If you’ve ever lived in a noisy apartment building, you are likely familiar with the way sounds can affect you. Upstairs neighbor starts tap dancing at 6:45 a.m.? Maybe you should go out for breakfast instead of staying in.

Humans are not the only species impacted by sound. As first-year doctoral student Kate Sweet found in her study of 27 song sparrows (Melospiza melodia), high sound levels cause these sparrows to be more vigilant and also to decrease foraging for food.

Song sparrows are common across North America. You’ve likely heard them singing along the Boise Greenbelt. These birds are potential seed dispersers (think of them as tiny, feathered gardeners). They eat insects and serve as prey for other species. But just because these birds are common does not mean that they are not a species to be concerned about.

“Each species plays a role in its ecosystem and is a part of that system’s functioning,” Sweet said. “As species decline or disappear altogether that loss can have reverberating effects on other parts of the system. It’s also important to note that many bird species, even those that are not currently listed as threatened or endangered, have been experiencing population declines in the recent half-century across North America.”

Sweet is a first-year student in the Human-Environment Systems program at Boise State and works alongside with Assistant Professor Matt Williamson. As a master’s student, Sweet completed this research with Associate Professor Jesse Barber in the Barber Sensory Ecology Lab.

“Kate is a phenomenal ecologist,” Barber said. “She is as comfortable troubleshooting code for statistical analyses as she is getting up before dawn to film songbirds!”

Students in this lab study species such as bats, moths, spiders and birds to answer a critical question in current conservation research: How do animals process sensory input? Ideally, the answers to this question will provide knowledge that will shape conservation policy and best serve the diverse species that inhabit an ecosystem.

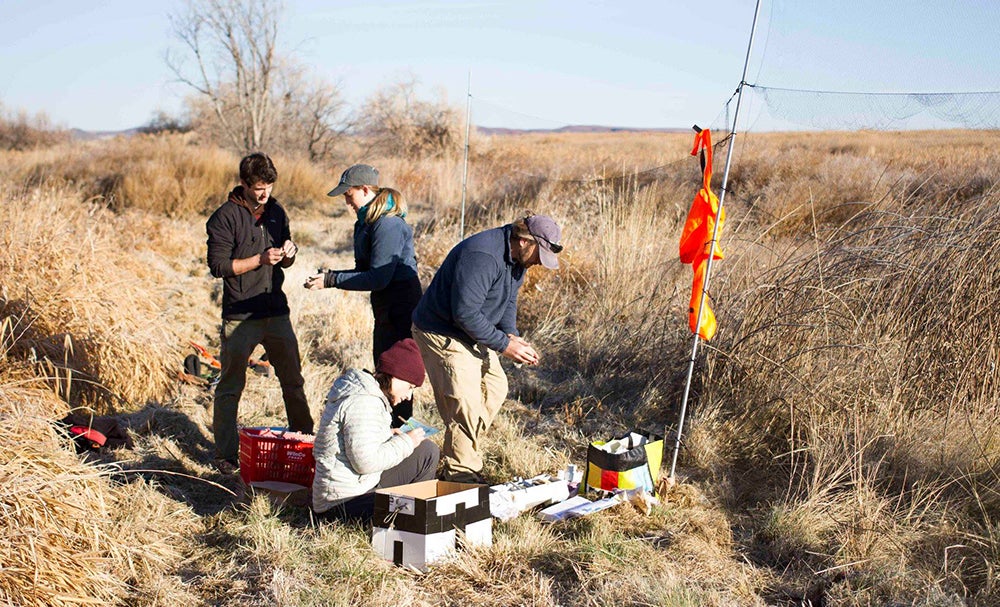

To get a better understanding of how high levels of sounds were impacting song sparrows, Sweet and her colleagues first captured 27 sparrows in mist nets at a wildlife management area. The team released the sparrows in a foam-lined lab room at Boise State with a large seed foraging section. From an adjacent room, the team played different anthropogenic and natural sounds–such as car traffic noises and the rush of white-water, respectively–and videotaped their foraging behaviors for analysis.

The team found that loud noise can negatively impact foraging behaviors in a common bird species. Sweet says this research adds to the larger conversation about how we should be paying attention to noise when we think about conserving wildlife and natural spaces, as well as in our own lives.

“While completing my master’s degree I became really interested in the policy and decision-making side of conservation, and how that process ultimately shapes outcomes for species,” Sweet said. “The issue of species conservation in the face of biodiversity loss is often a socio-political problem as much, if not more than, a biological one. In my doctoral degree I hope to investigate the human side of wildlife conservation.”