The idea of an underwater town carries an undeniable dark romance. Take St. Thomas, Nevada. In the 1930s, residents moved out to make way for the construction of the Boulder Dam. The dam, renamed Hoover in honor of President Herbert Hoover, raised the level of Lake Mead and 60 feet of water swept over St. Thomas. Today, when there’s a drought, you can see the crumbling remnants of the town’s hotel, its ice cream shop, and other structures.

But most often, said Bob Reinhardt, an assistant professor and director of the Working History Center in Boise State’s Department of History, towns flooded by hydroelectric and irrigation projects in the 20th century were first razed. Crews burned buildings and uprooted orchards. In some cases, whole towns were relocated. In 1925, the Bureau of Reclamation moved the town of American Falls, Idaho, across the Snake River to make way for the American Falls Dam. The first American Falls, settled in 1800, sits at the bottom of a reservoir.

Despite the number of towns lost to federal western water projects – Reinhardt estimates there have been dozens – scholarship has been sparse.

“We know more about this in China and some African countries. There’s a term, ‘development-induced displacement,’ a jargony term that means people who were moved because of big economic development projects, especially hydroelectric projects. When it comes to the American West and the United States more broadly, a lot of these places are passing out of memory and into myth,” he said.

The Charles Redd Center for Western Studies recently awarded Reinhardt a John Topham and Susan Redd Butler Off-Campus Faculty Research Award to support research for a public digital history project, “The Atlas of Drowned Towns.”

Reinhardt wants to recover the lost histories of the towns and communities inundated by hydroelectric and irrigation dams over a 50-year period, from the 1920s to the 1970s.

His research will begin with the Snake River and its dams. He plans to meet with agencies and local historical societies, determining what kinds of materials already exist, including archives, maps, yearbooks and more. The other part of his research will involve creating new resources through oral history interviews and “history harvests” – public events where people share stories and artifacts. Reinhardt is working on an application to the National Endowment for the Humanities to support that part of the research. Reinhardt wants to involve fellow historians in the project, as well as social scientists and experts in the technical and computer fields who can capture 3D images of artifacts.

While his will be a historic study, the phenomenon of flooded towns is relevant today.

“We’re not moving in direction of displacing fewer people. Climate change may bring about even more,” said Reinhardt. “In the U.S., we don’t have thoughtful policies that appreciate communities’ sense of place. One of the things I find so interesting is a paradox. The American West is a culmination of placemaking, but also of placelessness, of moving on to the next thing when necessity dictates it.”

New ways to look at history

Reinhardt’s research is historic in nature, but it will include new and even surprising aspects. His project will incorporate student (undergrad and graduate) research, with an aim towards pointing those students to meaningful careers in history. The project is interdisciplinary. Reinhardt is speaking with the Department of Kinesiology about enlisting SCUBA divers to help with underwater archaeology at former townsites. The project will incorporate the latest technology in digital imaging: from 3-D capture of personal artifacts to virtual and augmented reality experiences.

The project will also rely on community engagement. Reinhardt will host “History Harvest” events during which residents can bring their historical items to donate to a local archive or have them scanned or 3D imaged for the project. A website portal will let residents upload photographs, scans, or interviews. Reinhardt envisions smartphone apps where users could mark GPS points relevant to inundated communities.

“The project will grow organically to include other river systems throughout the West and beyond,” said Reinhardt. “Most history projects are relatively fixed and permanent: a book is published, and the topic is done except for maybe additional epigraphs or editions. But this one is built to evolve and grow over time as more people — scholars and community members — get involved.”

Q&A: more about the project

(Interview edited for length and clarity.)

Q. How did the topic of drowned towns first captivate you?

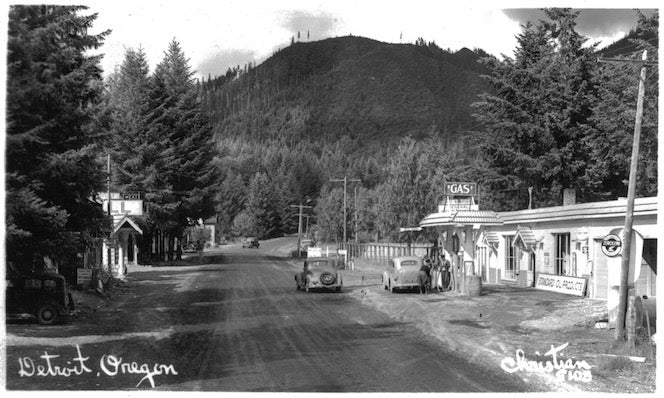

Reinhardt: It started when I was working on my master’s project at the University of Oregon, a history of the North Santiam Canyon (culminating in the book, Struggle on the North Santiam: Power and Community on the Margins of the American West). I got intrigued by the story of the town of Detroit, moved to higher ground in the 1950s for the construction of the Detroit Dam and the creation of Detroit Lake.

Q. How many towns and villages in the West were flooded for federal projects?

Reinhardt: If we have a dozen dams on the Snake River, we can say that half of them displaced communities of some size. If you extrapolate and look at the Columbia River, you’re looking at maybe another 10. So I say ‘dozens.’ For a historian, that’s uncomfortably vague language. But this grant will allow me, starting with the Snake, to look at each dam, see how much property the federal government acquired, and see if those properties contained town plats.

Each one of the dams displaced somebody, even if it was just a few peach orchards. When a family or a community plants fruit trees, that’s a sign that they planned to say for a long time. Some of the sadder things in the historic record is when people talk about their orchards being ripped out. (Trees and structures, if left in place, could later cause problems when they washed downriver, so they were removed.)

Q. At the height of dam building, was there any public outcry? It’s unimaginable that there wouldn’t be today.

Reinhardt: Generally speaking not, though there are records of citizens voicing objections – a woman named Ma Dickey in Detroit, for example. She ran a hotel. The Army Corps of Engineers said they would pay her to move to Bend. She didn’t want to leave and start over. But most of the outcry came from relatively marginalized voices calling for environmental preservation, but not from the communities themselves.

Within the communities, what you see is a spectrum – from acceptance to full-throated support for economic development and the prosperity it brings. Most of this dam building was happening within the Cold War’s context of consensus. You don’t go against feds when we need to unite against the communists. Hydroelectric projects supported the aluminum industry, which supported the aeronautic industry. No one wanted to stand in the way of that.

In the communities, people in support of the projects would say that their towns were dingy and that the chance to move offered better things – more homeownership, better landscapes. One of the things I hope the project does is tune into the ways people lamented the loss of their homes in ways that coexisted with that sensibility.

In some cases, they hung onto artifacts, sometimes entire buildings. One of the stores in Robinette, Oregon, flooded by the construction of the Brownlee Dam in 1958, was moved and still stands in Richland, Oregon. Detroit’s Cedars Lounge and Tavern was saved and moved to higher ground.

Q. Did this kind of flooding take place in other parts of the country?

Reinhardt: It was predominantly in the West because we have so many river systems. You do see some in the Eastern U.S., and there is scholarship, and a few stories here and there, in Pennsylvania and other places. But when it comes to large projects that require enormous federal investment, most happened in the West during what we call the “go go years,” after World War II and into the ’50s and ’60s.

Q. When did it end?

Reinhardt: By the 1970s there’s quite a bit of push back, mostly from environmental groups that had become more powerful and politically savvy. And the feds, the Carter administration, were saying they didn’t want to spend money on these projects anymore. That being said, they did build the Lower Granite Dam (Washington State) in 1975.

Q. Are there any other lost towns we know about in Idaho besides the first American Falls?

Reinhardt: Lake Cascade drains into the Snake River. Someone told me there used to be a town nearby. That’s the sort of story I want to explore with this grant. Once I start looking, I know people will start telling me stories.

Resource Links

- Listen to Reinhardt’s interview with Boise State Public Radio about the project.

- Visit a website devoted to the project.

- Find more information about the Redd Center and its awards.

– Story by Anna Webb