Emma Channpraseut, Lucy Jacobsen, Romi Bekeris, Carl Cordova

Dr. Mari Rice (Ed. D) – ENVSTD 300

Land Trust of the Treasure Valley

Introduction

Learning Goals:

By partnering with the Land Trust of the Treasure Valley (LTTV) and the City of Boise to complete a hands-on-service-learning project, our class worked directly under Stewardship Coordinator Madison Skinner and Martha Brabec to gain experience restoring native ecosystems, learn how various stakeholders prioritize environmental issues, develop collaboration skills in a community setting, and advance our understanding of land management and ethics.

Community Partner: Land Trust of the Treasure Valley (LTTV)

Mission Statement:

LTTV is a nonprofit dedicated to balancing growth & land protection. For over 25 years, they have worked to conserve the Treasure Valley Open Spaces by working with landowners, developers, government agencies and citizens to protect surrounding lands for generations to come.

Project Purpose/Community Identified Need:

Preservation of our open spaces are important for the Treasure Valley community. LTTV exists to:

- Protect wildlife habitats and waterways

- Increase conservation of private and public lands

- Mitigation the effects of climate change and preventing damage

- Foster Community education and culture of conservation

Course Concepts

Applied course concepts:

Restoration Islands: A restoration method that includes small-scale planting of desired native species in strategic locations

Adaptive Management: A process to assess, design, implement, monitor, evaluate, and adjust management as it progresses

Designed Experiments: Experiments that ecologists design in order to test the effectiveness of different alternative approaches within a restoration project

Tragedy of the Commons: a concept explained by Garrett Hardin as when public lands and resources are overexploited by public use

Land Ethics: we focused on 4 main land ethic models proposed by Jedediah Purdy, with this project primarily focusing on Progressive Management and Ecological Interdependence

Our experience with the restoration project supported our learning on all of these class concepts. While individually we all may have had different land ethics through which to view our work, our partnership with the LTTV best exemplified the progressive management approach to restoration.

Reflection

This service-learning opportunity gave our class the chance to apply ourselves as both students and stakeholders of the environment in a project meaningful to the land and people. We were able to practice and embody the different environmental ethics and perspectives we have been learning about in ENVSTD 300, understanding how our mindsets fit into previous frameworks such as progressive management or ecological interdependence, while tackling a tragedy of the commons issue we learned about.

While each of us came away from this project with different reflections and new understandings of Hillside to Hollow, our teamwork as a class affirmed our recent learning on the importance of community collaboration. Without the support of others, land restoration not only feels impossible, but could face setbacks by land users that don’t agree with restoration changes. When land users feel informed, they are more likely to understand the importance of restoration work in recreational areas, so it was great that our class along with Land Trust partners were able to work together on the land while also educating trail users on our work.

We were also surprised by the amount of wildlife already growing and ever increasing within the restoration island where we weeded, planted, and fenced. We found a variety of insects, arachnids, native plants, animal burrows, and heard various bird songs during our work. It became increasingly clear to our class that the lands of Harrison to Hollow are not only valued by recreationists, but are also deeply valued as a home by local wildlife. As the sagebrush ecosystem continues to decline, the availability of sagebrush to endemic species becomes even more important to foster on the land.

Methods

The restoration project was completed in four site visits, each with a designated goal:

- Weeding and fence building

- Fence building and reinforcement

- Raking, weeding, planting, and watering

- Planting, mulching, and watering

Results

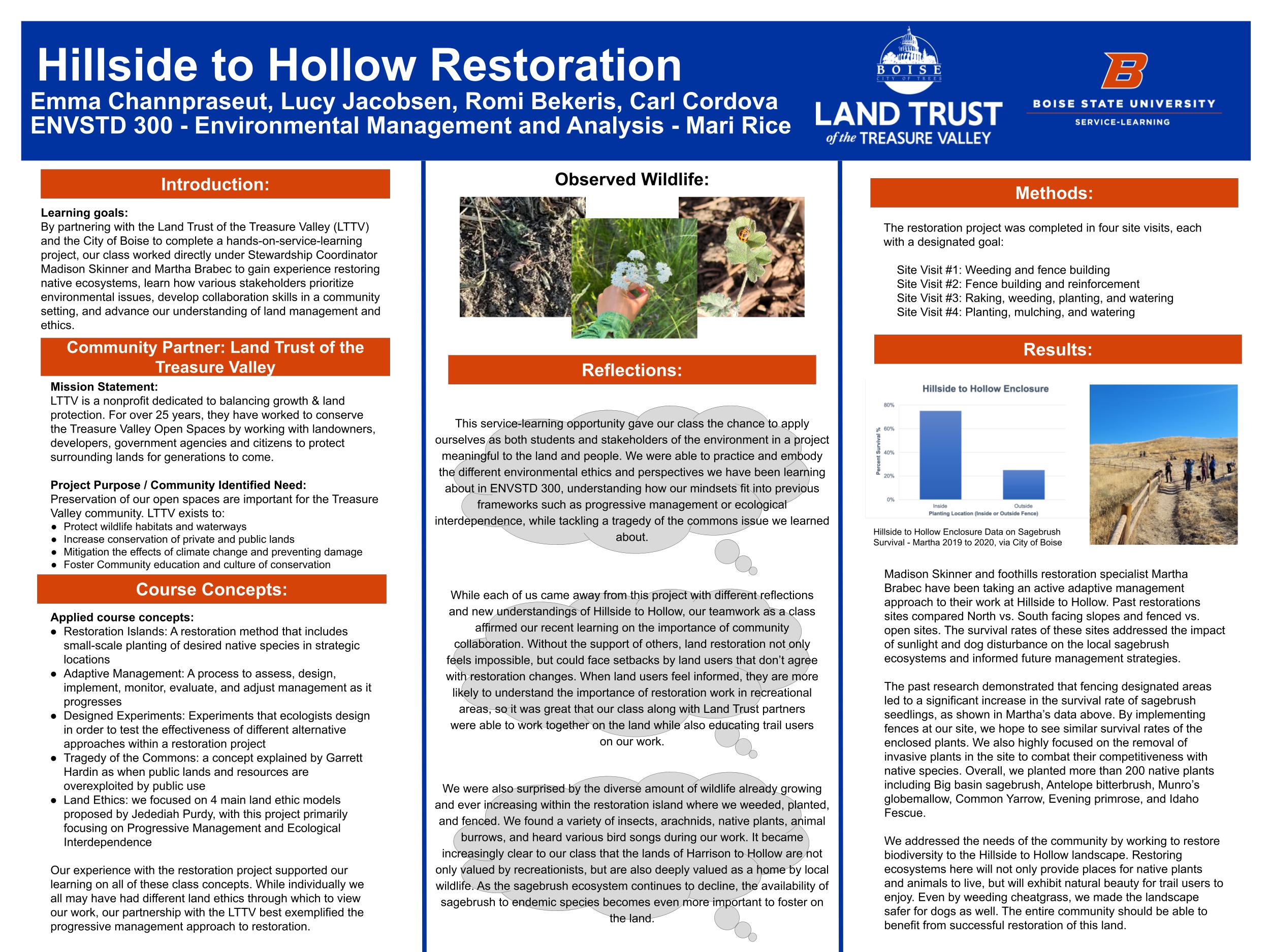

Madison Skinner and foothills restoration specialist Martha Brabec have been taking an active adaptive management approach to their work at Hillside to Hollow. Past restorations sites compared North vs. South facing slopes and fenced vs. open sites. The survival rates of these sites addressed the impact of sunlight and dog disturbance on the local sagebrush ecosystems and informed future management strategies.

The past research demonstrated that fencing designated areas led to a significant increase in the survival rate of sagebrush seedlings, as shown in Martha’s data above. By implementing fences at our site, we hope to see similar survival rates of the enclosed plants. We also highly focused on the removal of invasive plants in the site to combat their competitiveness with native species. Overall, we planted more than 200 native plants including Big basin sagebrush, Antelope bitterbrush, Munro’s globemallow, Common Yarrow, Evening primrose, and Idaho Fescue.

We addressed the needs of the community by working to restore biodiversity to the Hillside to Hollow landscape. Restoring ecosystems here will not only provide places for native plants and animals to live, but will exhibit natural beauty for trail users to enjoy. Even by weeding cheatgrass, we made the landscape safer for dogs as well. The entire community should be able to benefit from successful restoration of this land.