Understanding participation in e-learning in organizations

Lean production, employee learning and outcomes

The motivating opportunities model for performance

Excerpt from: Chyung, S. Y. (2005). Human performance technology from Taylor’s scientific management to Gilbert’s behavior engineering model. Performance Improvement Journal, 44(1), 23-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pfi.4140440109

Although Gilbert’s model has been frequently introduced in the literature (e.g., Dean, 1997; Fuller & Farrington, 1999), his idea of “diffusion of effect” seems less frequently discussed in the literature. In his book, Gilbert explained the important principle about the diffusion of effect:

Whenever I change some condition of behavior, I may indeed—and often will—have a significant effect on some other aspect of behavior. So, if I improve the incentives for performance, people may learn more, even though I have made no effort to teach them better. And when we give people better information about their successes, we may have also improved their incentives to perform well…. There is no way to alter one condition of behavior without having at least some effect on another aspect—often, a considerable effect. And usually it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine the degree of the diffusion of the effects. (1978, p. 94)

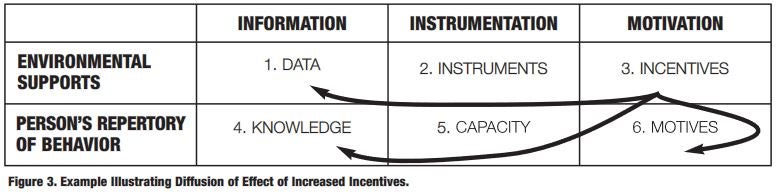

HPT practitioners should use this principle to maximize the overall effect of a selected intervention. For example, in a hypothetical situation, promising a proper level of compensation (incentives) may reduce equity tension in workers and help them feel appreciated and motivated (motives), which in turn may encourage them to pay more attention to the information required for the work (data) and become self-directed to teach themselves to be more competent performers (knowledge) (see Figure 3).

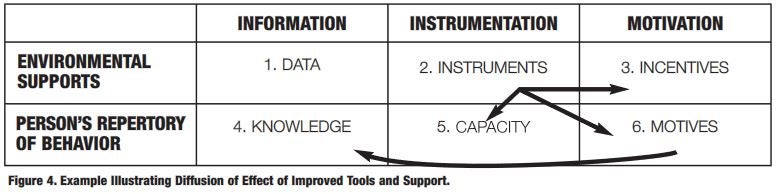

In another hypothetical situation, providing an enhanced tool and institutional support may not only increase performers’ capacity, but may also be viewed as an incentive and may change the level of motivation, encouraging performers to become more self-directed and to seek the knowledge and skills necessary to accomplish their job tasks (see Figure 4).

This is a systemic view of engineering human performance. Rothwell (1995) eloquently illustrates the need for acknowledging the side effects of human performance engineering: “Making changes in human systems is akin to bumping a single strand of a spider web. The result is that the whole web vibrates, not just the strand you touched” (p. 4). With this “big picture” of the entire system in mind, HPT practitioners are better able to avoid providing piece-meal, redundant approaches.