Ana Maria Dimand, Boise State University and Benjamin M. Brunjes, University of Washington

*This article is reprinted from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site that features research and opinion pieces authored by expert faculty from around the world – including experts at Boise State, like the piece below. Please note: opinion pieces authored by Boise State faculty do not necessarily reflect the views of the institution.

As the U.S. recovers from the pandemic, the Biden administration is working to rebuild relationships across levels of government, from the top to the bottom, that were strained during the presidency of Donald Trump.

In November 2020, Biden offered urban leaders a seat at the table in coronavirus recovery efforts, promising to avoid partisanship. Addressing the National League of Cities in March 2021, Harris praised urban leadership on COVID-19 – cities like Seattle and New York were among the first to respond to the pandemic, developing testing protocols, tracking new infections and supplying equipment for hospitals – and highlighted the administration’s plans to help pay for improvements to local infrastructure.

The COVID-19 crisis highlighted the importance of government leaders working together.

The U.S. government system, called federalism, shares power among the national, state and local governments. This system allows local control over most day-to-day government decisions. Local control means that policies can be tailored to the needs and limitations of each community.

But with the onset of COVID-19 in early 2020, tensions in this shared system boiled over. Instead of collaborating, the federal government rebuffed state and local governments desperate for critical information and lifesaving supplies.

States and cities competed over medical equipment, testing capacity and supplies and other needs. Densely populated cities, many feuding with the federal government, were hardest hit.

Federalism seemed to fail, slowing the response and leading to deaths.

Change in approach

In contrast to the previous administration, the Biden administration is treating local governments as key partners in a variety of areas, including public health.

It has taken steps to give local policymakers more control over the allocation and distribution of COVID-19 vaccinations, while setting national policies to hasten the availability of vaccines.

Reasserting closer relationships between the federal government and state and local partners may signal a shift toward more collaboration in general.

The federal government can use its power and position to drive change at the local level. A more collaborative relationship can help the federal government understand communities’ needs, leading to new policies and priorities. Close partnership may also increase awareness of federal resources that are available, helping state and local governments identify programs to better support their residents.

But as our research shows, federal dominance can also be counterproductive.

How federalism does – and doesn’t – work

Federal and state governments are responsible for national or regional priorities, such as defense, diplomacy and the raising and redistribution of tax revenues.

But local governments deliver the most-used public services, including schools, transportation, parks and public health. As a result, local governments are perhaps the most important in people’s daily lives.

Local governments both make and implement policy. In areas where the federal and state governments are silent or inactive, local governments often innovate to address community needs. That freedom to innovate helps local governments generate policies that can work their way up and across the federal system.

For example, despite backlash from state and national leaders, various cities – like Austin, Los Angeles, Virginia Beach and Washington, D.C. – have led the way on social and environmental policies, adopting and advocating for higher minimum wages, fracking limitations, sanctuaries for Second Amendment rights and reducing law enforcement violence.

Scholars have noted changes in the dynamics of these relationships throughout history. During some eras, the federal government has more power over policymaking. At other times, state and local governments exert greater influence.

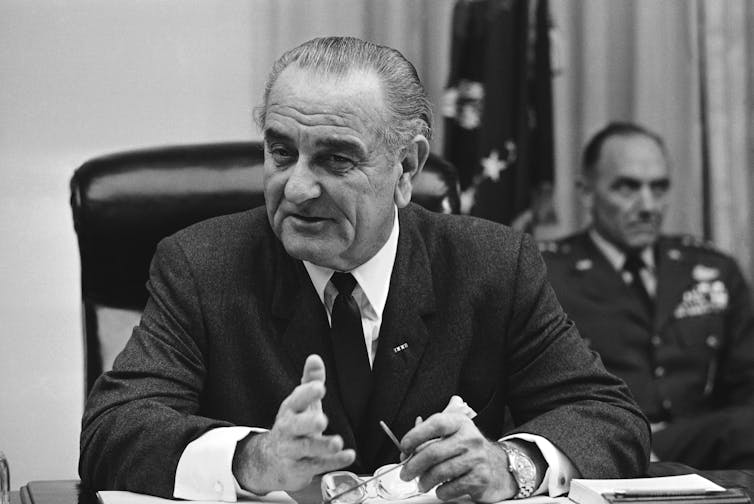

For example, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society welfare programs – Medicare, Medicaid and food stamps – increased the federal government’s influence on state and local governments. New federal requirements mandated spending on social programs, often requiring matching funds from state and local governments. And new state and local agencies had to be established to implement federal priorities.

Federal dollars shared with local governments to fight poverty came with strings attached. Examples include requirements to meet environmental standards and adopt nondiscrimination policies.

With the advent of welfare reform in the mid-1990s, the federal government relaxed some of these requirements. As a result, state and local governments were given more flexibility over policy and spending decisions.

Our recent research indicates the balance of power in the federal system affects government performance and the safety of Americans. During the COVID-19 response, the federal government failed to partner with state and local governments. As a result, there were problems finding and delivering crucial supplies like masks and ventilators, leading to needless deaths.

Historically, presidents have taken a range of approaches to managing the federal system.

Johnson’s Great Society programs expanded the authority of the federal government. Federal agencies gained the power to create and manage the details of the effort to eradicate poverty, hunger and discrimination.

President Richard Nixon’s “new federalism” sent money in so-called “block grants” to state and local governments to carry out different federal initiatives. This allowed local governments some power over policy design and implementation.

President Ronald Reagan’s “pragmatic federalism” emphasized privatization – using private-sector organizations to deliver services – and decentralization. Reagan used markets to deliver government services through competitive contracts and grants.

In more recent years, scholars have accused Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama of returning to the more coercive federalism of Johnson’s Great Society. To encourage state and local governments to adopt federal priorities, federal funds under these presidents again included strings, increasing tensions between these levels of government.

[Understand what’s going on in Washington. Sign up for The Conversation’s Politics Weekly.]

Under President Trump, these tensions reached an apex. Cities clashed with the federal government over immigration policy, law enforcement violence and health care – and, ultimately, over how to handle the pandemic.

Biden’s approach

Much of Biden’s proposed sweeping infrastructure plan addresses problems of rural and urban areas, such as caregiving, clean energy and health care. Other parts confront regional issues, such as transportation, where states play an important role.

With the understanding that coordination among all levels of government helps address problems more effectively, one step Biden might take is to revive the U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. This commission operated from 1959 to 1996, offering presidents and federal agencies guidance on issues that spanned the federal system’s layers. The commission helped address abuses of power in the federal system and strengthened partnerships between governments.

As scholars, we know that policy issues are rarely independent. Global climate change affects local transportation policies, while health care issues are often closely linked to education and agriculture.

Local governments are important players in the federal system. Over the next year, they will be critical in continued efforts to vaccinate the American public and prepare for disasters like hurricanes and wildfires.

Given the complexity of modern policy problems, renewed consideration of how all levels of government can approach such big issues could help solve them.

Ana Maria Dimand, Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Administration, Boise State University and Benjamin M. Brunjes, Assistant Professor of Public Policy, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.