands and time needs”

“To try to represent a client properly it just takes as much time as it takes”

Return to the beginning of the report

Part 3: Delphi Panel

The Delphi method, developed by the RAND Corporation, is an iterative decision-making process that integrates the opinions of a group of very knowledgeable and respected experts within a certain field.26 The Delphi method has been used in several caseload studies across the US27 to guide experts through a process that gradually leads the participants to a consensus regarding the time that is needed to provide an adequate defense to clients, for each case type and case task.

The Delphi method designed for this project consisted of three stages: two online surveys distributed via Qualtrics, the web-based survey software program also utilized in the Time Sufficiency Survey, and one interactive group discussion session hosted via ZOOM, a cloud platform for video and audio conferencing, chat and webinars that can be accessed across mobile, desktop, laptop and room conferencing systems.28

Attorney Recruitment

In order to select a panel of defense experts for this study, IPI received lists of experienced public and private Idaho attorneys from the ACLU of Idaho and the Idaho Public Defense Commission. As a result, 62 attorneys were invited via email to participate as part of the Delphi Panel. The invited attorneys represented all judicial districts, both urban and rural counties, and provided a nearly equal mix of private and public defenders.

Delphi Round 1

The first stage of the Delphi process was an online survey. An email was sent to the Delphi panel members with a link to the survey. The email also served as informed consent for panelists, by clicking the link to the survey attorneys consented to participate in the entire Delphi process. Of the 62 attorneys invited to participate in Delphi Round 1, 16 attorneys responded.29

Similar to the Time Sufficiency Survey, the first Delphi survey asked for the input of the Delphi panel members on the time they perceived was needed to perform certain tasks, within certain case types (See definitions in Appendices B and C). The survey also asked Delphi members to estimate the percent of cases in which the task should occur. In order to provide qualitative data to support the quantitative data collected in the Time Sufficiency Survey, respondents were able to expand upon their time recommendations, add details to their responses, and offer any further comments they had regarding the survey via open ended comment sections.

Delphi Round 2

Again, 62 attorneys were invited to participate via email, and 15 attorneys responded to participate in Delphi Round 2.30 The second survey that was sent out to the Delphi panel members aggregated the results of the first Delphi survey and displayed the range of results, and the average response given for each question. Respondents were encouraged to review responses from Delphi Round 1 and then offer their re-estimations for time needed for each case task, within each case type. This process guided Delphi members to a consensus regarding time needed for case tasks.31 Tables 4 and 5 outline the results and the breakdown of responses to each case task within each case type from Time Sufficiency and Delphi Rounds 1 and 2 for Felonies and Misdemeanors. See Appendix F for a complete presentation of the remaining case types.

Table 4: Felony Case Task Averages

| Felony | Time Sufficiency | Delphi Round 1 | Delphi Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average perceived time required to complete task (hrs) | |||

| Negotiation | 2.43 | 1.41 | 1.29 |

| Social Services | 0.59 | 1.3 | 1.47 |

| Travel | 1.21 | 5.03 | 3.36 |

| Client Contact | 3.86 | 6.25 | 7.13 |

| Discovery | 3.37 | 4.15 | 4.32 |

| Administrative | 1.17 | 1.37 | 0.72 |

| Investigation | 2.97 | 5.65 | 6.86 |

| Legal Research | 9.05 | 7.1 | 8.93 |

| Trial Prep | 4.5 | 16.7 | 17.14 |

| Clerical | 1.13 | 2.25 | 2.36 |

| Court | 5.1 | 9.15 | 9.29 |

| Drafting Documents | 3.14 | 3.75 | 4.32 |

| Problem-Solving Court (in Court) | 4.5 | 17.4 | 12.7 |

| Problem-Solving Court (Staffing) | 4.41 | 12.6 | 18.7 |

Table 5: Misdemeanor Case Task Averages

| Misdemeanor | Time Sufciency | Delphi Round 1 | Delphi Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average perceived time required to complete task (hrs) | |||

| Negotiation | 1.12 | 0.91 | 0.75 |

| Social Services | 0.49 | 1.29 | 0.76 |

| Travel | 0.92 | 5 | 2 |

| Client Contact | 1.7 | 2.78 | 2 |

| Discovery | 1.37 | 2.11 | 1.5 |

| Administrative | 0.99 | 0.77 | 0.34 |

| Investigation | 1.25 | 2.67 | 2.1 |

| Legal Research | 1.23 | 2.03 | 1.9 |

| Trial Prep | 4.82 | 7.07 | 6 |

| Clerical | 0.79 | 1.17 | 1.2 |

| Court | 2.28 | 4.17 | 2.1 |

| Drafting Documents | 1.5 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Problem-Solving Court (in Court) | 0.93 | 21 | 13.5 |

| Problem-Solving Court (Staffing) | 0.79 | 39 | 18.25 |

Delphi Round 3

After the completion of Delphi Round 1 and Delphi Round 2, Delphi panelists were invited to an interactive online conference session that would allow deeper discussion into the answers that were recorded from both Delphi Rounds. Attorneys were asked to discuss the data from the Time Sufficiency Survey, and discuss differences, inconsistencies and themes in the data. The Delphi Panel also allowed attorneys the freedom to provide any feedback concerning the project as a whole, and or the larger legal environment in Idaho.

The Delphi Round 3 web conference was hosted through the online conference platform, ZOOM, and took place on Tuesday 29th August, MST 9am – 11am. Of the 62 attorneys invited to participate, 12 attorneys attended the call and provided their input. After the web conference was finished, first the conference recording was transcribed, and then the data was coded in a qualitative analysis software program, Nvivo. At the end of Delphi Round 3, there were 10 identified comment themes. The nine previously identified themes from the Time Sufficiency Survey and the addition of a new theme, State Appellate Court that arose during Delphi Rounds 2 and 3. Figure 8 depicts the overall thematic distribution of comments from Time Sufficiency and Delphi.

Results and Analysis

Table 4 provides a complete summary of the estimated total time necessary to dispose cases from each round of the study.

Table 4: Summary of Estimated Total Case Time

| Summary of Estimated Time by Case Type | Time Tracking Study | Time Sufficiency Survey | Time Sufficiency Survey | Delphi Round 1 | Delphi Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average time needed to complete entire case (hrs) | Average time needed to complete entire case (hrs) | Total time needed to complete case when all task averages are compiled (hrs) | |||

| Felony | 3.8 | 14.77 | 38.52 | 64.11 | 67.19 |

| Misdemeanor | 2.2 | 5.42 | 18.46 | 31.97 | 21.95 |

| Appeal | * | 25.02 | 34.96 | 48.05 | 46.81 |

| Juvenile | 2.6 | 3.72 | 14.06 | 24.7 | 17.47 |

| Family | 3.4 | 11.74 | 23.79 | 23.75 | 27.41 |

| Contempt | 4 | 3.48 | 11.32 | 17.42 | 15.53 |

| Other | 2.8 | 3.46 | 10.39 | 11.25 | 9.67 |

| Probation Violation | 2.2 | 3.6 | 13.11 | 13.77 | 10.37 |

*= Not all tasks occur in 100% of cases, therefore these numbers likely represent an overestimate of time

As Table 4 demonstrates, there is a wide range in perceived time cases require. As discussed previously, the ranges in recorded time for each case type during Time Tracking was considerable. There are a number of possible reasons for these variations as discussed below.

Time Sufficiency and Delphi Panel Limitations

The participants in the Delphi Panel were expert defense attorneys. A Delphi-type panel analysis is designed to inform specific sets of recommendations rather than just aggregating data. As with any other analysis with small, non-representative samples, it can be prone to outliers, meaning that one or two respondents can affect the averages in ways that may not represent the entire panel. Therefore, the focus of the data from the Delphi panel should be on the qualitative data rather than the aggregated reports. For example, the Delphi panel was comprised of expert public defenders. As such, they are more experienced attorneys who may be handling more complex, and time-consuming cases than the average Idaho public defense attorney and, thus, their perception of time needed for specific cases and specific tasks may be impacted.

The Delphi process did not ask participants to estimate total time necessary to dispose cases; attorneys were requested to estimate the necessary time of each task and percentage of cases those tasks occur. It was anticipated that overall time required for cases would be discussed in detail during Delphi Round 3. However, during Round 3 attorneys tended to focus in on specific tasks. Therefore, the only calculation provided for total required time for cases from the Delphi process is a sum of the average estimated time of each task for each case type. Since all cases do not include all tasks this is most likely an overestimate of total time perceived necessary for each case type.

For the Time Sufficiency Survey and Delphi Panel portions of the study it is important to note issues associated with recalling time spent, which attorneys most likely did to inform their responses. In each of these components of the study, attorneys were asked to use their past experiences to recall the average amount of time an attorney should spend on specific cases and specific tasks, thus providing an estimate. Previous research has indicated that when people are asked to estimate time dedicated to activities, they tend to overestimate.32,33,34 Attorneys’ work is not always conducive to the linear flow of time and, in fact, their work tasks are often overlapping, intertwined and crisscrossing in nature, which offers an additional complication to the collection of recollection of time.35

Finally, participation in this study was voluntary. Therefore, the resulting data collected may be impacted by selection bias of the respondents. This bias may include unwillingness to participate due to a perception that engagement in the study would take too much effort, a lack of understanding of the context of the study, or an unwillingness to share sensitive information.

Return to the beginning of the report

1 U.S. Constitution amend. VI, U.S. Constitution amend. XIV.

2 Magistrate judges assign the vast majority of Idaho’s public defense cases to the state’s public defense attorneys. These attorneys may be part of a countywide office, may be a contract attorney for counties without an office, or may be a conflict attorney. Conflict attorneys handled cases where contract or in-house attorneys have a conflict of interest.

3 Brown, Rubin. (2014). The Missouri Project: A study of the Missouri Public Defender System and Attorney Workload Standards. Carmichael, D., Clemens, A., Marchbanks, III, M., P., & Wood, S. (2015). Guidelines for Indigent Defense Caseloads: A report to the Texas Indigent Defense Commission. Public Policy Research Institute, Texas A&M University. Labriola, M., Farley, E. J., Rempel, M., Raine, V., & Martin, M. (2015). Indigent defense reforms in Brooklyn, New York: An analysis of mandatory case caps and attorney workload. New York: Center for Court Innovations. Luchansky, B. (2010). The Public Defense Pilot Projects Washington State Office of Public Defense. Olympia, WA: Looking Glass Analytics. Postlethwaite & Netterville. (2017). The Louisiana Project: A study of the Louisiana Public Defender System and Attorney Workload Standards. The American Bar Association.

4 Adams County, Bear Lake County, Benewah County, Bingham County, Blaine County, Boise County, Boundary County, Butte County, Camas County, Caribou County, Clark County, Clearwater County, Custer County, Elmore County, Franklin County, Fremont County, Gem County, Idaho County, Jefferson County, Jerome County, Latah County, Lemhi County, Lewis County, Lincoln County, Madison County, Nez Perce County, Owyhee County, Payette County, Shoshone County, Teton County, Valley County, and Washington County

5 Of these twelve counties eight have independent institutional offices (Ada, Bannock, Bonner, Bonneville, Canyon, Gooding, Kootenai and Twin Falls) while four have joint institutional offices (Minidoka and Cassia Counties share an institutional office and Power and Oneida Counties share an institutional office).

6 Idaho Code 19-864 requires all defending attorneys to submit an annual report by November 1 of each year to the board of county commissioners, the corresponding administrative district judge and the PDC.

7 The research team collaborated with the PDC and Justice Works select the case types based on recommendations and the limitations of the software employed for this study.

8 Brown, Rubin. (2014). The Missouri Project: A study of the Missouri Public Defender System and Attorney Workload Standards.

9 Not all Idaho indigent defense attorneys operate out of a county office that retains support staff. There were a number of conflict attorneys and contract attorneys participating in this study who have no access to support staff. Any contribution that support staff might have to an attorney’s workload was accounted for by asking Idaho indigent defense attorneys to detail any additional support they had access to (this information was gathered during the Time Sufficiency Survey).

10 The case tasks chosen for the purpose of this study were shaped by both the legal landscape of Idaho and council from the PDC and Justice Works.

11 Brown, Rubin. (2014). The Missouri Project: A study of the Missouri Public Defender System and Attorney Workload Standards. Carmichael, D., Clemens, A., Marchbanks, III, M., P., & Wood, S. (2015). Guidelines for Indigent Defense Caseloads: A report to the Texas Indigent Defense Commission. Public Policy Research Institute, Texas A&M University. Labriola, M., Farley, E. J., Rempel, M., Raine, V., & Martin, M. (2015). Indigent defense reforms in Brooklyn, New York: An analysis of mandatory case caps and attorney workload. New York: Center for Court Innovations. Luchansky, B. (2010). The Public Defense Pilot Projects Washington State Office of Public Defense. Olympia, WA: Looking Glass Analytics. Postlethwaite & Netterville. (2017). The Louisiana Project: A study of the Louisiana Public Defender System and Attorney Workload Standards. The American Bar Association.

12 Labriola, M., Farley, E. J., Rempel, M., Raine, V., & Martin, M. (2015). Indigent defense reforms in Brooklyn, New York: An analysis of mandatory case caps and attorney workload. New York: Center for Court Innovations.

13 Due to the constraints of this study, 12 weeks was selected as an appropriate length for Time Tracking. Other studies with similar constraints tracked time for 12 weeks, see: Carmichael, D., Clemens, A., Marchbanks, III, M., P., & Wood, S. (2015). Guidelines for Indigent Defense Caseloads: A report to the Texas Indigent Defense Commission. Public Policy Research Institute, Texas A&M University.

14 https://pdc.idaho.gov/idaho-workload-study/

16 Half of the attorneys in Ada County’s office selected to participate in the study and were contacted by IPI. All of Canyon County’s public defenders utilized the county’s in-house software. An additional 11 attorneys selected to utilize their own time tracking methodology. However, due inconsistencies in tracking time and reporting, the Time Tracking data collected outside of defenderData was unable to be utilized in the study.

17 In some instances attorneys represented clients from more than one county.

18 Cases were eliminated if they: had <= 0 hours entered from 4/24/2017-7/15/2017, if closed dates were prior to 4/24/2017, if appointed dates were after closed dates (resulting in a case being open <0 days), or if they were inactive,

19 Measures of central tendency (arithmetic mean, median, mode, standard deviation, etc.) are important tools for presenting data in an aggregated form. Together, measures of central tendency present a wellrounded picture of the data. However, when used in isolation, those same measures can distort the data and provide information that can be misleading. This report relies primarily on two measures: (1) mean, and (2) standard deviation.

20 At the time of the survey, 290 attorneys were on the public defense roster. Although all attorneys surveyed provided indigent defense, some also provided private defense. This was due to the nature of Idaho’s Public Defense system, which utilizes contract and conflict attorneys, in addition to salaried defense attorneys in institutional offices.

21 The Time Sufficiency Survey was in the field from August 1st, 2017 until August 16th, 2017. During the time that the survey was in the field, IPI sent three email reminders to attorneys to encourage their participation. On August 11th, the PDC sent an email to attorneys to remind attorneys of the active survey and to encourage their participation.

22 Accuracy to recall time spent on a task is reduced the further in the past a task occurred.

23 A total of 298 emails were sent. 6 emails were duplicates and 6 emails bounced. This reduced our sample population to 286. 2 attorneys formally declined to participate, 27 attorneys only provided partial responses, and 2 attorneys started the survey and did not proceed: these responses were therefore excluded from data analysis to preserve the validity of the analysis. This resulted in 97 usable responses for analysis. We therefore had a response rate of 34%.

24 Counties represented in the Time Sufficiency Survey include: Ada, Bannock, Caribou, Bonner, Boundary, Kootenai, Butte, Bonnerville, Camas, Jefferson, Canyon, Cassia, Clearwater, Elmore, Gem, Gooding, Idaho, Jerome, Latah, Lewis, Nex Perce, Owyhee, Payette, Washington, Shoshone, Teton, Twin Falls, Valley, Washington, and one respondents did not indicate their county affiliation.

25 The minimum was 5 percent, and the maximum was 100 percentage. The standard deviation was 18.49.

26 Adler, M., & Ziglio, E. (Eds.). (1996). Gazing into the oracle: the Delphi method and its application to social policy and public health. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

27 Labriola, M., Farley, E. J., Rempel, M., Raine, V., & Martin, M. (2015). Indigent defense reforms in Brooklyn, New York: An analysis of mandatory case caps and attorney workload. New York: Center for Court Innovations

28 Other workload studies implementing the Delphi method hosted an in-person meeting for the final group discussion. An online live discussion was chosen for the Idaho study due to time (length of study and availability of attorneys) and financial constraints.

29 5 responses were partial and immediately excluded from analysis. Additionally, it is important to note that of the remaining 11 responses, not every participating attorney provided responses to every question for analysis but attorneys did progress through the entire survey (and therefore not excluded as a ‘partial’ response).

30 1 attorney opted out of the survey and was therefore excluded from analysis. An additional 5 attorneys only provided partial response and were therefore excluded from analysis. A total of 9 attorney responses were viable and used for analysis.

31 The guidance offered in the Delphi method minimizes bias from outside the panel because the information used for guidance is generated by the Delphi members themselves. This iterative process allows for the interaction of experts to produce results that are well-rooted within the community and legal environment of Idaho.

32 Pentland, W. E., Lawton, M. P., Harvey, A. S., & McColl, M. A. (Eds.). (2002). Time use research in the social sciences. Boston: Springer.

33 Although breaking down the workweek in to specific tasks (microbehaviors) has been beneficial in some studies (see Pentland, W. E., Lawton, M. P., Harvey, A. S., & McColl, M. A. (Eds.). (2002). Time use research in the social sciences. Boston: Springer: p. 58), other studies have indicated that by doing so, the accumulation of tasks has led to workers reporting work weeks of over 168 hours (see Robinson, J. P., Martin, S., Glorieux, I., & Minnen, J. (2011). The overestimated workweek revisited. Monthly Labor Review, 134(6)).

34 Participants are also more inclined to give “socially desirable responses” (Robinson, J. P., Martin, S., Glorieux, I., & Minnen, J. (2011). The overestimated workweek revisited. Monthly Labor Review, 134(6): p. 45). Meaning, that participants are aware of the social implications of how they record their time. Inferring an awareness of participants to the social, political and economic environment in which they are operating (reporting). This bias must be considered.

35 Stinson, L.L. (1999). Measuring how people spend their time: a time-use survey design. Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Monthly Labor Review, 122(8).

Return to the beginning of the report

Adler, M., & Ziglio, E. (Eds.). (1996). Gazing into the oracle: the Delphi method and its application to social policy and public health. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Beeman, M. (2012). Using Data to Sustain and Improve Public Defense Programs. Chicago: American Bar Association Standing Committee on Legal Aid and Indigent Defendants.

Beeman, M. (2014). Basic data every defender program needs to track: A toolkit for defender leaders. Washington, DC: National Legal Aid & Defender Association.

Brown, R. (2014). The Missouri Project: A study of the Missouri Public Defender System and Attorney Workload Standards.

Burkhart, G. T. (2017). How to leverage public defense workload studies. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 14(2), 403-429.

Carmichael, D., Clemens, A., Marchbanks, III, M., P., & Wood, S. (2015). Guidelines for Indigent Defense Caseloads: A report to the Texas Indigent Defense Commission. Public Policy Research Institute, Texas A&M University.

Child Protective Act, 16 Idaho § 1602-10 (1976).

Dalkey, N., & Helmer, O. (1962). An experimental application of the Delphi Method to the use of experts. Santa Monica, CA: The Rand Corporation.

Davies, A.L.B., & Morre, J. (2017). Critical issues and new empirical research in public defense: An introduction. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 14(2), 337-344.

Gordon, T. J. (1994). The Delphi method. Futures Research Methodology, 2.

Harvey, A. (1993). Guidelines for time use data collection. Social Indicators Research, 30, 197–228.

Hsu, C.-C., & Sandford, B. A. (2007). The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 12(10), 1–8.

Idaho Public Defense Commission. (2018). Idaho Workload Study. Retrieved from https://pdc.idaho.gov/idaho-workload-study/

Judicial Branch, State of Idaho. (2015). 2015 annual report: Idaho judiciary. Retrieved from https://isc.idaho.gov/annuals/2015/2015-Annual-Report.pdf

Labriola, M., Farley, E. J., Rempel, M., Raine, V., & Martin, M. (2015). Indigent defense reforms in Brooklyn, New York: An analysis of mandatory case caps and attorney workload. New York: Center for Court Innovations.

Laurin, J.E. (2016). Data and accountability in indigent defense. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 14(2), 373-402. Retrieved from https://kb.osu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/1811/80801/OSJCL_V14N2_373.pdf

Lefstein, N. (2009). Eight guidelines of public defense related to excessive workloads. Chicago: American Bar Association Standing Committee on Legal Aid and Indigent Defendants.

Lefstein, N. (2011). Securing reasonable caseloads: Ethics and law in public defense. Chicago: American Bar Association Standing Committee on Legal Aid and Indigent Defendants. Retrieved from http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/books/ls_sclaid_def_s ecuring_reasonable_caseloads.pdf

Linstone, H. A., & Turoff, M. (1975). The Delphi method. Addison-Wesley Reading, MA.

Lorelei, L. (2017). Starved of money for too long, public defender offices are suing – and starting to win. American Bar Association Journal. Retrieved from http://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/the_gideon_revolution.

Luchansky, B. (2010). The Public Defense Pilot Projects Washington State Office of Public Defense. Olympia, WA: Looking Glass Analytics.

Erwin, M., & Ledyard, M. (2016). Increasing Analytics Capacity: a toolkit for Public Defender Organizations. Washington, DC: National Legal Aid & Defender Association.

Michigan Indigent Defense Commission. (2017). Request for proposals: Michigan public defense caseload standards study. Retrieved from http://michiganidc.gov/wpcontent/uploads/2017/03/MIDC-Caseload-RFP.pdf

National Association for Public Defense. (2015, March 19). NAPD statement on the necessity of meaningful workload standards for public defense delivery systems. Retrieved from http://www.publicdefenders.us/files/NAPD_workload_statement.pdf

National Legal Aid & Defender Association. (2013). Toolkit: Building In-House Research Capacity. Retrieved from http://www.nlada.org/sites/default/files/pictures/NLADA_ToolkitResearch_Capacity.pdf

National Legal Aid & Defender Association (NLADA). (2010). The Guarantee of Counsel: Advocacy and Due Process in Idaho’s Trial Courts.

National Legal Aid and Defender Association. (2007, August 24). American Council of Chief Defenders Statement on Caseloads and Workloads. Retrieved from https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_aid_indigent_ defendants/ls_sclaid_def_train_caseloads_standards_ethics_opinions_combined.aut hcheckdam.pdf

Neeley, E. (2008). Lancaster County Public Defender Workload Assessment. Public Policy Center, University of Nebraska.

North Carolina Office of Indigent Defense Services. (2014). Open Society Foundations Final Grant Report.

Office of State Public Defender, Mississippi. (2016). Assessment of Caseloads in State and Local Indigent Defense Systems in Mississippi.

Pentland, W. E., Lawton, M. P., Harvey, A. S., & McColl, M. A. (Eds.). (2002). Time use research in the social sciences. Boston: Springer. Retrieved from //www.springer.com/us/book/9780306459511

Postlethwaite & Netterville. (2017). The Louisiana Project: A study of the Louisiana Public Defender System and Attorney Workload Standards. The American Bar Association.

Robinson, J. P., Martin, S., Glorieux, I., & Minnen, J. (2011). The overestimated workweek revisited. Monthly Labor Review, 134(6).

Stinson, L.L. (1999). Measuring how people spend their time: a time-use survey design. Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Monthly Labor Review, 122(8).

The International Legal Foundation. (2016). Measuring Justice: defining and evaluating quality for criminal legal aid providers.

The Spangenberg Group & the Center for Justice, Law and Society at George Mason University. (2009). Assessment of the Washoe and Clark County, Nevada. Public Defender Offices, Final Report.

User Guide to the ILS Caseloads Standards Timekeeping Application. (n.d.). New York State Office of Indigent Legal Services.

Return to the beginning of the report

Appendix B: Case Types and Definitions

| Case Type Name | Including | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Felony | Representing an individual in a criminal case where possible imprisonment exceeds 1 year. | |

| Misdemeanor | Representing a minor wrongdoing. An individual in a criminal case where possible confinement is 1 year or less. | |

| Appeal | Seeking review of a decision from a higher court. | |

| Juvenile | Representing a child* charged with a criminal law violation. | |

| Juvenile | Juvenile Probation Violation | Representing a child accused of violating their terms of violation. |

| Status Ofense | Representing a child in a “child in need of supervision” case. | |

| Probation Violation | Representing an individual accused of violating their terms of violation. | |

| Child Rep. Dependency | Representing a child in a civil action related to that child. | |

| Family | Parent Rep. Dependency | Representing a parent in a civil action related to a child. |

| Child Support Contempt | Representing an individual charged with contempt in court relating to a failure to pay child support. | |

| Contempt | Representing an individual held in contempt of court. | |

| Other | Other | Cases that do not fit into the other defined categories. |

| Civil Commitment | Representing an individual in a case seeking to confine the individual civilly. | |

| Infraction | Representing an individual in a criminal case where no sentence of incarceration is possible. | |

| Non-charge Representation | Representing an individual who has not been charged with a criminal or civil law violation. |

*In accordance with Idaho law (Idaho Statute 16-1602-10), a child is an individual under the age of 18.

Return to the beginning of the report

Appendix C: Case Tasks and Definitions

| Case Task Name | Definition |

|---|---|

| Administrative | Conducting tasks necessary for running an office. E.g. time keeping, billing, and docket management tasks. |

| Client Contact | Communicating (consulting and interviewing) with clients, in-person, on the phone or via written correspondence. |

| Clerical | Processing non case-related or non case-specific paperwork. |

| Court | Time spent in court. |

| Drafting Documents | Attorney time dedicated to actually drafting, typing, or reviewing legal documents including motions and briefs. |

| Discovery | Time spent processing prosecution’s disclosure, requesting, acquiring and reviewing records. |

| Investigation | Time spent investigating facts/preparing for and conducting depositions or witness interviews/consulting any experts including testimony preparation. |

| Legal Research | Case related legal research for arguments, motions or briefs/research into alternative sentencing resources, e.g., treatment programs. |

| Leave | Vacation time/sick time. |

| Management | Time spent by chief defenders managing attorneys or attorneys managing staff. |

| Negotiation | Time spent communicating, meeting and negotiating with prosecutors. |

| Social Services | Time spent seeking assistance from social services or communicating with a social worker. |

| Training | Time spent in continuing legal education. |

| Travel | Traveling from office to courthouse or to meet with clients/witnesses. |

| Trial Prep | Preparing for trial. Reviewing potential objections of foundation for evidence. |

| Problem-Solving Court (in court) | Time spent in problem-solving court. |

| Problem-Solving Court (staffing) | Time spent staffing in a problem-solving court. |

Return to the beginning of the report

Felony

| Time (hours) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Range | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | |

| 3336 | 0.02 | 304.91 | 304.89 | 3.7681 | 1.83 | 10.63906 | |

| Group 1 | 216 | 0.08 | 92 | 91.92 | 2.58 | 1.6 | 7.02 |

| Group 2 | 53 | 0.08 | 105.34 | 105.27 | 6.48 | 2.52 | 15.7 |

| Group 3 | 3067 | 0.02 | 304.91 | 304.89 | 3.8 | 185 | 10.74 |

Misdemeanor

| Time (hours) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Range | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | |

| 4213 | 0.02 | 475.88 | 475.88 | 2.188 | 0.9333 | 10.00322 | |

| Group 1 | 466 | 0.08 | 28.21 | 28.13 | 1.15 | 0.6 | 2.11177 |

| Group 2 | 229 | 0.03 | 475.88 | 475.84 | 10.7 | 1.8 | 40.22271 |

| Group 3 | 3518 | 0.02 | 50.4 | 50.38 | 1.77 | 0.97 | 3.05 |

Appeal – N/A not enough data

Juvenile

| Time (hours) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Range | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | |

| 1116* | 0.02 | 210.22 | 210.2 | 2.6219 | 1.3265 | 7.69247 | |

| Group 1 | 61 | 0.03 | 6.5 | 6.47 | 1.38 | 0.92 | 1.39834 |

| Group 2 | 41 | 0.03 | 63.9 | 63.87 | 7.16 | 1.47 | 14.76555 |

| Group 3 | 1014 | 0.02 | 210.22 | 210.2 | 2.51 | 1.35 | 7.44784 |

*= 2 missing

Probation Violation

| Time (hours) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Range | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | |

| 633 | 0.02 | 98.08 | 98.05 | 2.1768 | 0.9536 | 6.35192 | |

| Group 1 | 92 | 0.08 | 6.75 | 6.67 | 1.06 | 0.66 | 1.13168 |

| Group 2 | 37 | 0.14 | 82.08 | 81.94 | 5.21 | 1.58 | 13.92842 |

| Group 3 | 504 | 0.02 | 98.08 | 98.05 | 2.16 | 0.97 | 5.97322 |

Family

| Time (hours) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Range | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | |

| 546 | 0.07 | 114.51 | 114.44 | 3.4498 | 1.5057 | 8.233 | |

| Group 1 | 22 | 0.5 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 1.66 | 1.15 | 1.46254 |

| Group 2 | 3 | 0.69 | 61.32 | 60.63 | 22.3 | 4.9 | 33.85619 |

| Group 3 | 521 | 0.07 | 114.51 | 114.44 | 3.42 | 1.53 | 8.02237 |

Contempt

| Time (hours) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Range | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | |

| 48 | 0.1 | 37.7 | 37.6 | 3.9882 | 0.665 | 8.26065 | |

| Group 1 | 5 | 0.36 | 2 | 1.64 | 1 | 0.83 | 0.6668 |

| Group 2 | 1 | 20.62 | 20.62 | 0 | 20.62 | 20.62 | n/a |

| Group 3 | 42 | 0.1 | 37.7 | 37.6 | 3.95 | 0.5 | 8.38699 |

Other

| Time (hours) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Range | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | |

| 267 | 0.03 | 75.5 | 75.52 | 2.7515 | 1.08 | 6.43562 | |

| Group 1 | 38 | 0.03 | 6 | 5.97 | 1.19 | 0.59 | 1.53735 |

| Group 2 | 1 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0 | 0.4114 | 0.4114 | n/a |

| Group 3 | 228 | 0.08 | 75.55 | 75.47 | 3.02 | 1.2 | 6.90228 |

Return to the beginning of the report

Time Sufficiency Survey Attorney Expertise by Case Type

| Case Type | Felony | Misdemeanor | Appeal | Juvenile | Probation Violations | Family | Contempt | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Attorneys | 70 | 61 | 23 | 26 | 80 | 28 | 34 | 27 |

| Percentage of Total N | 72.16% | 62.89% | 23.71% | 26.80% | 82.47% | 28.87% | 35.05% | 27.84% |

| Total N: 97 |

Return to the beginning of the report

Case Task Averages: Appeals

| Appeal | Time Sufficiency | Delphi Round 1 | Delphi Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average perceived time required to complete task (hrs) | |||

| Negotiation | 0.28 | 1 | 1 |

| Social Services | 0.12 | 0 | 0 |

| Travel | 0.62 | 5.28 | 4.3 |

| Client Contact | 1.46 | 1.88 | 1.38 |

| Discovery | 4.37 | 6.6 | 5.6 |

| Administrative | 1.82 | 1.79 | 0.95 |

| Investigation | 2.03 | 5.33 | 3.2 |

| Legal Research | 8.18 | 9.83 | 11.4 |

| Trial Prep | 2.47 | 2.5 | 2.63 |

| Clerical | 0.99 | 1.63 | 1.3 |

| Court | 1.37 | 1.21 | 1.25 |

| Drafting Documents | 11.26 | 11 | 13.8 |

Case Task Averages: Juvenile

| Juvenile | Time Sufficiency | Delphi Round 1 | Delphi Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average perceived time required to complete task (hrs) | |||

| Negotiation | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.65 |

| Social Services | 0.67 | 1.36 | 1 |

| Travel | 0.82 | 1.3 | 0.77 |

| Client Contact | 1.74 | 2.43 | 1.98 |

| Discovery | 1.03 | 2.17 | 1.36 |

| Administrative | 0.64 | 0.91 | 0.3 |

| Investigation | 1.08 | 1.71 | 1.4 |

| Legal Research | 1.09 | 2.71 | 1.8 |

| Trial Prep | 2.66 | 5.53 | 3.7 |

| Clerical | 0.8 | 1.29 | 1.21 |

| Court | 1.71 | 2.36 | 2.2 |

| Drafting Documents | 0.98 | 2 | 1.1 |

Case Task Averages: Probation Violation

| Probation Violation | Time Sufficiency | Delphi Round 1 | Delphi Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average perceived time required to complete task (hrs) | |||

| Negotiation | 1.02 | 0.8 | 0.63 |

| Social Services | 0.48 | 1.13 | 0.95 |

| Travel | 0.69 | 1.19 | 0.88 |

| Client Contact | 2.08 | 1.84 | 0.95 |

| Discovery | 1.21 | 1.03 | 0.83 |

| Administrative | 1.13 | 0.65 | 0.37 |

| Investigation | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| Legal Research | 0.89 | 1.11 | 1.1 |

| Trial Prep | 1.04 | 1.25 | 1.08 |

| Clerical | 0.57 | 0.89 | 0.43 |

| Court | 2 | 1.69 | 1.37 |

| Drafting Documents | 1.11 | 1.28 | 0.9 |

Case Task Averages: Family

| Family | Time Sufficiency | Delphi Round 1 | Delphi Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average perceived time required to complete task (hrs) | |||

| Negotiation | 1.08 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| Social Services | 1.19 | 2 | 1.63 |

| Travel | 0.97 | 0.8 | 1 |

| Client Contact | 3.73 | 3.75 | 5.5 |

| Discovery | 2.26 | 3.3 | 3.63 |

| Administrative | 1.1 | 0.56 | 0.38 |

| Investigation | 1.4 | 1.13 | 1.05 |

| Legal Research | 1.12 | 1.33 | 1.33 |

| Trial Prep | 3.76 | 2.25 | 4.13 |

| Clerical | 1.23 | 1.05 | 1 |

| Court | 4.37 | 3 | 3.63 |

| Drafting Documents | 1.58 | 3.3 | 2.88 |

Case Task Averages: Contempt

| Contempt | Time Sufficiency | Delphi Round 1 | Delphi Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average perceived time required to complete task (hrs) | |||

| Negotiation | 0.79 | 1 | 1 |

| Social Services | 0.53 | 0.25 | 0.4 |

| Travel | 0.61 | 0.5 | 0.75 |

| Client Contact | 1.26 | 2 | 2.13 |

| Discovery | 0.91 | 1 | 1 |

| Administration | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.3 |

| Investigation | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Legal Research | 0.67 | 1.17 | 1.13 |

| Trial Prep | 2.43 | 5.67 | 3.63 |

| Clerical | 0.68 | 1 | 0.81 |

| Court | 1.25 | 2 | 2.38 |

| Drafting Documents | 0.87 | 1.33 | 1.25 |

Case Task Averages: Other

| Other | Time Sufficiency | Delphi Round 1 | Delphi Round 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average perceived time required to complete task (hrs) | |||

| Negotiation | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.61 |

| Social Services | 0.59 | 0.25 | 0.77 |

| Travel | 0.69 | 1.25 | 0.88 |

| Client Contact | 1.31 | 1 | 1 |

| Discovery | 0.97 | 1 | 0.75 |

| Administrative | 0.84 | 0.58 | 0.38 |

| Investigation | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.68 |

| Legal Research | 0.66 | 1.33 | 0.88 |

| Trial Prep | 1.69 | 1.67 | 1.5 |

| Clerical | 0.62 | 0.83 | 0.69 |

| Court | 1.06 | 1.17 | 0.88 |

| Drafting Documents | 0.66 | 0.83 | 0.75 |