The discovery of gold first attracted Chinese miners to Idaho in the 1860s. In the decades that followed, thousands of Chinese men worked to build America’s transcontinental railroad, including the Oregon Short Line across Southern Idaho that later became the Union Pacific. Working conditions were notoriously poor. Chinese immigrants were overworked, underpaid and discriminated against. Many railway workers died. Among them was a Chinese man, his name now lost, who died in the 1880s near King Hill, outside Glenns Ferry, Idaho. Someone marked the site with a memorial stone beside the tracks.

A combination of weather, vandalism, a relocation and even a train derailment took its toll on the site, breaking the stone into pieces and wearing the man’s name off its face. But thanks to a community effort, including those with ties to Boise State, a new stone now stands beside the tracks on an open stretch of yellow grass dotted with boulders and sagebrush. It’s a quiet place where, on a recent afternoon, the only sounds came from meadowlarks perched on ancient-looking electric wires and the whistle of a passing train. The words on the stone, written in English and Chinese, remember the fallen man, as well as his countrymen for their contributions and “helping to build the West.”

Boise State alumnus Sam Hui (BA, economics, ’90) assisted with wording on the monument and arranged for the translation into Chinese characters. The memorial, Hui believes, is one of fewer than a dozen memorials to Chinese railway workers in the American West and the sole memorial built entirely from private donations.

Honor, respect

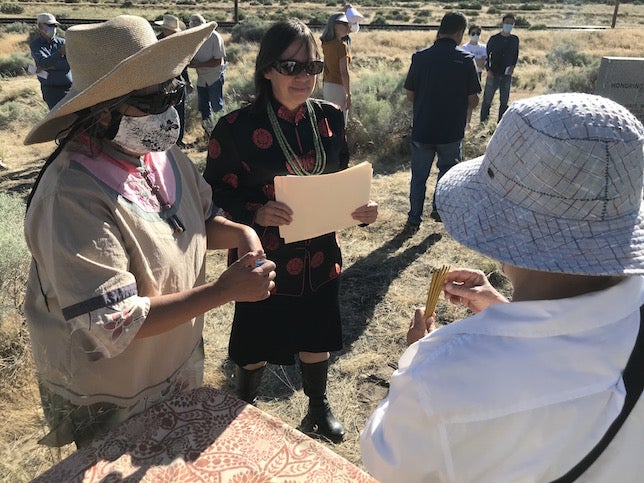

Pei-Lin Yu, an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology and a Fulbright senior research fellow, led a ceremony to dedicate the memorial on June 9. Attended by community members from Boise, from Boise State and Glenn’s Ferry, the ceremony included lighting incense, placing traditional yellow chrysanthemums and pouring Chinese ng ga py liquor near the stone.

MeiChun Lin, a language teacher at Riverstone International School in Boise, read the memorial inscription on the stone aloud in Cantonese, the language that would have been spoken by the Idaho rail workers in the 1880s. Yu read from Maxine Hong Kingston’s book, “China Men,” about Kingston’s grandfather’s experiences as an immigrant rail worker.

“I did not feel worthy to lead the ceremony: my small contribution was to bring people together, remember, show honor and respect,” said Yu. “The program practically wrote itself: all the moving tributes of the participants. The memorial was the work of many hands and many dreams and it was fitting that the ceremony was that way, too.”

Boisean Jim Lance, a retired railroader who started his career with Union Pacific in Pocatello in 1977, learned of the old gravesite around 20 years ago.

“I always paid a little mental respect to this deceased laborer every time I went by,” said Lance.

In 2014, he became operations manager over the area that includes King Hill. Lance led the drive to restore the memorial and build community support for the project. Lance’s childhood friend, Blaine Thomas, who owns Thomas Granite and Marble in Pocatello, donated the memorial stone.

‘Forgotten immigrants’

The bodies of Chinese immigrants who died away from home often were sent back to their families in China. It’s possible then, that the rail worker’s body was never buried in King Hill. That doesn’t diminish the site’s significance for Hui.

Hui’s Idaho roots run deep. His great-grandfather came to Idaho in the 1880s. His grandfather, Don Louie, came to Idaho in the late 1930s. Louie ran the Golden Dragon restaurant where the Grove Hotel now stands in downtown Boise. Hui’s immediate family came to the U.S. from Hong Kong in 1972 when Hui was 6 years old. His family owned the Nam King restaurant at the intersection of State Street and N. Collister Drive in Boise for 38 years.

“The Chinese in Idaho have largely been a forgotten group of immigrants that have been here longer than Idaho has been a state,” Hui said. “Their contributions to the infrastructure, economy and the cultural diversity that they have brought to the great state of Idaho must be told.”

Sites and artifacts

Idaho is home to a thriving modern Chinese community. Boise and Boise State support active cultural groups. Still, the new King Hill memorial stone stands among relatively few tangible remnants of the early Chinese presence in Idaho. This, despite the fact that according to the 1870 U.S. Census, more than a quarter of the residents of the Idaho Territory were Chinese. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred new arrivals from China and prevented Chinese immigrants who were already here from becoming citizens. The law stood for 60 years, which may partly explain why Idaho’s first Chinese residents became what so many call a “forgotten” group.

While the Idaho State Museum collection contains Chinese artifacts – and before its recent redesign displayed a Chinese apothecary and temple altar from Boise – Idaho does not have a museum, akin to the Idaho Black History Museum and the Basque Museum, devoted to Chinese American history. The last of Boise’s Chinatown was lost to urban renewal in the 1970s.

“But if you look carefully, traces of that early presence abide,” said Yu, who is Taiwanese American.

Historic remnants of Idaho’s Chinese history include the name of Boise’s Chinden Boulevard, a portmanteau of “Chinese” and “gardens” that hints at the area’s past, and the former Chinese laundry that houses Bar Gernika in downtown Boise. The U.S. Forest Service maintains the former Pon Yam grocery in Idaho City as well as a Chinese mining exhibition in a historic ranger station in Warren, Idaho. Later this year, an exhibition on Chinese mining in the Boise Basin will open at the Idaho Museum of Mining and Geology in Boise. And the Asian American Comparative Collection at the University of Idaho maintains material cultural items and documents that Yu called “irreplaceable.”

Other remnants include head stones at Boise’s Morris Hill Cemetery and a small structure there for the burning of joss paper, or ancestor money meant to support the departed in the afterlife. Yu had planned to burn paper money at the King Hill dedication, but, fearful of the dry conditions and the danger of fire, burned the bills later that evening for the rail worker and his compatriots.

“I hope they spend it well,” she said.

Listen to a Boise State Public Radio interview with Yu about the project here.

Listen to a Boise State Public Radio interview with Hui about the Chinese presence in Boise here.

– Story by Anna Webb