Idaho’s wool industry reached its peak during World War I when 3.2 million head of sheep roamed the landscape. To visualize that number, consider that Idaho’s current human population is around 2 million. The industry required a massive workforce.

Young Basque men looking to improve their economic status answered the call and began emigrating to the U.S. in the 1880s. They became sheepherders, a profession that required long, solitary hours in remote places.

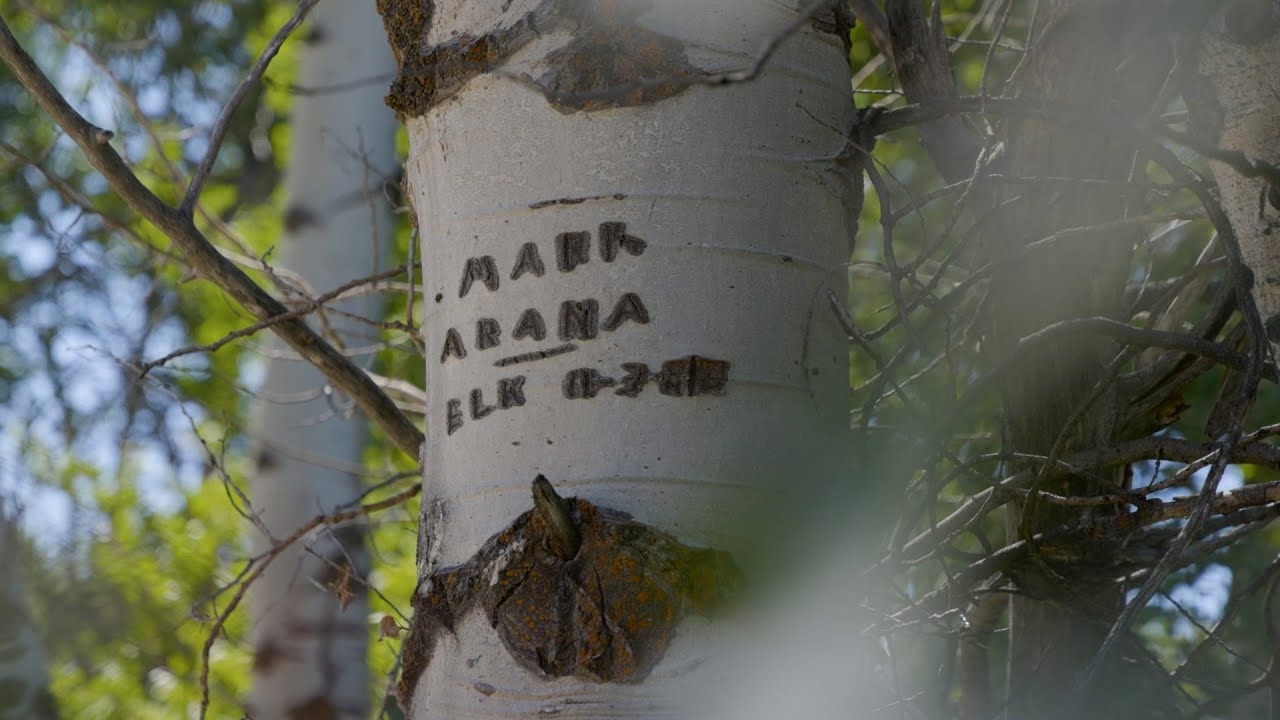

To pass the time, to leave their mark, to share political and religious beliefs, poetry, longings for loved ones and hometowns, sheepherders made tree carvings known as “arborglyphs” (arbor = tree, glyph = symbol) in the soft bark of aspen trees.

Video: Speaking Through the Aspens

Video has closed captions and a transcript is provided at the end of this page.

For the past two decades, John Bieter, a professor of history, a descendant of Basque immigrants and the son of Pat Bieter, who established the Basque Studies program at Boise State in the 1970s, has searched for Basque arborglyphs. He has cataloged thousands.

These carvings hold special interest for scholars of Basque culture and history. They connect us, Bieter said, to immigrants who came to the U.S. and worked, helping produce the clothes we wore and the food we ate, but who did so anonymously. The arborglyphs are a way to illuminate some of those immigrants’ stories, Bieter said. “As we all get curious about our pasts and want to know where we come from, this is one more opportunity.”

Bieter created the Arborglyph Collective, a Boise State partnership with the University of Nevada, Reno, and California State University, Bakersfield, fellow universities known for their Basque Studies programs. Arborglyphs exist across the West, making collaboration among academic institutions vital, said Iñaki Arrieta Baro, head of the Jon Bilbao Basque Library at University of Nevada, Reno. The phenomenon of arborglyphs is not currently well known in the Basque Country, but as European interest in the Basque diaspora grows, so will the importance of arborglyphs, he added.

The collective received a grant in 2023 from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to develop a protocol for documenting the carvings with a goal to create a public arborglyph database.

The work is urgent because the lifespan of an aspen is less than 100 years, and many of the oldest carvings have already disappeared. Increasing temperatures and wildfires present additional challenges. The source of arborglyphs has also changed. Most of the sheepherders making carvings today are Peruvians. Basque immigration and sheepherding waned in the 1980s when economic conditions improved in the Basque Country. But Bieter and others are documenting those carvings, too.

“We’re trying to document as much as we can as soon as we can,” Bieter said.John Bieter

John Bieter credits writer and academic Joxe Mallea-Olaetxe with beginning the study of arborglyphs in the U.S. Mallea cataloged over 20,000 carvings and is author of the book “Speaking Through the Aspens.”

The grant will support the Arborglyph Collective as it builds a network of history organizations with an interest in arborglyphs, many in underserved communities. Professor Cheryl Oestreicher, head of Special Collections and Archives at Albertsons Library at Boise State, is working with Bieter on this and several other parts of the project. Boise State’s digital collection of arborglyphs is available at Albertsons Library.

For a Basque American like Bieter, arborglyphs carry profound poignancy. “When I think about those sheepherders, 15 or 16 years old, some of them, with little education, not speaking the language. Coming from the Basque Country was like coming from Mars. What an experience. It’s meaningful for me to put myself in their shoes. Standing in front of an arborglyph, you are sometimes literally standing in their footprints.”

By Anna Webb

Video Transcript

(birdsong)

(light acoustic music)

[John Bieter, Professor, History Department, Boise State University]: An arborglyph is a carving in a tree. Over 90% of the time in aspens because it’s a soft bark that herders did when they had time.

[John] We are 28 miles outside of Mountain Home. We are in a grove of aspen trees. When I say we, I mean this Arborglyph Collective, this collaborative that we’ve created with three institutions: so Boise State University, University of Nevada, Reno, California State University, Bakersfield. So we have representatives, those are the ones that pooled together to do this planning grant of about this research. We are trying to do this for a larger public. So eventually the hope is to create some kind of app that those that like to hike and are out, mountain bike or whatever, and stumble across something like this could just go, oh yeah, I know how to do this. They could plug it in. That information would then go to a central database. And so we’re going to capture as many of the arborglyphs as we can.

[John] Overwhelmingly, the ones that we are tracking are sheepherders. Idaho had an enormous number of sheep. The peak during World War 1, 3.2 million head of sheep, which means you need a very, very large labor force. Basques saw this as an opportunity, and so sheepherders began to trail sheep all around Idaho, especially along the Snake River Valley. And as they’re going, stop, they see camp spots where they might be able to graze sheep for a few days, and then that’s the time when they tended to do the carving. But as the Basques left, Peruvians came behind them and we’re seeing them do the same kinds of carvings as the Basques did then.

[John] Aspens, number one, don’t have a very long life, maybe 60 to 80 years. There are some that are 100 plus, but that’s kind of a window, so we say we’ve lost probably the vast majority of those earlier ones. The challenge and the increasing challenge is just the heat and fires that are getting larger and larger. And so as climate change continues, the threat of fire becomes even more drastic, and that’s why we’re trying to document, as much as we can as soon as we can. Like I tell my students, they didn’t take selfies, you know, they didn’t do videos, they didn’t do TikTok. Hidden Language They used what they had, which are trees. They’re speaking through the aspens. It’s a hidden language of the trees. And so what we’re trying to do is to see, what is the tree, what is the arborglyph, what is it saying to us about that person, about that time, about what was on their minds? It gives us a little glimpse into really a pretty anonymous and unknown immigrant, which is often the case of immigrants. And the arborglyphs, and these I think, are a way to take that anonymity and bring them to the forefront a little bit, tell a little bit about their story. Provide opportunities for subsequent generations to be able to connect back to a grandparent, an uncle, an aunt, somebody that we know went to America, but they don’t really know their story from there. And as we all get curious about our past and want to know where we come from, this is one more opportunity, I think, to make those kinds of connections.

(birdsong)

(light music)