Universities often play a vital role in helping students develop their professional identities, and understand the values and skills needed to perform highly in their field. As Boise State University continues to grow and serve students from varied backgrounds, it is increasingly important that our graduates have confidence in what they do, and learn to trust their work and own abilities to succeed. Megan Frary, associate professor in the Micron School of Materials Science Engineering (MSMSE), is part of an interdisciplinary team taking a hands-on approach to helping students do just that.

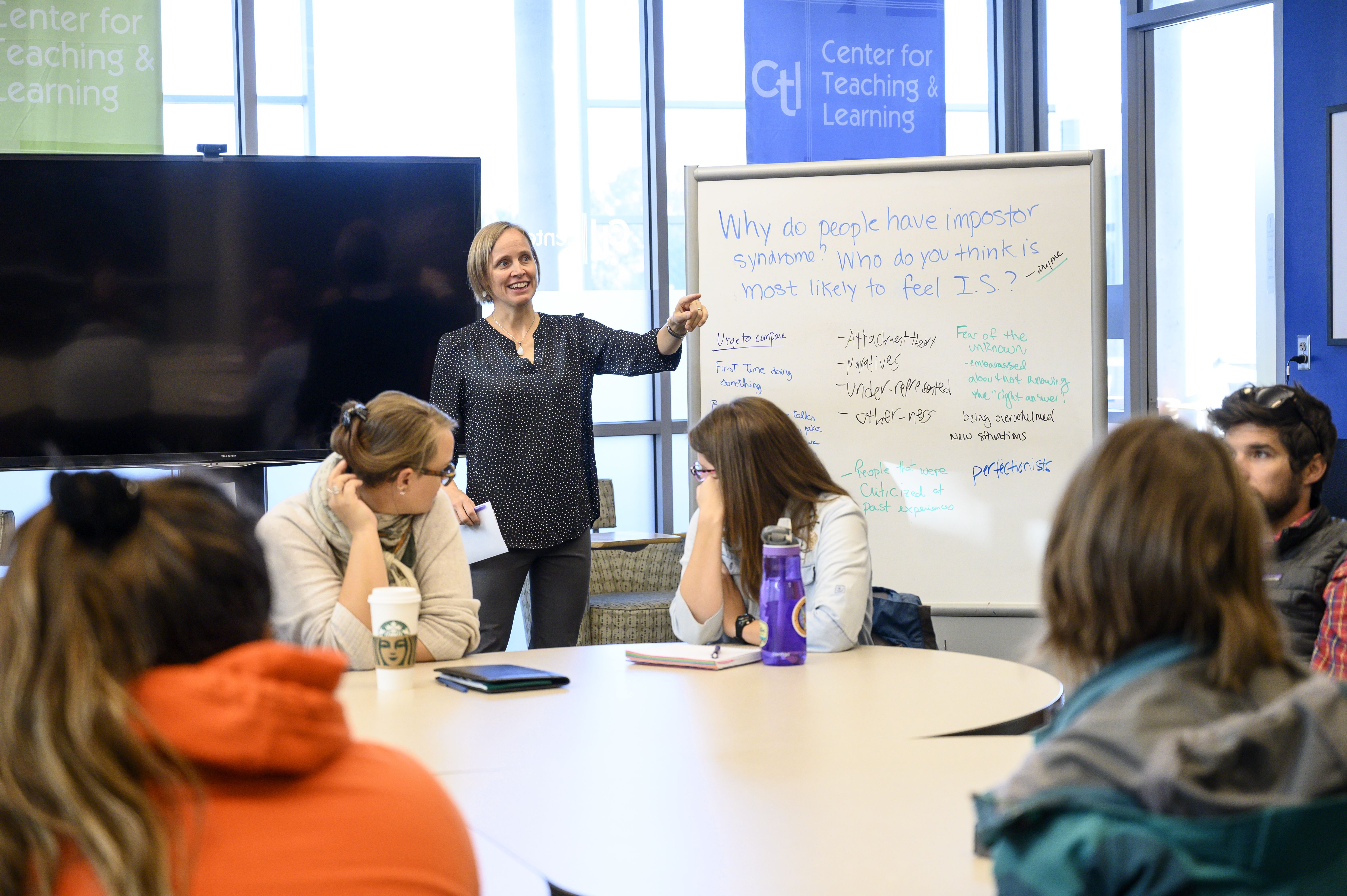

In addition to her work for MSMSE, Megan Frary is the coordinator for graduate TA support in the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL), where she works to support graduate students instructors in developing more effective teaching techniques in higher education. From her own experience earning her master’s and doctorate degrees in materials science and engineering, Frary already knew that lecture-heavy teaching methods didn’t serve engineering students well. Frary came to Boise State to teach in 2005 and started attending courses and workshops for faculty at the CTL to look for alternative methods in engineering education.

“Four or five years in, I started to be more interested in the impact I could have by working with people on their teaching rather than through the materials research work I’d been doing,” said Frary. “I looked at Susan Shadle [executive director of the CTL] and thought, ‘She’s got a PhD in inorganic chemistry. She made that transition, that means I could, too.’”

In 2012, Frary was invited to help coordinate the Graduate Certificate in College Teaching program. This certificate includes classes on course development, teaching and assessment methods, and also allows students to co-teach or independently teach their own classes. The program launched in 2013, and graduate students from 18 programs across six colleges have completed the certificate. Frary says, “I love how interdisciplinary it is. One student was doing his masters of fine arts in poetry, and here I was with my engineering lens, and we worked really, really well together. I love seeing that play out time and time again.”

Her work with the CTL has also led to interdisciplinary research opportunities. In 2016, Julianne Wenner, an assistant professor in College of Education, and Paul Simmonds, an associate professor in the department of physics, ran the pilot iteration of a project exploring the impact of teaching one’s discipline to others on the teacher’s professional identity development. Frary joined the team in 2017, teaching participants instruction techniques in one of her graduate college teaching courses.

As part of this project, students in taking graduate-level STEM courses develop a lesson to teach a scientific topic to pre-service elementary teachers who are enrolled in ED-CIFS 333, Elementary Science Methods. The pre-service teachers use what they’ve learned to develop a lesson for elementary school children. Here, graduate students are serving as subject matter experts for other educators, who in turn deliver their work to actual students.

In 2018, the National Science Foundation granted funding for this work, now called GIFT (Graduate Identity Formation through Teaching) and now includes Wenner, Simmonds, and Frary. Donna Lewellyn, the executive director for Boise State’s Institute for Inclusive and Transformative Scholarship, joined the team in 2018.

When asked about the term ‘professional identity’, Frary describes it as a sense of belonging in one’s discipline: “Do they see themselves as competent? Do they feel like an expert, do they feel like they belong?” In some cases, students do not feel competent, they do not feel like an expert, they may believe they do not belong where they are. Hancock and Walsh (2014) assert that a strong sense of professional identity contributes to career success and fulfillment, whether graduates choose a career in academia or industry.

Frary says that students often go into the experience feeling underqualified and overwhelmed. “A lot of times, the graduate students say, ‘I’m not an expert, I don’t know enough to teach it.’ By the end, however, they realize, ‘Oh, I am an expert, I am qualified. I know what I’m doing, and I have useful knowledge I can share with others.’ By virtue of talking to people who are not [in your field], you can show why what you do matters.”

Not all students in the GIFT program intend to go on to be teachers after they graduate. Learning to share complex information with an outside audience helps scientists, engineers, artists, language interpreters, and other specialists excel as part of multidisciplinary teams. Multidisciplinary teams that communicate well benefit from diverse perspectives on problem solving and varied skill sets that can result in higher performance.

“Knowing how to give a presentation is one thing, but it does not really teach you how to have a conversation.” Says one former GIFT participant. “The back and forth of [teaching] … [is] making your mind more agile by doing backflips on the spot, [and] coming up with questions.”

For more information, visit the GIFT project homepage. The graduate certificate program has paused admissions for fall 2021 while the team re-evaluates their own delivery methods and adjusts for new teaching demands post-COVID-19.