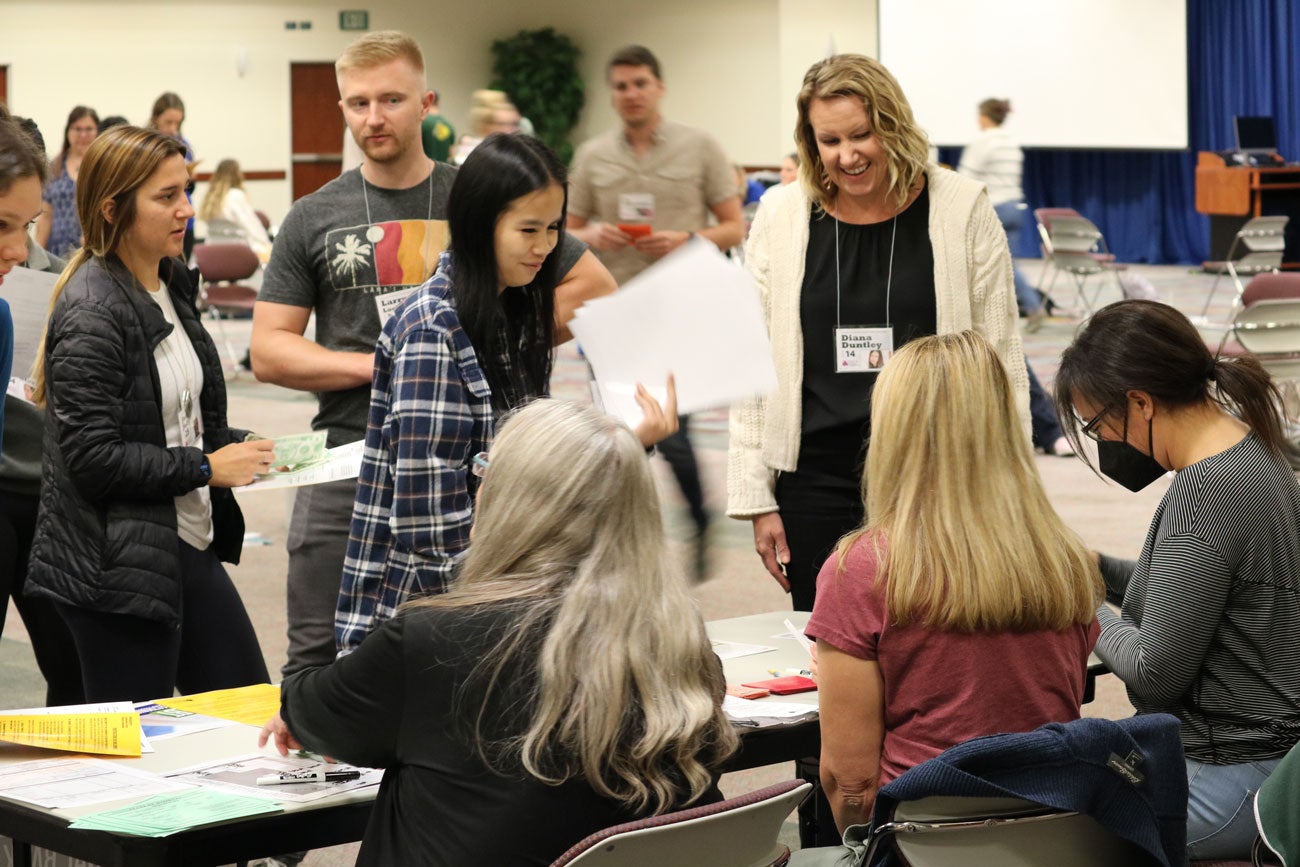

Nametag-wearing students milled around the Jordan Ballroom on Monday Sept. 19, alternating between clumps of chairs in the center of the room and tables set up around its outskirts.

But the students weren’t aimlessly wandering; they were participating in the annual Community Action Poverty Simulation.

Each year, students in their first semester of nursing courses take part in the simulation. It is designed to model a month of living in poverty in the United States through four fifteen minute “weeks”. It’s an all-hands-on-deck activity; members of the entire School of Nursing get involved from older students to staff, leadership and professors.

According to the Missouri Community Action Network, which now owns the rights to the simulation, the activity’s history roots back in the 1970s. Over the years, it’s been further “developed to raise awareness about different aspects of poverty that can lead to a discussion about the potential for change in local communities.”

Walking a month in someone else’s shoes

Upon entering the ballroom, students are randomly divided into “households” – groups of anywhere from five people to one person – and assigned to a “house” – a group of chairs in a circle.

At the beginning of the simulation, students open a packet and each don a name tag with the identity of the individual they’ll be representing. This could be anyone from an 82 year-old grandma with disabilities or an 8 year-old attending public school.

Assistant professor Sarah Llewellyn, the emcee for this year’s simulation, explained that the family units are modeled after real life individuals who are not in extreme poverty, but who are classified at the poverty line. In a technical sense, this means the annual income for a family of four is about $25,000.

The students’ task is simple: “live life” while navigating the difficulties of poverty. Children go to school, those of working age may apply for a job, and adults pay bills.

As students learned to navigate community resources like food stamps and social services, they also faced other struggles like transportation issues, robberies or eviction.

“It’s not meant to be a negative experience,”said Casey Blizzard, the simulation center operations coordinator. “Sometimes they end up with more money than they started with, but a lot of the time they are able to experience what being in poverty would feel like, when you have that feeling of just not being able to get ahead.”

Lessons learned from lessons lived

After the end of the “month”, everyone involved in the simulation – even those representing community workers, like Bankers and Social Workers – debriefs the experience. Participants shared personal reflections and mentioned what stood out to them.

They talked about the difficulty of accessing social services, such as when the office closed early on Fridays. Students would have to take a day off work and lose a day’s wages to go during a weekday. “So you can kind of understand why people may not go and access the services even if they know they’re available,” Llewellyn said.

At the end of the simulation, 12 out of the 24 families hadn’t paid their utility bills. Although it might have been excusable for the simulation, it isn’t realistic to think they’d be living in a house with no water, electricity, or gas. Llewellyn challenged the students to think about how people actually make it happen “every month, month after month after month, as these bills come in.”

“I was surprised that people still seemed stressed out even though it was a simulation,” said one of the volunteer community workers during the debrief.

“The stress in the room was palpable,” said Llewellyn. “And obviously [the simulation is] time-condensed so it pressure-cooks it a little bit more, but these are real scenarios… all based on real families.”

Applying new knowledge as future caregivers

At the simulated health center, the “doctor” revealed that only two families out of the entire “month” visited him for care, despite the fact that several simulated individuals are documented as having chronic health conditions.

Llewllyn challenged students to apply this to the real world: if nursing students, who are individuals training to focus on healthcare, overlook their own health in a simulated experience, it’s understandable that people who may not prioritize healthcare at all would have even less regard for their health in the real-life stress of poverty.

Hopefully, now armed with the knowledge of available resources and the empathy that comes from a personal experience, students will be better equipped to care for future patients living in the reality of poverty.