Submissions in the research category are open to research topics in any field: STEM, Social Sciences, Business, Humanities, etc. Submissions should use the documentation style appropriate to the discipline and should not exceed 20 pages. Lorena Alvarado wrote the 2nd place submission in the Research category for the 2025 President’s Writing Awards.

About Lorena

My name is Lorena, and I’m a fourth-year undergrad majoring in Narrative Arts. I’ve loved writing since middle school, and with my major I’ve been so lucky to figure out my passions as a writer and continue growing as a creative. I’ve been able to dabble in play writing, screenwriting and film work, and literature courses. I’m a fiction writer at heart, though, and I’d love to one day publish my fantasy series that are currently in the works. I’m also a consultant at the university’s Writing Center and love being able to help others flourish as writers. Outside of writing and school, you can find me buying books I don’t need, watching cartoons instead of reading those books, and drinking overpriced lattes. I’m very grateful and excited to have gotten this award; thank you for taking the time to read my essay, and I hope you enjoy it!

Winning Manuscript – AI as Bullshit: Art, Artists, and Human Connection

Art is something that is made by humans, for humans, interweaving the lives of artist and audience in an unparalleled manner. This can be seen in countless different ways—and, in one example, through modern-day musicians’ relationships with their audiences. Indie musician Ricky Montgomery—who became particularly well known through social media app TikTok— went on tour in North America and Europe with a string of sold-out shows in his wake. In the caption of a TikTok video he posted March 21, 2024, Montgomery recounts a one of these shows during which the audience held up paper fish during one of his songs, “Black Fins”. The song was written about the death of Montgomery’s father, and the emotional aftermath after he “ran away to Mexico during a manic episode and turned up dead after disappearing for a few weeks” (Montgomery). Montgomery goes on to write that:

Last year, I finally went to that part of Mexico to make a video about it. it was a really hard thing to write about, and even harder to tell the world about. But I believe that stories like mine are not as rare as they seem, and since I put out the song, many people have reached out to share their stories with me. the song itself was not very successful, probably because it’s a bummer. But I’m proud of myself for making it despite the commercial risk.

He took an extremely personal story and turned it to art, not for monetary purposes—in fact, he admits the song to have been “not very successful” and a “commercial risk”—but rather for the purpose of expressing his feelings about his late father. While this in and of itself is a rich example of art for the sake of human connection, it goes further: the fan project with the paper fish was not the first project to be exacted at a Montgomery concert, but it “was the first time I almost cried because of one” (Montgomery). Montgomery ends his caption on acknowledging his own fanbase’s impact on himself, as well as the emotional connection formed between artist and audience through performance:

You always hear stories about how “tiktok artists” play shows and the crowds only know “the viral ones.” Maybe that’s true for some people. And that’s sad. But my shows aren’t like that. and it’s spontaneous moments like this one that remind me how unbelievably lucky I am to have the fans that I have. They aren’t just tiktok fans, they aren’t just anime fans. They are real, deep people with their own rich lives and, at the shows, our stories get to intersect for a few hours. And that experience is one of the things I cherish the most about live music and performance in general. Go out and see a show sometime, even if it isn’t mine. You won’t regret it.

The impact of art is a cycle: an artist produces often-heartfelt art, audiences are touched, and that emotion is given back to the one who made it. Montgomery operates as an artist without bullshit: his work is not to shape audience perceptions of him, but rather to create art simply for art’s sake and to evoke genuine emotion from himself and his listeners.

While this should be the behavior behind any creative endeavor, in the current modern age, the use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has recently boomed within the art world. This has created mixed responses, though many—artists in particular—have been outwardly opposed to it. As it is, the use of artificial intelligence will not stop, and its use already spans across many different areas of life. While AI can—and even should—be used as a tool of creation, there must be a limit. Art fosters connectedness between artist and audience. It is a medium created by humans for humans that AI should not interfere with. AI has no place in producing art, given that it is inaccurate, steals real artists’ work, and takes away from the unique connectedness that human-to-human art provides. As AI use only continues to grow, a stance must be taken on the use of it within art, lest AI overrun real people who may already struggle to make a living with their creations. Ultimately, AI art is bullshit and those who claim to make art with it are bullshitters—and in a realm of creativity that nurtures person-to-person interconnectedness, there is no room for bullshit.

Philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt defines bullshit by comparing it to truth and lying. In his essay “On Bullshit” he writes that “the bullshitter may not deceive us, or even intend to do so, either about the facts or about what he takes the facts to be. What he does necessarily attempt to deceive us about is his enterprise” (54). In other words, the bullshitter cares only for altering perceptions of himself, with a total disregard for truths or lies. The use of generative AI to create various types of art is, therefore, largely bullshit: Futurism—in its publication Neoscope—reports that Men’s Journal began, in 2023, putting out articles written by AI. As is often seen with AI content, its first AI-made article “was written with the confident authority of an actual expert. It sported academic-looking citations, and a disclosure at the top lent extra credibility by assuring readers that it had been ‘reviewed and fact-checked by our editorial team’” (Christian). However, like the proper bullshitter, the AI-generated article was not concerned with facts, but only seeming smart. Jon Christian of Neoscope continues, relaying that “Bradley Anawalk, the chief of medicine at the University of Washington Medical Center…reviewed the article and told Futurism that it contained persistent factual mistakes and mischaracterizations of medical science that provide readers with a profoundly warped understanding of health issues.” Clearly, this highlights an example of AI use within the world of writing—and that of fact-checking— gone awry. Men’s Journal went back and edited the paper until it was largely unrecognizable from its original version (Christian). Had genuine intentions been at the forefront of this article’s creation—rather than the bullshitter’s desire for manicured perceptions—AI would not have been so heavily relied on. There is an expectation from readers to be given factual information, particularly when coming from a health magazine. The same is true for audiences expecting genuine art from artists. AI, it has been shown, often produces bullshit, but a step back must be taken: what, exactly, is generative AI?

According to doctor of philosophy Trystan S. Geotze, many artificial intelligence programs use the work of others to generate content. Geotze writes that:

the AI involved in image generators is not ‘intelligent’ in the way that human beings or other animals are intelligent. It has no internal experience, no desires, no autonomy, and no embodiment. The term artificial intelligence is used here, as in most contemporary contexts, to refer to a complicated computational model that replicates results usually only possible through the actions of intelligent beings. (6)

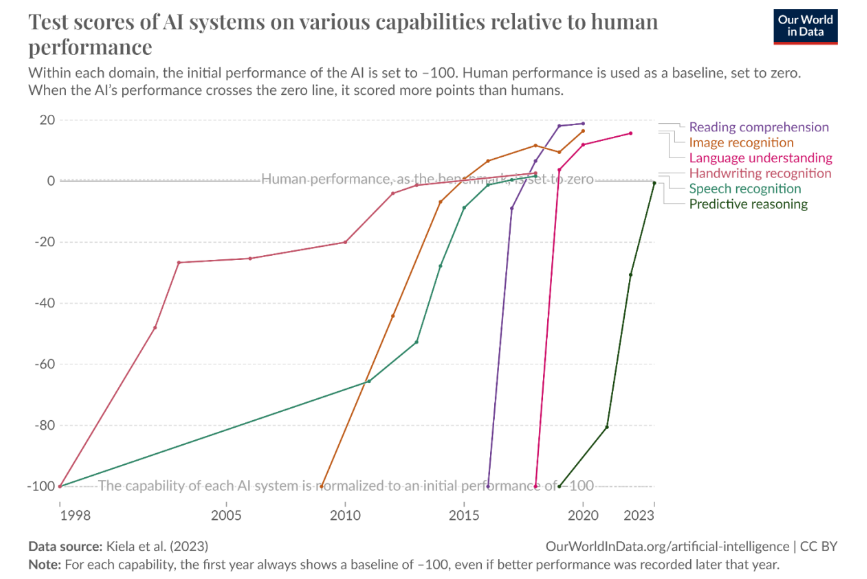

They go on to explain how it works, ultimately relaying that AI must be trained with data. It then creates a mathematical model based on things like patterns found in the training data to create its own outputs. This can be done to create written works—such as the Men’s Journal article—or image generation as well. AI’s ability to do so has skyrocketed within the last ten or so years alone—as seen in Figure 1, AI’s ability to be more accurate than people in things such as reading comprehension, image recognition, and more trumps that of humans’ by soon after 2015.

Yes, in this figure showcasing studies by Kiela et al., human performance is set at the benchmark of zero in the capabilities of reading comprehension, image recognition, language understanding, handwriting recognition, speech recognition, and predictive reasoning. The AI ability begins at -100, starting in 1998. By 2019, AI met or surpassed human capabilities in every category. This has moved forward hand in hand with AI’s generative abilities as well, as image generation has become more realistic—though of course still not perfected—throughout the years. Although, “AI systems’ ability to easily generate vast amounts of high-quality text and images could be great – if it helps us write emails…– or harmful – if it enables phishing and misinformation, and sparks incidents and controversies” (Giattino et al.). AI’s capabilities continue to grow, and with it, so does room for increased harm from it through generative art.

For image generation, AI’s training data is a large pool of images accompanied by short captions or text descriptions. A common dataset, LAISON-5B, has nearly 5 billion of these image-caption pairs. They are “collected using web scrapers, i.e. applications that crawl through the World Wide Web downloading data from publicly accessible websites” (Goetze 7). Put simply, public websites are stripped of what content is on them, and that content is used by AI to help generate its images, articles, etc. It would be safe to say that many people have posted things online—drawings, poetry, and other art forms—thinking they would be safe from this type of theft. Further, artists could have posted their works many years ago before AI was as rampant as it is now, but still remain susceptible to this “scraping” nonetheless. Due to this “scraping” of the internet, artists have spoken out against this generative AI, claiming it to be a thief of all art.

With “theft” being a broad and somewhat vague term, Goetze breaks down different types of theft (e.g., “heist” vs “plagiarism”) to find out how AI operates as a thief within each context. Goetze quotes an open letter by a group of artists asking for books and articles to avoid AI images. They write that “AI-art generators are trained on enormous datasets, containing millions upon million of copyrighted images, having harvested their creators’ knowledge, let alone compensation or consent. This is effectively the greatest art heist in history.” Lack of consent and compensation does seem to be theft—but not “heist,” as Goetze defines it as “the removal of physical artworks from their proper place without authorization” (7). As AI combs through digital works, they cannot be taken from any physical place. Goetze concludes AI art is not a heist, but other ways of thievery may still be present.

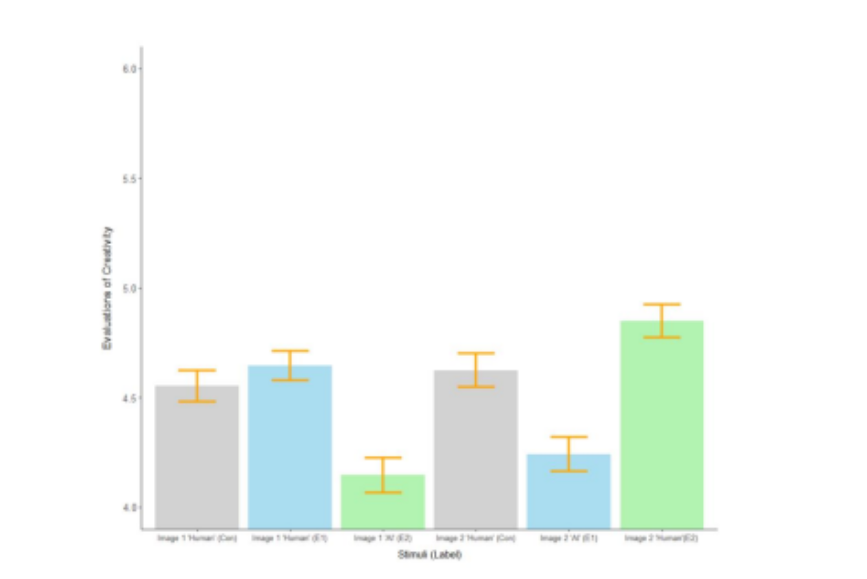

Plagiarism, Goetze writes, “is to illicitly claim creative ownership over [a creative work], that is, to assert that one is the creator of it, when in fact the work was—in whole or in significant part—created by someone else” (8). Many writers and other artists believe AI to be plagiarism. For example, AI-generated text has been banned in the r/Worldbuilding subreddit—a place of the internet dedicated to creatives sharing their fantasy work— “on the grounds that ‘AI art and writing generators tend to provide incomplete or even no proper citation for the material used to train the AI’” (Goetze 9). These feelings toward AI as plagiarism and bullshit is felt by others, and makes people devalue it and its outputs, as showcased in a 2023 study. In this study, participants were shown human- and AI-made pictures and asked, in an array of experiments with slightly differing methods, to place creative, monetary, and other types of value on each image. In the first experiment, it was found that “even though most participants reported art labeled as AI-made was largely indistinguishable from art labeled as human-made, they still evaluated art labeled as AI-made less favorably. These results suggest a general bias against AI made art” (Horton Jr et al. 2). In the fourth experiment conducted, participants (n = 789) were shown two images and were asked to evaluate their creativity:

Specifically, participants rated each painting on how creative, novel, likable, and appropriate to be sold in a gallery it was. These measures were selected based upon past research to reflect the “standard” definition of creativity in psychology which posits that ideas and objects are creative when they are perceived to be creative, novel, and appropriate to some goal…. (Horton Jr et al. 5)

When labeled as AI-made, both paintings were rated as lesser in all categories than when labeled as human-made. In fact, “the exact same painting was judged to be more creative, novel, likable, and appropriate to be sold in a gallery when it was labeled human-made and compared against an AI-made painting than when it was labeled as human-made and compared against another human-made painting” (Horton Jr et al. 5). There is a clear bias against AI art from humans; from this experiment, it has been shown that people, at least within this study, place more value on the idea of human-made material than how it looks. This goes back to Goetze’s idea that artificial intelligence cannot make art like a person due to its lack of experiences, desires, and other innately human qualities. Humans, as a social species, search for connection, and that can be found within art. The data collected from the study’s fourth experiment showcases exactly this, as shown in Figure 2.

In this figure, it is shown that all the “Human” labeled art pieces were ranked much higher in creativity. The coloring of each bar is as such:

Grey is used for the control condition (“Con”) which only contained images labeled as human-made. Blue is used for the first experimental condition (“E1”) which contained an image labeled as human-made first and an image labeled as AI-made second. Green is used for the second experimental condition (“E2”) which contained an image labeled as AI made first and an image labeled as human-made second. (Horton Jr et al. 6)

There is a clear difference between how participants felt about the innate creativity of something produced by AI versus by humans. Even though AI is capable of producing something like art, it lacks in humanness, which is heavily valued in audiences.

This humanness should be particularly valued when taking into consideration employment. Indeed, “the contemporary art world is conservatively estimated to be a $65 billion USD market that employs millions of human artists, sellers, and collectors globally” (Horton Jr et al.). What, then, could the rampant increase of AI usage in art mean for jobs? When people—particularly college students choosing their majors—set their sights on working in art, they are met with responses such as “Do you want to be a teacher?”, as if there are no other “real” options. There is a negative societal view towards careers in art, seeing it perhaps as “less than” others—and this could be due to the difficulty of getting into this type of career in the first place. Further, “historical examples from other industries provide ample evidence that, on average, automation decreases the value of human goods and labor” (Horton Jr, et al.). This could perhaps suggest that the automation of art—in the form of generative AI—could take away the value and number of human artists in the industry. Indeed, there have already been instances of artists from well-known corporations speaking out against AI.

In February 2024, the animation studio Illumination aired a commercial during the Superbowl promoting its upcoming movie, Despicable Me 4. In this commercial, the franchise’s Minion characters are shown creating AI art. The voiceover of the commercial states that, “artificial intelligence is changing the way we see the world, showing us what we never thought possible, transforming the way we do business, and bringing family and friends close together” (Illumination) as AI-made images are shown. However, each image directly contrasts what is being said, bringing forth a deliberate element of irony and satire from the makers of the commercial. As the voiceover states that AI can transform “the way we do business,” shaking hands, as depicted in Figure 3, are shown.

In this image, it is apparent immediately that this is AI-generated, as there are many extra fingers on one of the hands. The image is unsettling, furthering irony and doubt about AI’s potential to truly help in business—or any other aspect of life. As the commercial closes, the narration finishes that “with artificial intelligence, the future is in good hands,” (Illumination) before showing that Minions are generating each image. The Minions are characters widely known by modern-day movie watchers and, at that, are known to be comedic relief in the Despicable Me films. By having them being the ones to utilize AI, it becomes clear what Illumination is trying to say through their use of irony: with artificial intelligence, the future is not, by any means, in good hands. The commercial finishes by promoting Despicable Me 4 with an AI-generated—or human-made, in the inaccurate AI style—logo of the film, as shown in Figure 4.

Here, the logo for Despicable Me 4 is spelled incorrectly, the first word being “Despciable”. The lettering is wavy, as though drawn with a shaky hand. The entire commercial, all in all only 30 seconds long, pokes at the use of AI both in art and at large, showcasing its inaccuracies and unreliability. Not only was this produced by a large animation studio, but it was so too broadcasted during the Superbowl, a time during which commercials are notoriously “better” and more well made, given that they reach an extremely large audience as it watches the football game. It can be said, then, that there are real, human animators and creative companies that are willing to take a public stance against AI, feeling it does not have a place within art, and that is something that should not go unnoticed.

However, despite these opinions, and the disadvantages AI as created in the art world, arguments for its place in the creative process persist. AI has been—and could continue to be— used as a tool to complement the work of real, human artists. Secret Invasion, a 2023 television series from Marvel Studios, utilized AI to create the opening title sequence. The show follows classic Marvel character Nick Fury as he tries to stop Skrulls, a shapeshifting alien race, from invading Earth and using their abilities to replace and pose as humans. The opening sequence of the show is deliberately off-putting, with vaguely-humanoid shapes doused in a green light associated with Skrulls, as depicted in Figure 5.

This still of the opening showcases unnervingly drawn people in green lighting staring at the viewer, hinting at the overall themes of mystery and deception to come. Indeed, this was the intention behind the use of AI art: director and executive producer of the show Ali Selim said in a discussion with magazine Polygon that, “When we reached out to the AI vendors, that was part of it — it just came right out of the shape-shifting, Skrull world identity, you know? Who did this? Who is this?” (qtd. in Millman). Selim and the creators of Secret Invasion outreached to Method Studios to create the AI-generated sequence. Soon after the first episode came out, Method released a statement on the use of AI, beginning it with:

Working on Secret Invasion, a captivating show exploring the infiltration of aliens into human society, provided an exceptional opportunity to delve into the intriguing realm of AI, specifically for creating unique character attributes and movements. Utilizing a custom AI tool for this particular element perfectly aligned with the project’s overall theme and the desired aesthetic. (qtd. in Giardina)

Near the end of the statement, Method stresses that “it is crucial to emphasize that while the AI component provided optimal results, AI is just one tool among the array of toolsets our artists used. No artists’ jobs were replaced by incorporating these new tools; instead, they complemented and assisted our creative teams” (qtd. in Giardina). Clearly, AI art was used with intention and purpose on this project. Method Studios, Selim, and Marvel at large wanted to prove a point about deception and enemies hiding in plain sight; it seems they found that AI art, with its distinctly unnerving humanistic style, was attuned to this story being told. Moreover, Method Studios acknowledged the potential loss of jobs that AI could bring forth, claiming that no real people lost jobs from the opening’s method of creation.

This is a prime example of a way in which AI-generated art can potentially be used in an ethical way: with a true artistic purpose behind it, and as a tool to aid human artists with their craft. As the world careens in the direction of increased AI use, it would be an ill use of time to try banning it or otherwise ridding it from artistic creation entirely when many are already so prescribed to the idea of utilizing it. Instead, there must be increased discussion of the ethics of artificial intelligence within art and what art means for artists, audiences, and humanity at large. If AI must be used within art creation, it should be done so as a tool in assistance to real artists, and in a way that is acknowledged in a similar fashion to its use in Secret Invasion.

Ultimately, though, AI in art should not be overused, if used at all: its purpose in Secret Invasion was to highlight the alien, inhuman aspects of the show, only furthering the notion that AI is distinctly lacking in the emotion and hard effort of human-made art. As demonstrated in the study by Horton Jr and his colleagues, people are more inclined to appreciate artwork with the knowledge that other real humans put time and true effort into it. There is a connection that sprouts from art, bringing strangers together through the mutual human tendency to create. The Ricky Montgomery concert showcases exactly how touching art can be for both artists and audiences—writing from and about personal experiences, Montgomery’s music moves fans and therefore himself. His message that fans are “real, deep people with their own rich lives and, at the shows, our stories get to intersect for a few hours,” (Montgomery) encapsulates well the power art has on human connection. The use of generative artificial intelligence continues to grow substantially, and as it does so, it must not override real people in the realm of art and creation that has been uniquely human- and community-centric. Art—as music, animation, or any other form—fosters genuine connection stemming from genuine human emotion. In that, there should be no room for bullshitting—there should be no room for the use of AI.

Works Cited

Christian, Jon. “Magazine Publishes Serious Errors in Frist AI-Generated Health Article.” Neoscope, 18 February 2023, https://futurism.com/neoscope/magazine-mens-journal errors-ai-health-article

“Despicable Me 4 – Minion Intelligence (Big Game Spot).” YouTube, uploaded by Illumination, 11 February 2024, https://youtu.be/SJa1oSgs8Gw?si=f2mqvcHcTmC_QSiF

Frankfurt, Harry G. On Bullshit. Princeton University Press, 2005.

Giardina, Carolyn. “‘Secret Invasion’ Opening Using AI cost ‘No Artists’ Jobs,’ Says Studio That Made It (Exclusive).” The Hollywood Reporter, 21 June 2023,

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/secret-invasion-ai-opening-1235521299/

Giattino, Charlie et al. “Artificial Intelligence.” Our World in Data, 2023, https://ourworldindata.org/artificial-intelligence

Goetze, Trystan S. “AI Art is Theft: Labour, Extraction, and Exploitation, Or, On the Dangers of Stochastic Pollocks.” 2024, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.06178

Horton, C. Blaine, Jr. et al. “Bias against AI art can enhance perceptions of human creativity.” Scientific Reports, vol. 8, no. 19001, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45202-3

Millman, Zosha. “Yes, Secret Invasion’s opening credits scene is AI-made—and here’s why.” Polygon, 22 June 2023, https://www.polygon.com/23767640/ai-mcu-secret-invasion opening-credits

Montgomery, Ricky. [@rickymontgomery]. “in san francisco recently, something…” TikTok, 21 March 2024, 16

https://www.tiktok.com/@rickymontgomery/video/7348971131212139806?is_from_web app=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7345693770812245547.

Pulliam-Moore, Charles. “Unfortunately, Secret Invasion’s AI credits are exactly what we should expect from Marvel.” The Verge. 27 June 2023,

https://www.theverge.com/2023/6/27/23770133/secret-invasion-ai-credits-marvel