While most Boise State students took a well-deserved break over the summer, Chase Franklin was hard at work continuing his studies. He spent nine weeks from June to August at the Translational AI Center at Iowa State University, getting hands-on experience with AI in agriculture and developing innovative technology solutions.

Blending art and technology

Franklin wasn’t always working on AI. He started his Boise State career as an electrical engineering major. It fit well with his love of tinkering and his affinity for technical work, but electrical engineering wasn’t as fulfilling as he’d hoped.

“There was a gap between what I was doing and what I wanted to do,” Franklin said. He had a creative side that electrical engineering wasn’t satisfying, and he started to burn out after three semesters in that program.

The solution came from a School of the Arts program he heard about through some friends: Games, Interactive Media and Mobile Technology (GIMM).

“GIMM is a place where I really felt like I’ve thrived,” he said. “Instead of spreading myself thin across my creative outlets and my course work, I can fully dedicate myself to GIMM which incorporates both the technical and creative challenges I need.”

This is a relatively new program at Boise State. Founded in 2016, GIMM teaches students to use cutting-edge technology to create experiences. Its students take classes in everything from video game design to the “Internet of Things,” preparing them for careers as game developers, web developers and more.

The program was a natural match for Franklin. It gave him the chance to flex his creative muscles while building the technical skills he needed to push his horizons.

Impact through innovation

Franklin arrived in Iowa earlier this summer to work at the Translational AI Center. “The professors didn’t quite know what to do with me,” he admitted, “and that’s the place I like to be.”

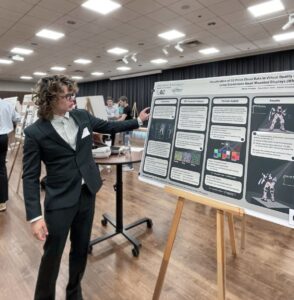

He took full advantage of this freedom to explore the work going on there – deploying AI and computer vision technology for agriculture – while pursuing his own project, a new way of rendering 3D objects in virtual reality and other platforms.

The ability to scan and render 3D objects is the new frontier for VR with implications for other fields. Archeologists could use it to scan and study delicate artifacts in immaculate detail. Video game designers and movie directors could add real-world objects to their digital worlds. Fast, accurate 3D rendering could change the way we experience virtual reality.

No matter who uses 3D scans and for what purposes, modern scanning technologies all have one thing in common: they use lasers or imaging technology to generate point clouds, millions of data points that represent physical objects in the virtual world.

But detailed point clouds demand powerful hardware to render 3D objects in real-time. Common household devices like VR headsets and phones don’t have the processing power to chew through them.

That’s where Franklin’s work comes in.

He woke up one morning with an epiphany: he could use the red, green and blue (RGB) color channels in graphics hardware to smuggle point cloud data in. These graphics processing units (GPUs) are already built to speedily render computer images, but without Franklin’s innovation, they aren’t optimized to handle point clouds.

During testing at Iowa State, his method rendered complex 3D objects at over 70 frames per second on popular VR headsets, like Meta’s Quest 3. For comparison, 60 frames per second is considered excellent for most 2D video applications.

Franklin has one year left in Boise State’s GIMM program. He then plans to pursue a Ph.D., something his professors and the Translational AI Center have prepared him for.