When the sun sets, Idaho transforms into a stargazer’s paradise.

The Central Idaho Dark Sky Reserve, a 1,146 square mile expanse internationally recognized for pristine night skies, welcomed its first astronomer-in-residence last week.

Catherine Slaughter, a master’s student at Leiden University in the Netherlands, will live and work in the reserve for one month. With community outreach events, she hopes to share her love of astronomy with the public.

The program is part of a $1 million NASA grant received by Boise State University assistant physics professor Brian Jackson.

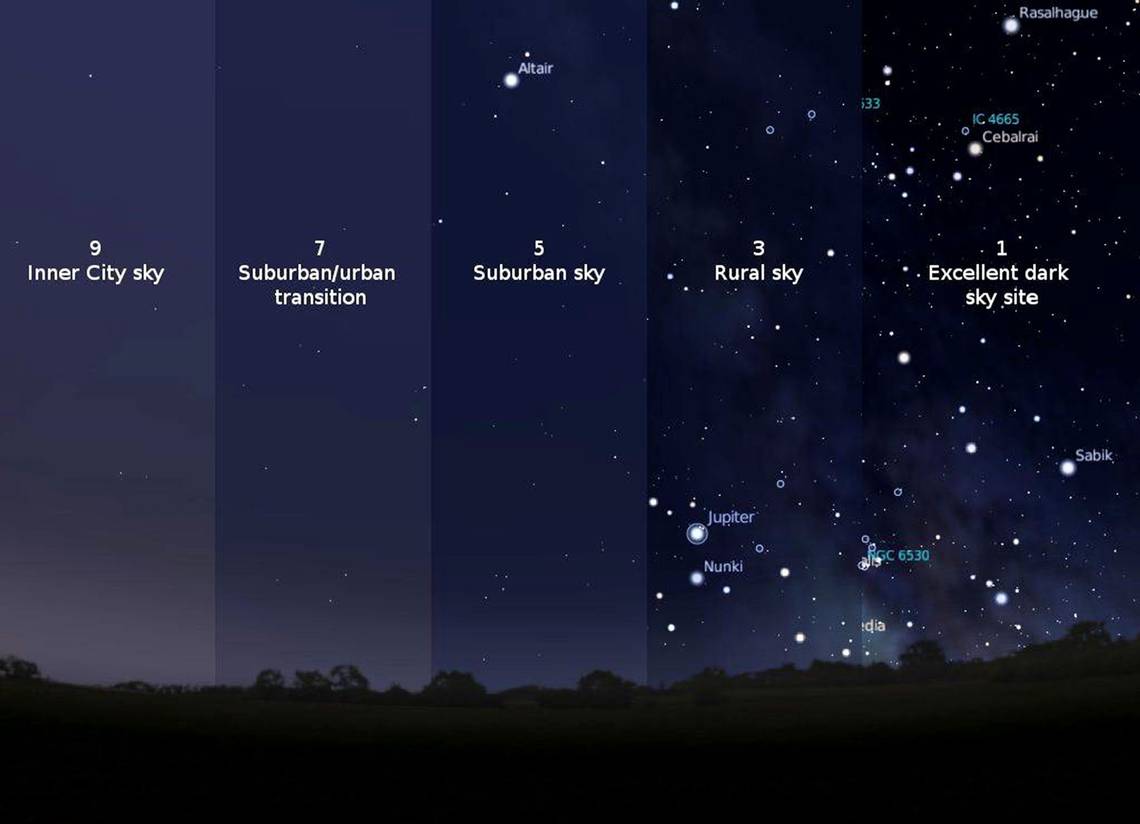

Idaho is a state that struggles with educational resources, Jackson said. But with the advantage of world-class dark skies, Idahoans can stargaze and do amateur astronomy in ways that are “essentially impossible” in other parts of the country. That’s what makes astronomy outreach in the state so important, he added.

Jackson envisioned the program last summer, thinking that a partnership between the reserve and an astronomer could spark excitement about space science.

He applied for NASA’s Science Activation program and earned funding for more than just the astronomer-in-residence program. The grant, distributed over three years, supports an astronomy outreach training program at Boise State and light pollution research at the reserve.

A SUMMER OF SPACE SCIENCE

Rugged and remote, the reserve sits in the Sawtooth National Forest and encompasses the towns of Sun Valley, Ketchum and Stanley.

As astronomer-in-residence, Slaughter will be traveling throughout the reserve to hold outreach events. She plans to lecture on topics such as indigenous astronomy, and she will be holding solar observing events, demonstrating how to find sunspots and other structures on the sun’s surface with a solar telescope. The events are geared towards people of all ages, she said.

Slaughter will also work with two “light pollution ambassadors” — UCLA undergraduates — to monitor light levels at the reserve, as excess light pollution can threaten the reserve’s dark sky status.

The ambassadorship is another new initiative funded by Jackson’s NASA grant. Trained by Travis Longcore, associate adjunct professor at the UCLA Institute of Environment and Sustainability, the two students will collect data with a “sky quality camera.”

A sky quality camera uses a fish-eye lens pointed upwards to measure the amount of light in the sky, simulating how people see the night sky from the ground.

This “on-the-ground” data is a useful addition to remotely collected data: satellite images. While satellite data can show light levels across large areas, it has limitations, such as not being able to capture blue light, Longcore explained.

Blue light scatters farther than other colors and is often used in new lighting technology, Longcore added. Combined, the two data sources will paint a more accurate picture of light levels at the reserve.

Light pollution ambassador Jules de la Cruz is an incoming senior at UCLA. Born and raised in Los Angeles, she’s never experienced dark skies.

“I don’t think I actually know what darkness is,” de la Cruz said. “I can’t even imagine it.”

DARK SKIES AND THE PEOPLE UNDERNEATH THEM

While the solutions to light pollution are not too complicated or expensive, people have to be aware of them, Jackson said.

The reserve’s residents know this well.

In the city of Stanley, all outdoor lights are dark sky compliant. Lights are projected toward the ground and avoid blue tones.

Local communities, in partnership with the Idaho Conservation League and the U.S. Forest Service, began the process to get dark sky status in 2015. Two years later, the International Dark-Sky Association awarded the reserve “Gold Tier” status, the first of its kind in the United States.

The reserve’s sky is a spectacular sight, said Stanley Mayor Steve Botti, who helped drive the push to protect Central Idaho’s night skies. “

You can see the Milky Way pretty much every night, and that draws people to the area.”

For Slaughter, it was not the Milky Way but meteors that cemented her love for the stars. She was 7 years old. Sitting on her dad’s lap in northern Michigan, she watched the Perseid meteor shower illuminate the sky.

“The reserve only exists because of the enthusiasm of the folks who live on and around it,” Slaughter said. “I’m excited to meet people and chat with them about my favorite thing in the world.”

At the end of the day, wanting to preserve dark skies is a question of what we value, Longcore said. “I find there are intrinsic reasons to preserve the night sky. It’s something that connects us to our ancestors.”

Humans throughout history have seen the same sky, and the idea that we would deny this generation the ability to see that and feel a place in the universe is tragic, Longcore added.

Perhaps astronomy outreach this summer at the Central Idaho Dark Sky Reserve will inspire Idahoans to contemplate their place among the stars.

Read more at: Constellation prize: NASA-funded astronomy expert coming to educate Idaho stargazers