Report Details

Social Determinants of Health in Idaho: Evidence-Based Models for Bridging the Clinical to Community Gap

July 2019

Report Authors

ipi.boisestate.edu

Mcallister Hall, Graduate Research Assistant

Gabe Osterhout, Research Associate

lantz McGinnis-Brown, Research Associate

Vanessa Crossgrove Fry, Research Director

bcidahofoundation.org

Connor Sheldon, Program Officer

Introduction

The focus of modern health care is changing. Today, it is widely recognized that health care doesn’t just happen at the doctor’s office; it happens in our home, work and school environments, and it is impacted by the socioeconomic context, or social determinants of health (SDOH), in those environments.

Recognizing this, the Blue Cross of Idaho Foundation for Health (Foundation) launched the Healthcare Innovation Initiative to bridge the gap between clinical and community services to create business solutions that address this shifting landscape of health care.

SDOH can be addressed through numerous channels in a community, this literature review identifies various programs across the United States (U.S.) that have been implemented and evaluated that can specifically bridge the gap between clinical and community settings and address socio-environmental and socio-economic conditions impacting health outcomes. This report aims to act as a resource and guide in identifying solutions suitable for implementation in Idaho.

Methodology

Four main questions guided this project:

- To date, what has happened to bridge the gap between clinical settings and SDOH to improve health outcomes?

- Where have models been implemented and what stakeholders and resources were involved?

- How have the models created sustainable change?

- What models have potential to scale in Idaho with the support of the Blue Cross of Idaho Foundation?

Answering the first three questions created a foundation for identifying models with potential to scale in Idaho. Research was guided by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of SDOH:

The conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. These forces and systems include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies and political systems.

Innovative models, programs, and policies have been implemented across the U.S. and have proven effective in addressing SDOH and improving health outcomes of entire groups and communities of people rather than directly improving the health of individuals.

Models were identified through a thorough review of associated literature. Literature was accessed through the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute and the School of Medicine and Public Health’s What Works for Health database, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) , as well as directed searches for relevant peer reviewed journal articles. Models were then evaluated on their potential to be implemented in Idaho based on political and legal feasibility and the core competencies of the Foundation including:

technical assistance, capacity building, convening stakeholders, and research. Finally, criteria were identified to aid in future determination of community readiness for each model reported.

Social Determinants of Health in Idaho

The following section, divided into three categories (Health Behaviors, Clinical Care and Social and Environmental Factors), describes certain SDOH impacting Idaho and introduces effective models that could be implemented or scaled up in the state. Suggestions are made regarding the steps necessary for implementation, including resources required and engagement of stakeholders.

Tobacco Use

Tobacco is scientifically proven to cause negative health outcomes among users. Specifically, it is the largest preventable cause of death and chronic disease. Tobacco use reinforces and intensifies existing socioeconomic disparities, in part because secondhand smoke disproportionately affects individuals based on their income, age, sex, and ethnicity. This suggests that tobacco use is an environmental factor that affects people living and working around it, which is based on other social determinants such as socioeconomic standing and physical environment.

Despite ongoing efforts, tobacco-related problems persist in Idaho communities. According to the CDC, in a given year 14.3% of adults in the state smoke cigarettes, leading to 1,800 deaths annually from related illnesses and causing $508 million in direct health care costs. Of Idaho’s 44 counties, 28 have adult smoking rates higher than 15%.

Models

Cessation Therapy Affordability

Tobacco cessation therapy can include individual and group counseling, nicotine products, nasal spray and inhalers, and Bupropion and Varenicline. There is strong evidence that programs making cessation treatment more accessible by lowering out-of-pocket costs are associated with increased quit rates among smokers.

Idaho’s recent passage of Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act has implications for residents’ access to cessation coverage. Since people insured by Medicaid come from a population more likely to smoke cigarettes, expanding eligibility could increase the number of people with access to Medicaid cessation coverage. In 32 other states that expanded Medicaid cessation coverage, 2.3 million total smokers gained eligibility to treatment. Efforts could be made to raise public awareness of these treatment options, as one Medicaid survey previously showed low cessation benefit awareness among tobacco users and health care providers.

Health Care provider reminder systems

CDC research suggests that provider reminder systems “prompt health care providers to screen and intervene with patients around tobacco use and increase provider delivery of cessation advice.” Reminder systems can involve training providers, reimbursement and referral processes, and supplying pamphlets. Tobacco-using patients are 1.6 times more likely to stop smoking after a physician’s recommendation to quit smoking, yet most smokers do not receive such advice.

Among other reasons, physicians cite lack of time, inadequate resources, and lack of cessation clinical skills as barriers to recommending cessation treatment to patients In Idaho, efforts could be made to coordinate with care providers to determine the necessary funding, resources, and technical assistance needed for providers to deliver cessation advice.

Diet and Exercise

Obesity is one of the top factors impacting the nation’s health. Obesity increases the risk of “many of the leading causes of death, including heart disease, stroke, some types of cancer, respiratory diseases, diabetes and kidney disease.” In 2017, 29.3% of adults 18 and older in Idaho were considered obese as were 11% of children aged 2-4 (enrolled in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children or WIC) and 11% of high school students.

Obesity can be influenced by food insecurity and healthy food access. Food insecurity is a measure of the amount of people who at any point in the year have a time when they do not have enough food. In 2017, approximately 16.3% of Idahoans experienced food insecurity, with children experiencing higher levels of food insecurity than adults (22.3%).

Fruit and vegetable prescription program

Fruit and vegetable prescription (FVRx) programs aim to reduce obesity in adults and children by increasing access to healthy foods and providing nutritional education. Prescriptions are written by physicians and are received in the form of vouchers (a set dollar amount per week per family member) for fruits and vegetables at local markets., Approximately 96% of participants are low-income, qualifying for Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), or WIC. The program has proven to decrease Body Mass Index (BMI), increase vegetable consumption, and improve food security.

Wholesome Wave, a non-profit organization that has implemented this program in the U.S., offers support to clinics that wish to incorporate this program into their practice. In addition to clinic participation and support from an organization like Wholesome Wave, this program requires partnerships with local stores and produce providers. This program is commonly funded with grant money. In Idaho, technical support could be given to clinics by facilitating relationships and assisting with grant applications.

Clinic-based food pantries

Food pantries established in clinics or hospitals provide healthy food, nutritional education, and access to a certified dietician for food insecure patients experiencing illnesses related to obesity., Patients must be qualified and then referred by a physician to have access to these pantries., Participating patients can experience weight loss as well as improved blood pressure, blood sugar levels, and relationships with physicians.

Community members occasionally donate food to these clinic pantries, but the majority of the food is provided by local food banks. These programs are most successful when food assistance is combined with personalized nutrition plans created by a certified dietician. For implementation in Idaho, assisting in educating clinics and facilitating relationships with food banks could increase the likelihood of creating clinic-based food pantries.\

Alcohol and Drug Use

Alcohol and drug misuse can lead to a number of health issues including cancer, liver disease and diabetes. It can also impair cognitive abilities and is associated with depression and violent behavior. Although excessive substance misuse is a disease, it is often criminalized.

Idaho is in the top 20 states for opioid prescribing rates with retail opioid prescriptions dispensing rate of 70.3 per 100 people. However, some counties in Idaho have dispensing rates over 100 per 100 people. Counties with higher dispensing rates also tend to have a higher drug overdose mortality rate. In regard to alcohol misuse, certain counties report binge drinking at higher levels than the national average. Certain counties also have higher levels of death due to liver failure, which is often associated with alcohol misuse.

Models

Medication-assisted treatments

Drug and alcohol addiction sometimes requires medication-assisted treatment, often at centers specifically licensed for such treatment. Ensuring individuals with chronic substance misuse issues are connected with appropriate treatments is critical for their long-term health and wellness.

Naloxone, an overdose reversal drug, has been proven successful in reduction of opioid overdose deaths. In 2015, Idaho passed legislation providing civil and criminal immunity to healthcare providers or lay persons providing naloxone administration. Clinics can now legally provide naloxone education and administration to patients, however the prevalence of its use in clinics across the state is unknown at this time. Clinics could proactively work with local law enforcement to distribute information about naloxone efficacy and access. Friends or family members of opioid users would also be key partners in distribution and administration.

Some opioid abusers, and individuals with alcohol addition, may need more intensive, rehabilitative, treatment. Idaho is in the process of opening community crisis centers in all seven of Health and Welfare’s regions of the state that can assist with short-term, medication-assisted treatment. However, patients can only be in a crisis center for less than 24 hours so longer-term treatment needs to take place at another facility. Allumbaugh House in Ada County is the only free of charge location for medication-assisted treatment in the state. Clinics across the state can help direct patients to an appropriate location for treatment and also provide assistance and direction for patients wishing to safely detox outside a medical setting.

Problem-solving courts

Traditional criminal justice approaches have not demonstrated ability to improve recidivism or rehabilitation for individuals with severe substance abuse issues. However, Problem Solving Courts decriminalizing drug and alcohol addiction by diverting nonviolent substance misuse offenders from jail and prison into treatment. This program allows individuals the opportunity to address underlying issues associated with substance misuse They have been proven effective in reducing recidivism and enabling people to more rapidly matriculate back into being a productive member of society.

Idaho’s Problem Solving Courts exist in over 30 counties across the state. Clinics could engage in the Problem Solving Court system by serving as a location for drug testing and monitoring. This may help expand the efficacy of the system in rural areas in the state.

Sexual Activity

Sexual activity can lead to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and unwanted pregnancies. Education on safe sex practices can help decrease the occurrence of these. Compared to the rest of the U.S., Idaho has a relatively low rate of STDs, however, the rate of STD incidences has been steadily increasing over the past decade.

Models

Clinic-based Initiatives

Effective initiatives within clinics to decrease occurrence of STDs and unwanted pregnancies include condom availability programs, comprehensive risk reduction sexual education, HIV/STI partner notification and therapy, and programs for pregnant and parenting teens. The challenge of implementing clinic-based sexual education is removing the stigma around discussing sexual activity so people are comfortable attending clinics to receive care.

These initiatives require participation from local or non-profit clinics as well as other organizations that can help fund the programs. Resources needed include training for those teaching sex education programs and funding to help alleviate costs.

Online Initiatives

There are limited outlets for sex education outside of clinics. In the past decade, the use of social media outlets such as Facebook and YouTube have been used to make sexual education more accessible and comfortable way for people of all ages. These programs have had a small impact so far but have the potential to be more effective as they continue to be evaluated and improved.

These initiatives can be implemented by non-profits or clinics that have the capacity to create web-based education materials and promote those materials. Resources needed include a web-designer, and expert in social media marketing, and funds for advertising to ensure visibility of the web materials.

Access to Care

Access to care means that affordable health care is available when, where, and how it is needed. Lack of adequate access to care can result in unmet health needs, delays in receiving timely care, lack of preventable services, financial burdens, and overutilization of emergency room services. Through improving access to care, the management of chronic conditions and preventative services could be improved.

Health care access differs between rural and urban areas. In Idaho, one in four individuals live in rural areas. A disproportionate amount of the retirement age population, who often require more costly care, live in these rural areas. Implementation of the programs below could be facilitated through educations partnerships with provider-based organization, like the Idaho Medical Association.

Models

Project ECHO

Project ECHO (extension for community healthcare outcomes) provides treatment to patients with chronic or complex diseases who may not have direct access to specialty healthcare providers. Providers participate in Project ECHO via “learning loops” which allows them to learn from peers and comanage patients with other specialists and providers. Participants report increased knowledge, self-efficacy, improved professional opportunity, and enhanced satisfaction.

Project ECHO is currently operating in Idaho with the support of University of Idaho (U of I). Associated learning loops focus on opioid use and behavioral health, this educational resource is empowering primary care providers in rural and remote areas of Idaho to treat complex conditions. Expanding this program could include partnering with U of I, applying for grants and providing technical support for initiating learning loops.

School-based health centers

School-based health centers (SBHCs) provide primary and behavioral health care in a school setting. Some SBHCs have demonstrated Medicaid cost savings and improved health outcomes when targeted to specific populations.

In Idaho, West Ada, Post Falls, and Lakeland School Districts have already collaborated with local non-profit health clinics to create SBHCs., These health centers are sustained by reimbursing services with Medicaid and private payers. A relationship between local physicians, providers and schools is needed to scale these programs. A non-profit organization could assist in facilitating these relationships and providing technical support.

Quality of Care

Improving the connection between community and traditional clinical services could improve the quality of care for Idaho residents. Quality of care includes using evidence-based processes and procedures, delivering care efficiently, providing equal quality of care regardless of personal characteristics, providing patient centered education and support and avoiding harm.

Models

Community health workers

Community health workers (CHWs) are trained in the communities where they serve. The community focus allows the CHW to act as a liaison between the clinic and the community in which they work. There is some evidence that investment in CHWs improves access and coordination of care and social services when focused on specific populations.

Several health providers and health systems in Idaho have invested in CHWs and there is an opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness and value of such services pertaining to specific conditions. Expansion and duplication of these programs could be facilitated through education efforts to such groups as the Idaho Medical Association.

Integrated behavioral health

Integrating behavioral health into primary care settings can improve access and utilization of needed behavioral health services. Integrated behavioral health includes coordination between primary care providers and behavioral health providers, care coordinators, and mental health specialists. Such coordination typically involves additional training and reorganization of staff roles.

Several practices in Idaho are receiving planning and guidance from Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) grant funding to build behavioral health integration into their practices. There is an opportunity to scale this integration and build evaluation strategies to measure value and cost savings/avoidance.

Pathways model of care

The Pathways model improves care coordination for individuals at the highest risk for poor health outcomes through integrating care and providing structured support. One focus on the Pathways model is to invest in and focus on risk factors often associated with poor outcomes and expensive care by better connecting patients to needed social services and supports.

Saint Alphonsus has built several Pathways of care; there is opportunity to expand the model in Idaho. Other providers within the state could be educated on the benefits and workings of the Pathways model and provided with technical support for implementation.

Screen for social determinants of health

Primary care physicians and agencies around the U.S. have started screening for SDOH through various forms of questionnaires (verbal and electronic). Some evidence shows the majority of parents/guardians screened in pediatric clinics have at least one social need and are more likely to report when screened electronically.

Effective screening programs provide patients with referrals for further assistance. For example, a physician may refer a patient suffering with food insecurity to SNAP or a food bank.

There is an opportunity to better educate providers around screening tools and provide technical assistance to develop or provide the necessary infrastructure, especially with continued investment in CHWs and care coordinators.

Education

The Quality Counts Report released by Education Week Research Center ranks Idaho 37th in the nation for student chance-for-success, 49th in per-pupil funding, 46th in adult outcomes, and 42nd in pre-k enrollment through postsecondary education. Improving the quality of education in Idaho will help improve the quality of health.

Models

Early childhood education and Head Start

Early childhood education (ECE) can improve a child’s cognitive and social abilities, their personal health and even the health of their whole family. , Children from low-income families benefit most from ECE programs. Idaho is one of five states that does not offer state-funded preschool. This makes it more difficult for low-income students to attend an ECE program and negatively impacts their health outcomes and academic achievement. , Head Start, a well-known ECE program designed for low-income families, already exists in Idaho. However, the program is limited and it alone is not able to support all the children who need ECE programs. Additional affordable ECE programs are needed, either through duplication of programs like Head Start or through school districts.

Involvement by a number of stakeholders would be required to increase ECE availability. These stakeholders include Head Start, school districts, the Idaho Association for the Education of Young Children (IDAEYC), Idaho Business for Education and legislators. Resources needed to fund ECE programs are extensive. ECE requires facilities, trained teachers, curriculum and school supplies. Working with federally funded Head Start could alleviate the cost burden.

Drop-out prevention and alternative high schools

Helping students complete high school is crucial to improving their future. In seven counties in Idaho, at least 20% of adult residents have not completed high school. In all but five counties in Idaho, at least 70% of the population has only a high school diploma or less. Alternative schools are commonly formed to provide a more accommodating learning environment for at-risk students. Many of these schools exist in Idaho, but there are many areas that might need an alternative school but do not have the technical support for creation. Dropout prevention programs are also effective in student retention and are much lower-cost than alternative schools. Dropout prevention programs can include: work-study programs, community service programs, counseling, vocational training, college preparation mentoring and schedule restructuring.

Stakeholders involved include school districts and potentially local professionals, if vocational training and work-study programs are involved. Resources needed for dropout prevention programs include training and pay for staff. Resources needed for creating an alternative school includes providing technical assistance in identifying a need and communicating that need to the state.

Employment

Employment serves as a driver of an individual’s economic standing. For instance, work can “provide financial security, social status, personal development, social relations, and self-esteem and protection from physical and psychological hazards.” Models addressing employment issues are especially useful for young adults with high school diplomas or GEDs. The state’s high school graduation rate is 80% but a much smaller rate of students successfully pursue higher education. 27 of the state’s 44 counties have populations with fewer than 60% partial college completion rates.

Models

Sector-based workforce initiatives and career pathways programs

Sector-based workforce initiatives “prepare unemployed and underskilled workers for skilled positions and connect them with employers seeking to fill such vacancies”, which has been proven to increase employment more than other worker development programs. Seeking a similar goal, career pathway programs help students pursue industry-specific careers through targeted training opportunities. Each model benefits similar populations: low-income and skilled adults, disadvantaged workers, the long-term unemployed and out-of-school youth. Idaho does have state-level targeted sector activities.

In Idaho the expansion of sector-based initiatives and career pathways can involve collaboration of a number of sectors including formal education and job training providers, like apprenticeship programs. Community organizations, such as economic development entities, and state agencies, such as Idaho Department of Labor are also key stakeholders for program expansion.

Adult vocational training and bridge programs

Vocational training and bridge programs specifically target and benefit young adults, unemployed individuals, and low-education populations by providing job-specific education and training. There are opportunities to expand vocational training opportunities in Idaho. Job Corps, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Labor, offers vocational training at a Nampa center capable of serving 260 students. The program offers training in welding, carpentry, electrical work, and other trades.

In another example, stakeholders could push to have Idaho join 21 other states in receiving grants administered by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services to train low-income individuals for high-demand opportunities in the health sector. Stakeholders from various sectors have secured these grants for their home states, such as education, private investment, state agency, nonprofit, and health care organizations, yet no stakeholders in Idaho have successfully secured grant money for the state.

Income

The relationship between income and health is a positive feedback loop: the improvement or deterioration of income can impact one’s health in a similar direction. Low-income individuals often experience a range of negative clinical, behavioral and environmental factors. In Idaho, income-related issues are seen in the numbers of residents without savings and children living in poverty. For instance, a substantial number of residents lack adequate savings. The state has a high rate of liquid asset poverty, or the “share of households with insufficient liquid assets. . . to subsist at the poverty level for three months.” Two in five Idahoans are estimated to be liquid asset poor. Moreover, many communities in the state are in need of an intervention to reduce the number of families with children living below the poverty line: 15% of Idaho children are experiencing poverty, including 17 counties where one in five children live in poverty, and all 44 counties’ rates in recent years have either stayed the same or gotten worse. Similarly, 46% of Idaho children are eligible for free or reduced price lunch at school, and at least half of all children in 21 counties are qualified.

Models

Child development accounts

The goal of child development accounts (CDAs) is to help families save money for their children from an early age, usually to increase their confidence that college is an achievable opportunity. CDAs have been proven to “positively affect ownership of college savings accounts and assets, educational expectations, and other indicators of well-being.” These models can be made available to all school-age children but are especially effective in helping low-income children save for higher education. In Idaho, the City of Caldwell partners with banking and investment organizations to offer CDAs to students in Kindergarten through 5th grade. Its model aims to offer monetary assistance while also teaching students how to create and expand their savings, with a larger goal of demonstrating the importance of financial literacy.

Caldwell’s piloted model represents an opportunity for replication to other communities in the state. Implementing new CDAs, either through education-specific programs or by targeting broader income-based goals, would require technical assistance, evaluation and monitoring, and possibly funding to assist relevant stakeholders such as cities, state agencies, or school districts.

Family and Social Support

Family and social support includes the interactions and relationships that meet a person’s basic needs for social integration, including needs for approval, mentorship and affection.

Recent research suggests that a lack of family and social support (information sharing, resource sharing, and emotional/psychological support) can negatively affect stress levels and associated physiological responses,, including mental health, and overall wellness., Idaho consistently ranks among the top ten states with the highest suicide rate per capita.

Models

Intergenerational mentoring

Intergenerational mentoring (including the Big Brothers Big Sisters (BBBS) program model) connects older volunteer mentors with at-risk youth mentees to encourage academic and social development and to discourage criminal behavior. This approach also addresses the Community Safety and Drug and Alcohol Use determinants of health through its attempted reduction of youth crime and substance use.

Results include mentees being 46% less likely to start taking illegal drugs and 27% less likely to start using alcohol. In Idaho, 27% of high school students report regularly drinking alcohol while 9% report regular tobacco use. A BBBS program is operating in southwest Idaho, but similar programming does not seem to be present in other regions of the state.

This program requires a network of volunteer mentors, as well as a coordinator or facilitator to provide oversight. Clinics can become involved by referring parents and guardians to programs like Big Brothers Big Sisters. Resources would likely need to be provided to establish this program initially, and potentially to maintain a coordinator oversight position.

Parental involvement programs

Parental involvement programs seek to increase the role that parents, particularly fathers, play in their children’s lives through training, education, support, and facilitation of father-child interactions. One such program is the Nurturing Fathers program, which involves a 13-week training course designed to teach parenting skills. Parental involvement programs typically employ a group setting, which can help to facilitate ongoing peer support among program participants.

Idaho’s Third Judicial District has a family court services department that offers parent education classes, including at-home training. It remains unclear whether similar services are offered elsewhere in Idaho on a consistent basis. In order to support programs like this, resources would need to be provided for initial “train the trainer” sessions, and potentially to maintain the trainer positions. A training location is also necessary.

Social service integration

Social service integration seeks to coordinate a wide variety of programs and services through increased collaboration and communication. This can be done in a variety of ways. One popular approach is to create a “one-stop office model”, in which clients only need to go to one office to access multiple services and coordinated, need-based case management support.

The Interfaith Sanctuary emergency homelessness shelter has attempted to facilitate this type of service integration through their “Monday Meet-Ups”, which bring together multiple agencies that serve people experiencing homelessness to increase access and coordination of services.

Social service integration requires buy-in from the agencies and actors that are sought for collaboration. This approach can be supported by third-party mediators and coordinators that are able to bring together interested agencies and to manage the strengths and weaknesses of different agencies as part of the entire system.

Youth leadership programs

Youth leadership programs seek to teach youth how to better interact with people and solve problems, leading in turn to empowerment and improved self-esteem. These programs can take a wide variety of forms, with a wide variety of expected outcomes, but the general focus is on socialization, relationship-building, and problem solving.

The Treasure Valley Family YMCA offers youth leadership training courses for teenagers and the Boise School District offers an after-school program called “Everyday Leadership” for low-income students. The University of Idaho also manages a statewide 4H program that focuses on personal development for kids aged 5 to 18. Finally, Boise State University offers a Youth Leadership Forum for high school juniors and seniors.

Because they can take diverse forms, youth leadership programs can be implemented in different ways through different organizations, including schools, nonprofit organizations and local governments. At least one trainer/leader is generally required to guide the program, and space for the program is required. These programs could be supported through funding to pay for transportation, training, staff positions, space, or activities.

Early childhood home visiting programs

Early childhood home visiting programs (including the Nurse-Family Partnership (NPF) program model and the Healthy Families America (HFA) program model connect childcare professionals to at-risk families with young children (under two, generally), or families expecting children. These professionals teach parenting skills and provide childcare support with the goal of preventing child injury, abuse, and/or neglect. These programs can help to bridge the gap between clinic and community by extending pre and post-natal care to the home. This approach addresses the community safety determinant of health by preventing harm to children and saves money from the government and societal perspectives.

Idaho’s Department of Health and Welfare offers a Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting program, which connects parents of children under three with nurses, social workers, or other early childhood professionals that can provide training, support, and service coordination. Idaho also has NFP programs operating in Bonner, Canyon, Kootenai and Shoshone counties. These programs require nurses or other trained professionals to visit families, which in turn requires training and transportation. These programs could be supported through funding to pay for transportation, training, or staff positions.

Community Safety

Community safety refers to the risk of death or injury caused by crime, negligence, or accident. Perceptions about these risks also affect individual health outcomes related to community safety.

Violent crime, including domestic crime, is a clear threat to public health and safety, but trauma and stress related to violent crime and feelings of danger also have negative impacts on individual health outcomes, including stress levels, mental health and physiological health. Other crimes and negligent behaviors, such as driving irresponsibly or biking without a helmet, can also lead to death, injury and trauma. This array of factors points to a need for comprehensive, “wraparound” programs that address not only criminal/negligent behavior, but the many environmental conditions that lead to it, and the conditions that it may cause.

Models

Summer youth employment programs

Summer youth employment programs are intended to provide jobs over the summer to at-risk youth, with the goal of occupying their time, providing financial opportunities, and combating boredom and other factors that can lead youth to commit crimes. By providing job experience, these programs are also thought to improve future opportunities for participating youth.

Through a Federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) program, the Idaho Department of Labor provides education, training, and employment opportunities to low income youth aged from 16 to 24. The Idaho Youth Ranch also offers a YOUTHWORKS! summer job training program for those aged 16-24 years old.

Youth employment programs have been developed by both governments and nonprofit organizations. The success of these programs requires a source of jobs, which can either come from government, nonprofit organizations, or private businesses. Support can be provided to these programs through coordination and training to connect youth with available jobs and to prepare them for those jobs.

Child safety equipment distribution and education programs

These programs seek to raise awareness about the importance of equipment, such as bike helmets and child car seats, in preventing injuries to children. Some programs will also provide free or discounted equipment to families that need them.

These programs are targeted toward families with children, particularly low-income families with children that may not have equipment. Educational materials and classes may also be provided.

In the Treasure Valley, the Canyon County Paramedics, Middleton Fire Department, and St. Luke’s Children’s Car Seat program all offer car seats to Idaho families with small children for free with a suggested donation up to 30 dollars, while also providing training and safety checks for seat installations. The Idaho Transportation Department offers educational materials on child bicycle helmet usage and benefits, as well as free child car seat safety checks. The Boise Bicycle Project organization also offers a Bicycle Skills and Safety Hour (BASH) in the summer for kids aged 4 to 11, after which kids receive free bikes and helmets.

These programs can be supported by providing funding for educational materials and educators and helmets. Coordination between equipment distributors, donors and recipients can also be an important factor in the success of these programs.

Housing and Transportation

Accessible housing and transportation are intertwined determinants impacting one’s ability to lead a healthy, productive life. An affordable home near accessible multimodal transportation options can connect people to opportunities necessary for a healthy life including education, employment, health care and social and cultural activities. Population growth in Idaho will continue to put pressure on the current urban and rural housing stock and transportation systems. Helping all Idahoans connect to safe, affordable housing and access multimodal transportation will reduce health disparities and support a healthy population and strong economy.

Housing Models

Shelter itself is a basic human need. Housing instability has been linked to a number of health issues including mental health and substance misuse problems. Youth and seniors are particularly vulnerable. Housing stability, however, has been linked to better health and improved quality of life. In addition, housing cost burden on individuals and families can compete with spending on food and health care which can lead to negative health outcomes.

Idaho is considered to be one of the fastest growing states in the U.S. with the Treasure Valley being the fastest growing metropolitan area in the state. The growth in housing stock has not kept pace with population growth. This has led to lower vacancy rates (both rental and ownership) which has resulted in increased housing costs. The cascading effect disproportionately impacts lower income individuals and families.

Health impact assessments and healthy home programs

Aging housing stock is often the housing that is affordable for low income members of a community, however may be unsafe to live in. This includes housing with allergens, pests, and insufficient insulation. Health impact assessments (also known as healthy home environmental assessments) can identify risks and appropriate remediation measures. Healthy home programs, like the Green and Healthy Homes Initiative (GHHI), can provide funding to modernize housing units for low income tenants. Such programs lead to lower utility costs and a reduction in health care spending, particularly on emergency room visits.

The state of health of Idaho’s housing stock is unknown, but clinics can help identify where housing may be an issue impacting a patient’s health and facilitate healthy home environmental assessments with the partnerships of nonprofits, like GHHI.

Health action plans

Community-based health action plans have been utilized to address housing issues in a number of communities. Creating a community health action plan involves evaluating the health attitudes and conditions of a community and forming a plan of action to improve health education and outcomes. Such a process could also be utilized for other SDOH outside of housing.

Communities may require technical assistance for evaluating community needs, as well as assistance in creating relationships between government officials and health experts. Implementation of plans requires community buy in and often financial support.

Housing navigators

A challenge associated with accessing affordable housing is being able to navigate the assistance programs available in a community. Housing navigators help people access the resources they need to find and move in to a safe, stable, affordable home. Such services include the local coordinated entry system, eviction prevention services, and other wrap around supportive services which enable tenants to remain housed.

By partnering with the state’s coordinated entry systems, health clinics across the state can direct people to resources necessary to address their housing crises. There is also an opportunity to provide a more comprehensive approach to housing crises by supporting efforts to coordinate prevention services with housing services as they are currently segregated in most parts of the state.

Transportation Models

Well planned, multimodal transportation systems can enable access to social and economic resources necessary for a healthy lifestyle. Both urban and rural public transportation options allow people to access health care, healthy food options, and social activities. However, public transportation in Idaho is limited. Although urbanized areas have some transit options, more often it is not accessible to many affordable housing options.

Transportation voucher programs

Accessing healthy food and health care can be nearly impossible for someone unable to access safe, affordable transportation. Clinics can partner with local transit agencies or demand response services, like Uber and Lift, to distribute vouchers to patients in need of transportation.

Demand response

Public transportation systems across the state are required to provide a demand response service to individuals unable to access a traditional transit stop. Clinics can partner with local transit agencies to inform patients in need of transportation of the demand response option.

This literature review is meant to serve as a resource and guide in identifying solutions that bridge the gap between clinical and community settings. The success of the models presented depends on community readiness. The following criteria have been created to assist in identifying community readiness. These criteria include impact, innovation, community champion presence and political, technical, and legal feasibility (see Appendix for definitions).

Each of these criteria are important to consider when conducting a cost-benefit analysis. A community with higher impact capacity can reach more people using similar funds as a community with low capacity for impact. If a community is not prepared for the innovative intervention, more time and money would need to be spent to prepare the community before the program can be established. If a model is not politically feasible, money could be spent on a program that no one uses. Implementation would also become more costly in a community without the technical feasibility for a program.

The goal of this review was to provide a list of evidence based (and innovative) models, programs, and policies that have been implemented across the U.S. and have proven effective in addressing SDOH and improving health outcomes. However, the state of Idaho and various agencies lack the political or economic capacity for many effective programs. The programs included in the review were also limited to the capabilities of the Blue Cross of Idaho Foundation. The Foundation is able to provide technical support in establishing programs; however, it is limited by funding, political and institutional relationships that prevent its ability to facilitate the implementation of large-scale programs. For example, interventions improving air and water quality, common SDOH, are not discussed in this review because of limited capacity.

Addressing SDOH in general comes with limitations, especially when initiatives are clinic-based. The populations that often need the most assistance are least likely to seek help in a clinic, especially for preventative care. Furthermore, the social nature of SDOH suggests that once an issue becomes an individual crisis, the opportunity for preventative intervention diminishes (Marmot, Allen, Bell, Bloomer, & Goldblatt, 2012; Marmot et al., 2008; Marmot & Wilkinson, 2005). Reaching the target population can be difficult and involves building strong relationships in the community. If the target population is not considered, the program risks impacting a small population with less need., This can lead to skewed evaluation results, giving the illusion of improvement without impacting the population with the most need.

The following steps can assist the Foundation in bridging the gap between clinical and community services to address SDOH in Idaho. An important part of implementing programs or policies will be engaging local clinics and ensuring they have the most up to date information and understanding regarding SDOH. The more that clinics know about and understand SDOH, the more likely they are to assist in implementing interventions.

Successful implementation of models and programs is also dependent on community readiness. The criteria listed above can help determine which communities will be most receptive to programs addressing SDOH. Engaging with the right communities will influence the outcome of implementation.

After initial selection of a community for implementation, the Foundation can facilitate a heath impact assessment within the community. The assessment process can help further engage community stakeholders and refine the focus of the intervention. Following the assessment process, the Foundation can work with stakeholders to design of a community-based health action plan to address the environmental and socio-economic issue(s) identified to be most impacting the community.

Ongoing evaluation is an essential step to understanding successful implementation as well as the impact of the Foundation. Evaluation design should occur after a community and program have been selected but before the actual implementation. A community health assessment could serve as a baseline evaluation for the community to use to measure progress in addressing identified issues. Evaluation will ultimately enable the Foundation and communities the opportunity to refine application of the models, programs, and policies that have been implemented and allow for an impactful improvement in the SDOH impacting Idaho.

Definitions

Health care (noun): the act of preventing, treating, or sustaining health.

Healthcare (adjective): describes the system or industry of providing care.

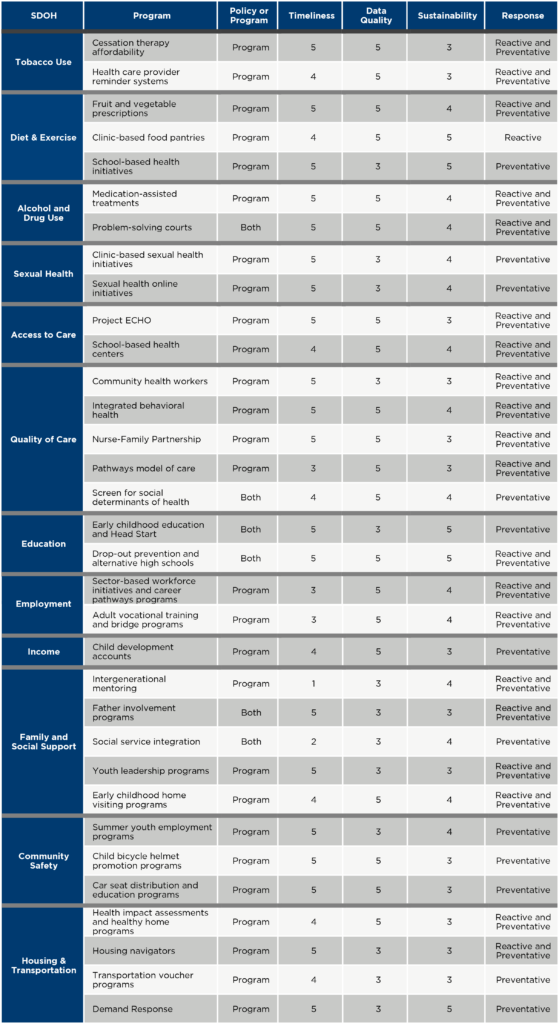

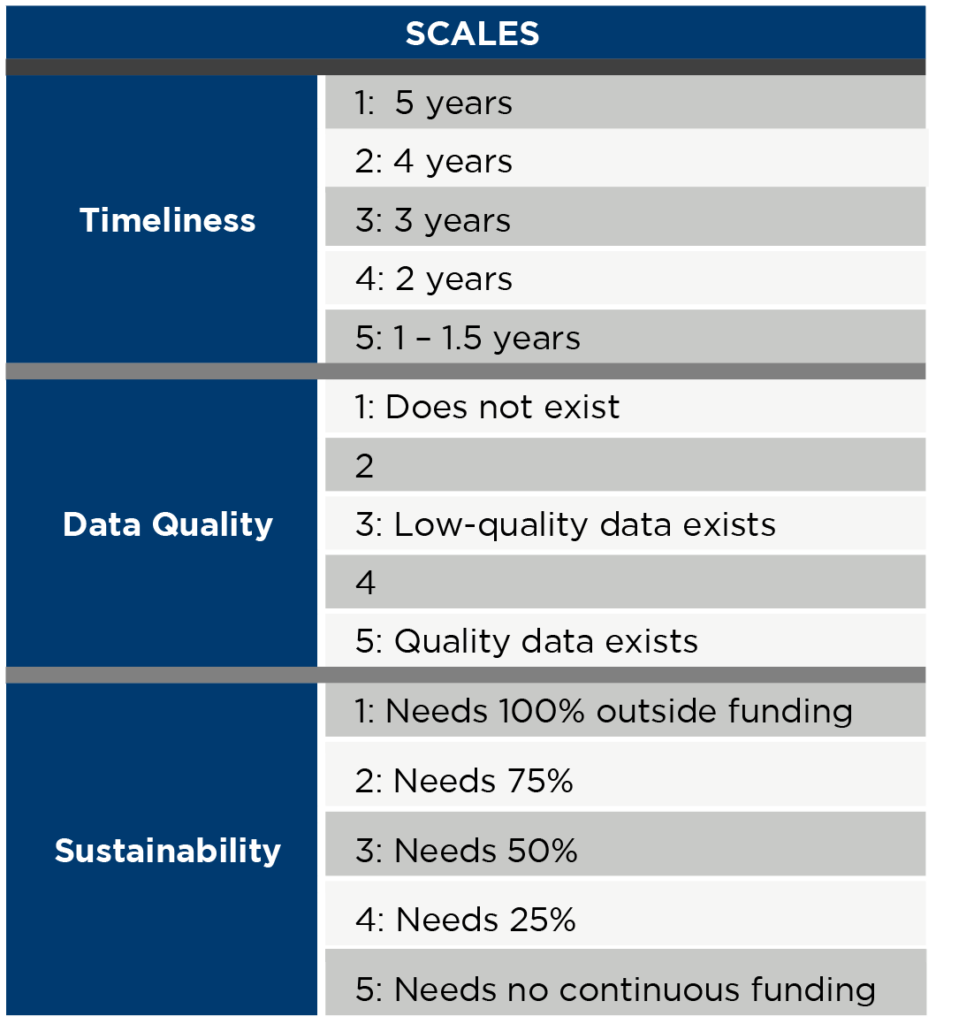

Model Ratings

The following table includes each model discussed in the paper and evaluates the timeliness, sustainability, and data quality of each on scales of one to five – one being least preferable for investment, five being most preferable. The table also describes each initiative as a program or a policy and as preventative or reactive. The table provides five criteria to evaluate the models: whether it is a policy or program, timeliness, data quality, sustainability and response.

Model Type indicates whether the model discussed is a policy or programmatic in nature.

Timeliness refers to the timeliness of implementation. On a scale of one to five, a ‘five’ signifies a program that can be fully established in 18 months or less, a ‘four’ signifies two years, ‘three’ is three years, ‘two’ is four years, and a ‘one’ is a program that would take five or more years to implement.

Data Quality refers to the quality of the data available to measure the impact of a program. A ‘five’ signifies that quality data current exists for evaluation, a ‘three’ signifies that poorly collected or possibly biased data exists for evaluation and programs receiving a ‘one’ lack prior data to measure impact.

Sustainability refers to the financial capacity of a program to be sustained after receiving initial funding assistance. A ‘five’ in this category is a program that can be sustained with no additional funding after implementation. A ‘four’ is a program that would need between 25% funding, a ‘three’ is 50%, ‘two’ is 75%, and a ‘one’ is a program that would need full funding to continue function after implementation.

Response indicates whether the model is reactive to an issue associated with SDOH or it is a preventative measure.

This report was prepared by Idaho Policy Institute at Boise State University and Blue Cross of Idaho Foundation for Health, Inc. and commissioned by Blue Cross of Idaho Foundation for Health, Inc.

World Health Organization. (2019). Social determinants of health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/.

Adler, N. E., & Newman, K. (2002). Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Affairs, 21(2), 60–76.

Hardy, L. J., Bohan, K. D., & Trotter, R. T. (2013). Synthesizing Evidence-Based Strategies and Community-Engaged Research: A Model to Address Social Determinants of Health. Public Health Reports, 128(6_suppl3), 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549131286S311

Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., Houweling, T. A., Taylor, S., & Health, C. on S. D. of. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 372(9650), 1661–1669.

University of California, San Francisco, Adler, N. E., Cutler, D. M., Harvard University, Fielding, J. E., University of California, Los Angeles, … Morehouse School of Medicine. (2016). Addressing Social Determinants of Health and Health Disparities: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care. NAM Perspectives, 6(9). https://doi.org/10.31478/201609t

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2014). The Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/tobacco/index.html.

David, A., Esson, K., Perucic, A., & Fitzpatrick, C. (2010). Tobacco use: equity and social determinants. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/social_determinants/tools/EquitySDandPH_eng.pdf#page=209.

University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. (2010). What Works for Health: Tobacco Use. Retrieved from http://whatworksforhealth.wisc.edu/factor.php?id=15.

CDC. (2019). Extinguishing the Tobacco Epidemic in Idaho. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/about/osh/state-fact-sheets/pdfs/idaho-2019-h.pdf.

University of Wisconsin Health Population Institute. (2019). County Health Rankings & Roadmaps: Idaho. Retrieved from http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/idaho/2019/overview.

DiGiulio, A., Haddiz, M., Jump, Z., Babb, S., Schecter, A., Williams, K.S., Asman, K., & Armour, B.S. (2016). State Medicaid Expansion Tobacco Cessation Coverage and Number of Adult Smokers Enrolled in Expansion Coverage. Weekly, 65(48), 1364-1369.

Community Guide. (2012). Tobacco Use and Secondhand Smoke Exposure: Reducing Out-of-Pocket Costs for Evidence-Based Cessation Treatments. Retrieved from https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/tobacco-use-and-secondhand-smoke-exposure-reducing-out-pocket-costs-evidence-based-cessation.

DiGiulio, A., Haddiz, M., Jump, Z., Babb, S., Schecter, A., Williams, K.S., Asman, K., & Armour, B.S. (2016). State Medicaid Expansion Tobacco Cessation Coverage and Number of Adult Smokers Enrolled in Expansion Coverage. Weekly, 65(48), 1364-1369.

Ibid.

Community Guide. (2012). Tobacco Use and Secondhand Smoke Exposure: Reducing Out-of-Pocket Costs for Evidence-Based Cessation Treatments. Retrieved from https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/tobacco-use-and-secondhand-smoke-exposure-reducing-out-pocket-costs-evidence-based-cessation.

CDC. (2014). Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs. p. 42. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/pdfs/2014/comprehensive.pdf.

University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. (2010). What Works for Health: Tobacco Use. Retrieved from http://whatworksforhealth.wisc.edu/factor.php?id=15.

Caplan, L., Stout, C., & Blumenthal, D.S. (2011). Training Physicians to Do Office-based Smoking Cessation Increases Adherence to PHS Guidelines. Journal of Community Health, 36(2), 238-243.

Ibid.

Hales, C., Carroll, D., Fryar, C., & Ogden, C. (2017). Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth, United States, 2015-2016. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

CDC. (2013). CDC national health report highlights. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

United Way of Treasure Valley. (2017). United Way of Treasure Valley 2017 community assessment. United Way.

Rose, D. (1999). Economic determinants and dietary consequences of food insecurity in the United States. The Journal of Nutrition, 129(2), 517S-520S.

Gundersen, C., A. Dewey, A. Crumbaugh, M. Kato & E. Engelhard. Map the Meal Gap 2018: A Report on County and Congressional District Food Insecurity and County Food Cost in the United States in 2016. Feeding America, 2018.

Ibid.

Aubrey, A. (2013). No bitter pill: doctors prescribe fruits and veggies. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2013/09/12/221757539/no-bitter-pill-doctors-prescribe-fruits-and-veggies.

Wholesome Wave. (2018). Fruit and vegetable prescription program. Wholesome Wave.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Hess, A., Passaretti, M., Coolbaugh, S. (2019). Fresh food farmacy. American Journal of Health Promotion, 33(5), 830-832.

Wetherill, M. S., McIntosh, H. C., Beachy, C., & Shadid, O. (2018). Design and Implementation of a Clinic-Based Food Pharmacy for Food Insecure, Uninsured Patients to Support Chronic Disease Self-Management. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 50(9), 947-949.

Boston Medical Center. (2019). Preventative food pantry. Retrieved from https://www.bmc.org/nourishing-our-community/preventive-food-pantry.

Hess, A., Passaretti, M., Coolbaugh, S. (2019). Fresh food farmacy. American Journal of Health Promotion, 33(5), 830-832.

Ibid.

Wetherill, M. S., McIntosh, H. C., Beachy, C., & Shadid, O. (2018). Design and Implementation of a Clinic-Based Food Pharmacy for Food Insecure, Uninsured Patients to Support Chronic Disease Self-Management. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 50(9), 947-949.

Ibid.

McGinnis, A. (2019). Clinic-based food bank supports vulnerable patients. Retrieved from

https://www.midwestmedicaledition.com/2019/03/27/191639/clinic-based-food-bank-supports-vulnerable-patients.

Hess, A., Passaretti, M., Coolbaugh, S. (2019). Fresh food farmacy. American Journal of Health Promotion, 33(5), 830-832.

Ibid.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). U.S. opioid prescribing rate maps. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxrate-maps.html

Ibid.

Idaho Health and Welfare. (2018). 2017 Mortality: Idaho vital statistics. Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, Division of Public Health, Bureau of Vital Records and Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://healthandwelfare.idaho.gov/Portals/0/Health/Statistics/2017-Reports/2017_Mortality.pdf

Ibid.

Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System. (2017). Naloxone overdose prevention laws. Retrieved from http://www.pdaps.org/datasets/laws-regulating-administration-of-naloxone-1501695139

Heilbrun et al. (2012). Community-based alternatives for justice-involved individuals with severe mental illness: Review of the relevant research. Criminal Justice and Behavior 39, 351-419.

Berman, G. & Feinblatt, J. (2015). Good courts: The case for problem-solving justice. New Orleans: Quid Pro Books.

The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. (2010). Behind bars II: Substance abuse and American’s prison population. New York: Columbia University.

Guse, K., Levine, D., Martins, S., Lira, A., Gaarde, J., Westmorland, W., & Gilliam, M. (2012). Interventions using new digital media to improve adolescent sexual health: a systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(6), 535-543.

Idaho Department of Health & Welfare, Division of Public Health. (2017). Idaho reported sexually transmitted disease 2017. Idaho Department of Health & Welfare.

University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. (n.d.). What Works for Health: Intergenerational mentoring. Retrieved from http://whatworksforhealth.wisc.edu/factor.php?id=14.

Guse, K., Levine, D., Martins, S., Lira, A., Gaarde, J., Westmorland, W., & Gilliam, M. (2012). Interventions using new digital media to improve adolescent sexual health: a systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(6), 535-543.

Ibid.

Nguyen, P., Gold, J., Pedrana, A., Chang, S., Howard, S., Ilic, O., … & Stoove, M. (2013). Sexual health promotion on social networking sites: a process evaluation of The FaceSpace Project. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1), 98-104.

Pedrana, A., Hellard, M., Gold, J., Ata, N., Chang, S., Howard, S., … & Stoove, M. (2013). Queer as F** k: reaching and engaging gay men in sexual health promotion through social networking sites. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(2), e25.

Ibid.

Ibid.

University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. (n.d.). What Works for Health: Intergenerational mentoring. Retrieved from http://whatworksforhealth.wisc.edu/factor.php?id=16

Douthit, N., Kiv, S., Dwolatzky, T., & Biswas, S. (2015). Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health, 129(6), 611-620.

Wolkenhauer, S. (2018). The future of rural Idaho. Idaho Department of Labor.

Arora, S. (2008). Project ECHO: Extension for community healthcare outcomes.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Koenig, K. T., Ramos, M. M., Fowler, T. T., Oreskovich, K., McGrath, J., & Fairbrother, G. (2016). A statewide profile of frequent users of school‐based health centers: implications for adolescent health care. Journal of School Health, 86(4), 250-257.

School-Based Health Alliance (2012). 2010-2011 Census report of school-based health centers. School-Based Health Alliance.

Family Medicine Health Center (2019). Meridian schools clinic. Retrieved from https://www.fmridaho.org/patients/locations/meridian-schools-clinic/.

Heritage Health (2019). School-based health center. Retrieved from https://myheritagehealth.org/programs/school/.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2018). Understanding quality measurement. Retrieved from https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html.

Lehmann, U. & Sanders, D. (2007). Community health workers: what do we know about them. World Health Organization.

Ibid.

Viswanathan, M., Jennifer, K., Nishikawa, B., Morgan, L., Thieda, P., Honeycutt, A., Lohr, K., Jonas, D. (2009). Outcomes of community health worker interventions. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions (n.d.) Integrating behavioral health in primary care. Retrieved from https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/behavioral-health-in-primary-care.

PCHCP. (2016). Pathways community HUB manual: a guide to identify and address risk factors, reduce costs, and improve outcomes. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Ibid.

Gottlieb, L., Hessler, D., Long, D., Amaya, A., & Adler, N. (2014). A randomized trial on screening for social determinants of health: the iScreen study. Pediatrics, 134(6), e1611-8.

Garg, A., Toy, S., Tripodis, Y., Silverstein, M., & Freeman, E. (2015). Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics, 135(2), e296.

Education Week. (2019). Educational opportunities and performance in Idaho. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2019/01/16/highlights-report-idaho.html.

Hahn, R. A., & Truman, B. I. (2015). Education improves public health and promotes health equity. International Journal of Health Services, 45(4), 657-678.

Anderson, L. M., Shinn, C., Fullilove, M. T., Scrimshaw, S. C., Fielding, J. E., Normand, J., … & Task Force on Community Preventive Services. (2003). The effectiveness of early childhood development programs: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 24(3), 32-46.

Thornton, R. L., Glover, C. M., Cené, C. W., Glik, D. C., Henderson, J. A., & Williams, D. R. (2016). Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health Affairs, 35(8), 1416-1423.

Hahn, R. A., & Truman, B. I. (2015). Education improves public health and promotes health equity. International Journal of Health Services, 45(4), 657-678.

United Way of Treasure Valley. (2017). United Way of Treasure Valley 2017 community assessment. United Way.

Hahn, R. A., & Truman, B. I. (2015). Education improves public health and promotes health equity. International Journal of Health Services, 45(4), 657-678.

Thornton, R. L., Glover, C. M., Cené, C. W., Glik, D. C., Henderson, J. A., & Williams, D. R. (2016). Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health Affairs, 35(8), 1416-1423.

O’Gorman, E., Salmon, N., & Murphy, C. A. (2016). Schools as sanctuaries: A systematic review of contextual factors which contribute to student retention in alternative education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(5), 536-551.

Steinka-Fry, K. T., Wilson, S. J., & Tanner-Smith, E. E. (2013). Effects of school dropout prevention programs for pregnant and parenting adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 4(4), 373-389.

Ibid.

Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., Houweling, T., & Taylor, S. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 372, 1663.

Roder, A., & Elliott, M. (2014). Sustained Gains: Year Up’s Continued Impact on Young Adults’ Earnings. Retrieved from https://economicmobilitycorp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Sustained-Gains-Summary.pdf.

University of Wisconsin Health Population Institute. (2019). County Health Rankings & Roadmaps: Idaho. Retrieved from http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/idaho/2019/overview.

Maguire, S., Freely, J., Clymer, C., Conway, M., & Schwartz, D. (2010). Tuning In to Local Labor Markets: Findings From the Sectoral Employment Impact Study. p. 2. Retrieved from https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/2017/05/TuningIntoLocalLaborMarkets-ExecSum.pdf.

Ibid.

Hossain, F. (2014). Serving Out-of-School Youth Under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. Retrieved from https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/Serving_Out-of-School_Youth_2015%20NEW.pdf.

Gasper, J.M., Henderson, K.A., & Berman, D.S. (2017). Do Sectoral Employment Programs Work? New Evidence from New York City’s Sector-Focused Career Centers. Industrial Relations, 56(1), 40-72.

King, C.T., Juniper, C.J., Coffey, R., & Smith, T.C. (2016). Promoting Two-Generation Strategies: A Getting-Started Guide for State and Local Policymakers. Retrieved from https://www.fcd-us.org/assets/2016/10/TwoGenGuideRevised2016.pdf.

Couch, K.A., Ross, M.B., & Vavrek, J. (2017). Career Pathways and Integrated Instruction: A National Program Review of I-BEST Implementations. Journal of Labor Research, 39(1), 99-125.

Job Corps. (n.d.). Centennial Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center. Retrieved from https://centennial.jobcorps.gov/.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2019). What is HPOG? Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/hpog/what-is-hpog.

Ibid.

Health Affairs. (2018). Health, Income, & Poverty: Where We Are & What Could Help. Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180817.901935/full/.

Mills, G.B. (2012). Liquid asset poverty and prolonged joblessness: The recession ripples on. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/liquid-asset-poverty-and-prolonged-joblessness-recession-ripples.

Saunders, E.R. (2013). New Report Shows Many Idahoans Don’t Have Adequate Savings. Retrieved from https://stateimpact.npr.org/idaho/2013/01/30/new-report-shows-many-idahoans-dont-have-adequate-savings/.

University of Wisconsin Health Population Institute. (2019). County Health Rankings & Roadmaps: Idaho. Retrieved from http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/idaho/2019/overview.

Ibid.

Sherraden, M., Clancy, M., Nam, Y., Huang, J., Kim, Y., Beverly, S., Mason, L.R., Williams Shanks, T.R., Wikoff, N.E., Schreiner, M., & Purnell, J.Q. (2018). Universal and Progressive Child Development Accounts: A Policy Innovation to Reduce Education Disparity. Urban Education, 53(6), 806.

Prosperity Now. (n.d.). Find a Children’s Savings Program. Retrieved from https://prosperitynow.org/map/childrens-savings.

Ibid.

City of Caldwell. (2018). Caldwell Saves First. Retrieved from https://www.cityofcaldwell.org/live/youth-master-plan/caldwell-saves-first.

Kaplan, B. H., Cassel, J. C., & Gore, S. (1977). Social support and health. Medical care, 15(5), 47-58.

LaRocco, J. M., House, J. S., & French Jr, J. R. (1980). Social support, occupational stress, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 202-218.

Gore, S. (1978). The effect of social support in moderating the health consequences of unemployment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 157-165.

Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health, 78(3), 458-467.

House, J. S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865), 540-545.

Uchino, B. N., Cacioppo, J. T., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (1996). The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin, 119(3), 488.

Idaho Department of Health and Welfare (2018). Suicide in Idaho [Fact Sheet]. Retrieved from https://healthandwelfare.idaho.gov/Portals/0/Users/145/93/2193/Fact%20Sheet_September%202018.pdf

Tierney, J. P. (1995). Making a Difference. An Impact Study of Big Brothers/Big Sisters.

U.S. Health and Human Services. (2017), Idaho Adolescent Substance Abuse Facts. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/facts-and-stats/national-and-state-data-sheets/adolescents-and-substance-abuse/idaho/index.html

University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. (2016). What Works for Health: Intergenerational mentoring. Retrieved from http://whatworksforhealth.wisc.edu/program.php?t1=20&t2=6&t3=84&id=326.

University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. (2016). What Works for Health: Father involvement programs. Retrieved from http://whatworksforhealth.wisc.edu/program.php?t1=20&t2=6&t3=121&id=438.

Waldfogel, J. (1997). The new wave of service integration. Social Service Review, 71(3), 463-484.

Ricketts, J. C., & Rudd, R. D. (2002). A comprehensive leadership education model to train, teach, and develop leadership in youth. Journal of Career and Technical Education, 19(1), 7-17.

Olds, D. L. (2006). The nurse–family partnership: An evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27(1), 5-25.

Miller, T. R. (2015). Projected outcomes of nurse-family partnership home visitation during 1996–2013, USA. Prevention Science, 16(6), 765-777.

Whitley, R., & Prince, M. (2005). Fear of crime, mobility and mental health in inner-city London, UK. Social Science & Medicine, 61(8), 1678-1688.

Baba, Y., & Austin, D. M. (1989). Neighborhood environmental satisfaction, victimization, and social participation as determinants of perceived neighborhood safety. Environment and Behavior, 21(6), 763-780.

Heller, S. B. (2014). Summer jobs reduce violence among disadvantaged youth. Science, 346(6214), 1219-1223.

Gelber, A., Isen, A., & Kessler, J. B. (2014). The effects of youth employment: Evidence from New York City summer youth employment program lotteries (No.20810). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bergman, A. B., Rivara, F. P., Richards, D. D., & Rogers, L. W. (1990). The Seattle children’s bicycle helmet campaign. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 144(6), 727-731.

University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. (2016). What Works for Health: Car seat distribution & education programs. Retrieved from http://whatworksforhealth.wisc.edu/program.php?t1=20&t2=113&t3=127&id=180.

Roa, A. & Ross, C. (2018). Planning healthy communities: Abating preventable chronic diseases. In B.A. Fiedler (Ed.) Translating national policy to improve environmental conditions impacting public health through community planning (51-77). New York: Springer International Publishing.

Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

Viveiros, J. (2015). Affordable housing’s place in health care. Washington, D.C.: National Housing Conference Center for Housing Policy: Ideas for Housing Policy and Practice.

Turner, M.A., Greene, S., Scally, C.P., Reynolds, K., & Choi, J. (2019). What would it take to ensure quality, affordable housing for all in communities of opportunity? Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute: Catalyst Brief.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). Nevada and Idaho Are the Nation’s Fastest-Growing States. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/estimates-national-state.html

U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). 2013-2017 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/news/updates/2018.html

Health Improvement Organization. (2013). Community action plan 2013-2020. Health Improvement Organization.

Ibid.

Cole, B. L., MacLeod, K. E., & Spriggs, R. (2019). Health impact assessment of transportation projects and policies: living up to aims of advancing population health and health equity? Annual Review of Public Health.

Fraze, T., Lewis, V. A., Rodriguez, H. P., & Fisher, E. S. (2016). Housing, transportation, and food: how ACOs seek to improve population health by addressing nonmedical needs of patients. Health Affairs, 35(11), 2109–2115.

Lee, R. J., & Sener, I. N. (2016). Transportation planning and quality of life: Where do they intersect? Transport Policy, 48, 146–155.

Litman, T. (2007). Developing indicators for comprehensive and sustainable transport planning. Transportation Research Record, 2017(1), 10–15.

Mueller, N., Rojas-Rueda, D., Cole-Hunter, T., de Nazelle, A., Dons, E., Gerike, R., … Nieuwenhuijsen, M. (2015). Health impact assessment of active transportation: a systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 76, 103–114.

Ayala, G. X., & Elder, J. P. (2011). Qualitative methods to ensure acceptability of behavioral and social interventions to the target population. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 71, S69-S79.

Zatzick, D. F., Koepsell, T., & Rivara, F. P. (2009). Using target population specification, effect size, and reach to estimate and compare the population impact of two PTSD preventive interventions. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 72(4), 346-359.

Adler, N. E., Cutler, D. M., Jonathan, J. E., Galea, S., Glymour, M., Koh, H. K., & Satcher, D. (2016). Addressing social determinants of health and health disparities. Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative: National Academy of Medicine Perspectives.

Paluck, E. L., Shepherd, H., & Aronow, P. M. (2016). Changing climates of conflict: A social network experiment in 56 schools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 566-571.

Amanor-Boadu, V. (2003). Assessing the feasibility of business propositions. Department of Agricultural Economics Agricultural Marketing Resource Center, Kansas State University.