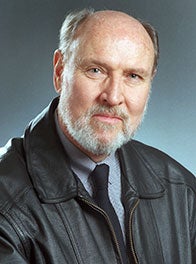

Emeritus Boise State professor Errol Jones died on Friday, April 20, at his home in the Boise Foothills.

A statement from the Department of History described Jones as “a champion of the underprivileged, a humanitarian who fought to defend people in flight from oppression, a public scholar and social progressive who never lost faith in history’s power to elevate and build.”

Jones did not want a funeral, but a “memorial toast” in his honor will take place at 2 p.m. Saturday, May 5, at the Flicks Theater, 646 W. Fulton St.

Jones earned a Ph.D. in 1971 from Texas Christian University specializing in Latin American history. From 1971-1976 he taught at the Universidad de las Amerícas in Mexico. Winner of a Latin American Teaching Fellowship for Brazil from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, he taught and did research at the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil until 1979 when he became director of the Utah History Fair at Utah State University. He joined the Department of History at Boise State in 1982. He served as department chair from 1992-1999. Jones’ many honors include receiving a Mayor’s Award for Excellence in the Field of History from the City of Boise in 2015.

Nick Miller, chair of the Department of History, called Jones a “stern but human department chair,” working “quietly but intensely with local advocates for migrant laborers and undocumented immigrants.”

Jones was the force behind Boise State’s refugee studies program and the university’s collaborative work with the city and state on refugee issues, Miller added.

For Alicia Garza, an associate professor of Spanish, Jones was a “beloved professor, top scholar of Latino history in Idaho, a dear friend of and advocate for our Mexican community.”

Fernando Mejia-Ledesma, now logistics director in Seattle for United We Dream, an organization that works on behalf of undocumented young people, was one of Jones’ students at Boise State.

“I took Professor Jones’ class on the history of Mexico. He expanded the understanding I had of Mexican history, and of my identity. Especially through the text he used, “Mexico Profundo: Reclaiming a Civilization,” that covered topics like indigenous people, colonization and genocide. It had a radical impact on the way I understood myself,” said Mejia-Ledesma.

An old-style, meticulous scholar

History Professor Todd Shallat worked with Jones for many years.

“His Boise State office desk was — is — an avalanche of historical documentation of the kind that scholars once used to piece together research back in the day when libraries purchased books and the historian’s higher calling was to contribute to the published record of human folly and misdeeds,” said Shallat. “Once we all had desks like that. Once we traveled thousands of miles to decipher yellowing scraps of handwritten correspondence. Errol published scholarship in that vein including some of the best writing we have about civil rights in Idaho. Meticulous and authoritative.”

“Everyone in our community knew Errol Jones. In his heart, he was Latino,” said Ana Maria Schachtell, a local activist. “We thought of him as a brother.”

Schachtell was the project director for “Nuestros Corridos: Latinos in Idaho, Idaho Latino History through Song and Word, 1863-2013,” a book with CDs featuring corridos, or traditional Mexican ballads written for the project. Schachtell turned to Jones to help find stories to be translated into song. Jones wrote the preface for the book and contributed his own corrido/poem about a 1935 workers’ strike in Idaho’s Teton Valley.

Here is a brief excerpt:

“The water was scarce, the land dry and quite bare

conditions so poor — there was little to share.

The summer dragged on and the place was a sight

the workers now knew that to live they must fight.”

Jones “called the Mexican worker a hero,” said Schachtell. “He shone a light on their contributions. Everyone needs to know that history, a history that has so often been ignored.

Above all, a teacher

The Boise City Department of Arts and History featured Jones in its Creators, Makers and Doers blog in 2015, the year Jones won the top cultural award given by the city. The interviewer asked Jones about what he considered the greatest success of his career. It wasn’t in publishing, or in other accolades.

Jones said, “I do think that more than anything is the fact that I taught at several universities and here at BSU for the longest period of time, and I think I reached some people and helped them grow and mature intellectually. I am pretty proud of that. I think that moving in a direction … towards teaching and researching about the Mexican people in our population, I was able to open up a window and make considerable progress on the topic. That is the most enduring achievement that I have had and I am still not through with that work.”