Once upon a time, towns like Robinette, Oregon, dotted the American West. Robinette had a train depot, a hotel, and a tavern shaped like a military quonset hut. Residents tended orchards where trees hung heavy with peaches, apricots and walnuts. Robinette’s schoolhouse may have been the most important building in town. Old black and white photos show Christmas pageants there. They capture dances and holiday meals where guests wore overalls and sat at long tables covered by checkered tablecloths.

In 1957, the people of Robinette left their homes to make way for the construction of Idaho Power’s Brownlee Dam. Today, the lost town of Robinette sits under 100 feet of water at the bottom of the Brownlee Reservoir.

Oregon native Bob Reinhardt, an assistant professor of history, estimates that dozens of towns experienced similar fates to Robinette, flooded by hydroelectric and irrigation dam projects from the 1920s to the 1970s.

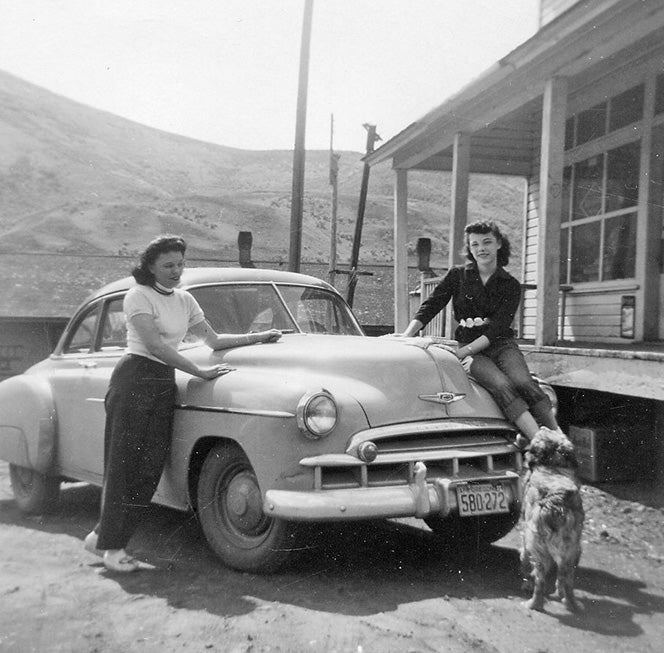

Photos courtesy of the Baker County Library District

www.bakerlib.org

Reinhardt has embarked on a multimedia public history project, “The Atlas of Drowned Towns,” that will, for the first time, document these once vibrant places. Reinhardt received a $30,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. He’s assembled an interdisciplinary team of scholars with expertise in the humanities, natural sciences and technology. The team will collect oral histories from the public – the people who lived in towns like Robinette. The project will include underwater archaeology at former townsites and will incorporate digital imaging from 3-D capture of personal artifacts, to virtual and augmented reality experiences.

“All communities are unique, just like all people are unique. I think it’s fascinating, and distressing in many ways, that such places were so quickly and easily erased — or so it seems, although I hope to show differently,” Reinhardt said.

Read more: Professor aims to catalog ‘drowned towns’ of the American West