The ‘field lab’ for many Boise State geoscience students and faculty is often in the most extraordinary places, like the side of a volcano or along the walls of the Grand Canyon.

Now, Bronco doctoral geosciences student Jess Sorsen can stake claim to what might be the coolest and most unexpected field site for her research: nearly two miles deep in the South Pacific in the submersible that was pivotal to locating the RMS Titanic.

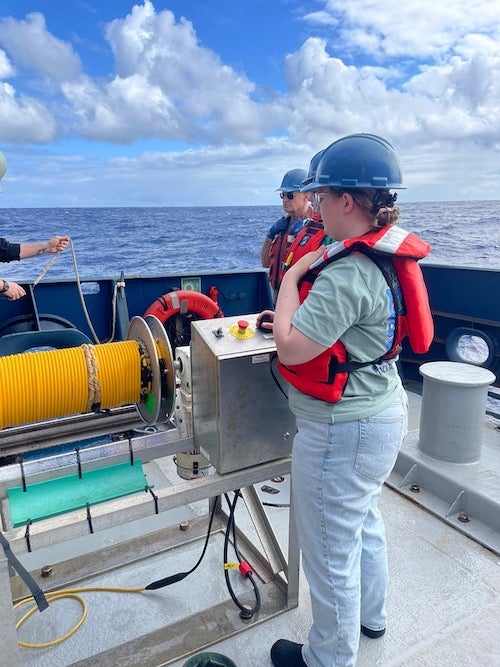

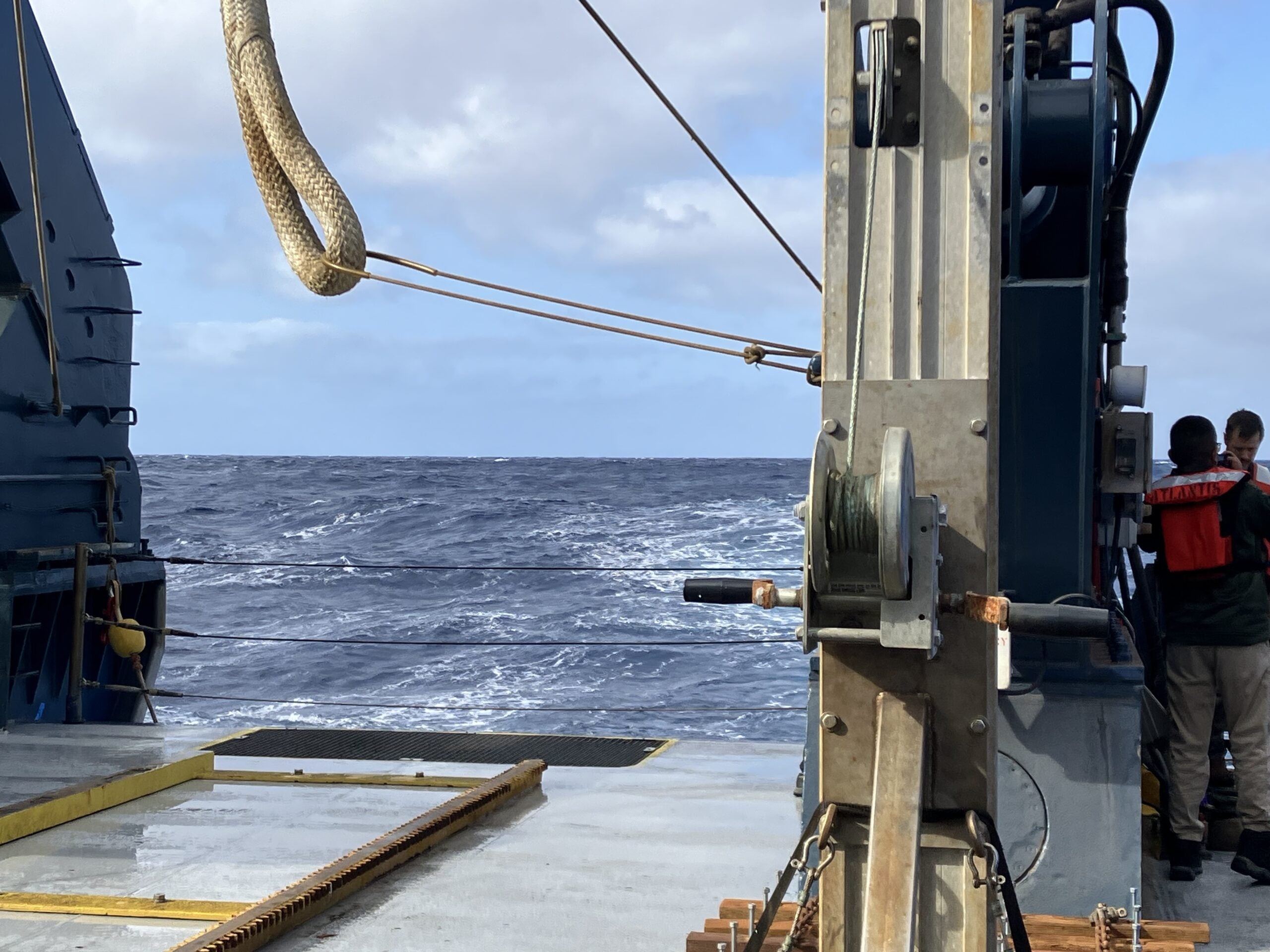

Sorsen, as well as post-doctoral research fellow Janine Andrys and geosciences technician Darin Schwartz, journeyed to collect deep-sea samples as part of a research team including the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). On a Global Class Research Vessel called the R/V Atlantis, they voyaged for a month and a half to the East Pacific Rise.

Then they conducted multiple geologic sample collections from a site on the seabed 2769 meters deep, using Human Occupied Vehicle (HOV) Alvin. Based at WHOI, the Alvin Group is funded by the National Science Foundation, U.S. Navy and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Alvin is the only publicly funded, human-occupied vehicle available to the U.S. scientific community for exploring the abyssal region in-person.

After returning from her adventure, Sorsen sat down with Boise State’s Brianne Phillips to answer all of her deep (sea) questions.

Q and A with Jess Sorsen

Q: What was it like being inside the submersible?

“We practiced going into the submersible first while it was docked, and then we got fit for oxygen masks for emergencies. We had to wear all wool clothing (because they are fire resistant). Then when we went into the submersible, we had to go up a yellow staircase and then crawl into it which was nerve wracking; it was more spacious than I thought it was going to be. I was in it for six hours, but the time flew by. A lot of people say it’s like a time machine. You go down and you come back up and it’s nighttime!”

Q: You shared some beautiful moments from your dive on the research team’s blog.

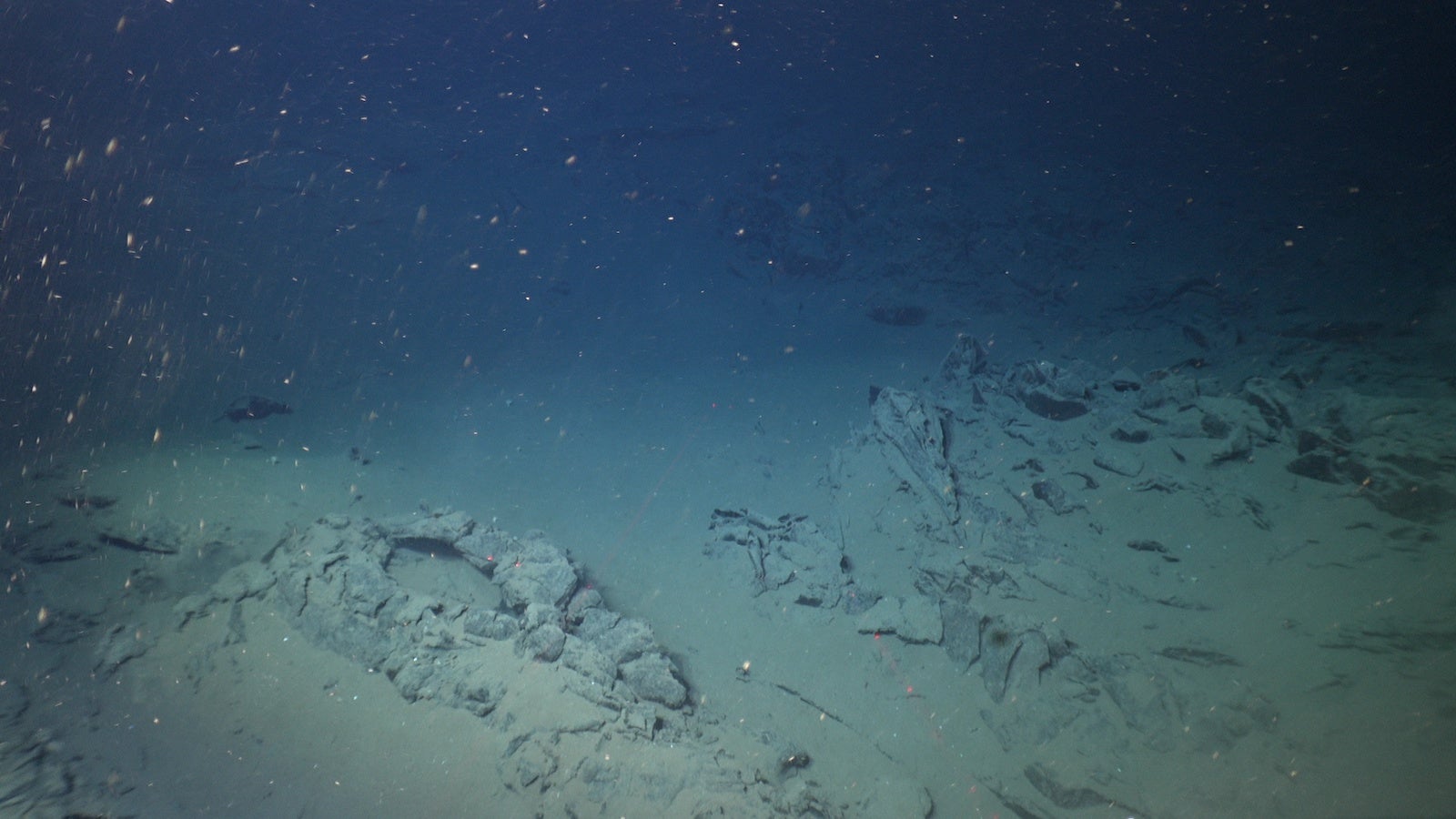

“Once the lights were turned on I spotted my first deep ocean rocks, pillow basalts. They looked like they were squeezed out of a tube of toothpaste. I spotted tons of sea life at the bottom: purple sea cucumbers, starfish, tripod fish (my personal favorite find), white coral, and a white ribbon slug. The entire time I felt like I was getting a glimpse of another world entirely.”

To learn more about team’s experience, visit their interactive map and blog .

Q: What was it like being on the R/V Atlantis and meeting with fellow scientists and ship’s crew members?

“I was impressed by all of them. Julie Bowles was supportive; she was the lead of our science party. I also got to meet Jeffrey Gee. He is a retired scientist that had been to this area in the 90s, and he was back for this project, which was really exciting. The captain came down and introduced himself to us personally, and so did the first, second and third mates, which was really cool. We were allowed in the bridge and you could see everything that was going on. Each mate would describe how they were navigating the ship and how everything works.

Q: What kind of samples did you collect and why?

We collected basalt samples so that we can study the elements and their concentration in order to understand what’s actually happening down in the Earth’s mantle.

Q: Were you able to collect many samples?

We didn’t get to collect as many samples as we would’ve liked because of the weather (trade winds) and sharks. We had a whole swarm of Whitetip Pelagic Sharks (also known as Oceanic Whitetip Sharks) and that was dangerous because swimmers were going out to detach the submarine [from the crane arm]. White tipped pelagic sharks are very dangerous, they are one of the more aggressive types.”

Q: What are the next steps for the samples you collected from the sea floor?

“I still have more samples that are on their way here from San Diego. I suspended some obsidian from the samples into pucks of epoxy on the ship and Darin brought those back in his luggage. So, I’ve been grinding away to expose the samples to run them through the electron microprobe. We’re shooting electrons directly into the sample and those electrons will bounce off different electrons in the sample’s elements (we expect mostly magnesium).

The ultimate goal for this project is to compare geochemistry (the study of the distribution of chemical elements in geological samples) with paleomagnetism (the study of the ancient magnetism of rocks) and see if we can find a correlation between the two that could create new observations.”

Q: What’s one moment from the ship that you will always remember?

“We did a ceremony for crossing the equator. People who haven’t crossed the equator on a ship before are called Pollywogs, and the people who have done it before are called Shellbacks. This is a whole tradition with seafaring. So we crossed the equator and we had a ceremony. It was really fun. I’ll get a tattoo to remember that.”

This collaborative research experience was made possible by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and NSF award: 2128091 investigated by Boise State professor Dorsey Wanless, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee professor Julie Bowles, and Scripps Institution of Oceanography professors Jeffrey Gee and Ross Parnell-Turner.