In 1987, Boise State launched the Master in Raptor Biology program. Today, it is still the only university in the U.S. with a degree of this kind.

Since its start, 122 students have matriculated through the program and changed the landscape of raptor and wildlife biology and conservation as educators, researchers and leaders in institutions and organizations such as the Bureau of Land Management, the United States Geologic Survey, The Peregrine Fund, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and countless universities and colleges across the country.

With over 30 years of active research and numerous published studies on various raptor species, including barn owls, burrowing owls, and his personal favorite, the screech owl, raptor biology professor and former director of the Raptor Research Center Jim Belthoff takes his greatest pride in the successes of his students.

“I think what I get the most satisfaction from is seeing the successes of all of the students that have come through, and all that they’ve been able to achieve. It’s incredible when you put the list together of what our students have been able to do, the fact that many of our students are in high leadership positions for a variety of entities. Boise State, in regards to raptor biology, has a record of achievement that is literally amazing,” he said.

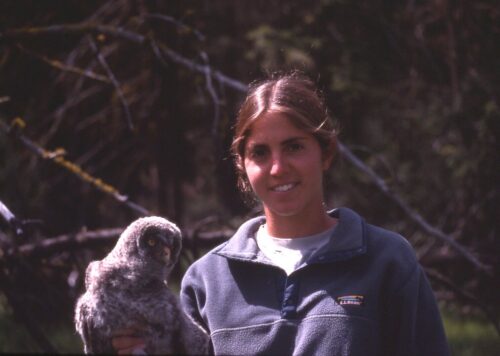

Robin Garwood

Even as a child growing up in the suburbs of Indianapolis, Robin Garwood knew her life would revolve around animals. However, it wasn’t until she was pursuing her Bachelor of Science in Wildlife and Fishery Science at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, in the 1980s that raptors really came into the picture.

Peregrine falcons were still listed as endangered species due to the unintended and disastrous side-effects of the chemical insecticide DDT (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane). As a student, one of Garwood’s field projects in the wildlife management program was as a hack site attendant in the Great Smoky Mountains to help reintroduce peregrine falcons populations into areas where they had been extirpated.

“That really got me interested in raptors,” Garwood said. By a funny twist of fate, as she began looking for masters degrees ‘Out West’, her brother-in-law, a veterinarian living in Boise, asked if she had heard about the new raptor biology program at Boise State.

Garwood applied right away and pursued her masters research by studying wintering bald eagles along the Boise River while taking rigorous classes and investigating the many effects humans have upon the species. She recalled multiple lessons and people that stood out to her during her degree, and mentors that left lasting impressions.

“Karen Steenhoff was my thesis committee chair, a mentor to me, and she was a really strong editor. She edited for professional journals, and taught me a lot about technical writing and thinking, which lasted throughout my career,” Garwood said. “You’re so immersed in the scientific method, and I think that probably is what I took away most: how true, rigorous science really works.”

When asked about the most exciting memory in her work as a wildlife biologist, Garwood calls to mind not just one, but two moments in which she was able to document important ‘firsts’ for endangered species the Sawtooth Mountain Range.

“In 1992, myself and a technician were able to document the first nesting peregrine falcons in the Sawtooth range. So that was really, really exciting time. We found another nest in 1993 and then throughout the 90s we found a few more. That was really gratifying to be able to contribute to monitoring and ultimately recovery of peregrines and taking them off the endangered species list.”

She also documented the first bald eagle nest, her master’s thesis raptor, in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area in 2006.

As a wildlife biologist for the Forest Service, Garwood’s expertise was not limited to raptors, but spanned dozens of other species in the Sawtooth region. In addition to trapping, radio-collaring and documenting species, she also dedicated a substantial portion of her time and energy with the Forest Service to habitat restoration, such as whitebark pine habitats.

Since graduating 35 years ago, Garwood has ‘geeked’ out over the new technologies that improve wildlife biology sciences, but also witnessed many concerning challenges for the future of wildlife.

“There are so many unknowns about what’s going to be faced with climate change,” she said. “Invasive species is a huge one…wildfires…droughts.”

For students about the begin the path to becoming raptor and wildlife biologists, Garwood recommends establishing a few specific traits.

“A couple traits I think that are necessary these days are persistence, curiosity and

optimism, which is very difficult at times. And then also to whatever you’re doing, try to find some joy in it to keep you going, because it can be very discouraging working in this field because of all the challenges that we face.”

Even now as a retiree, Garwood’s own persistence and sense of joy in wildlife shows as she continues to aid in habitat restoration with the Forest Service and breeding bird surveys, in between the many birding trips she has penciled on her calendar.

“Birding – for me – it’s a way to really devote attention when you’re outside, or even if you’re watching from your window. It’s a real way to be in the present and to be focused on what’s going on around you.”

- Written by Brianne Phillips