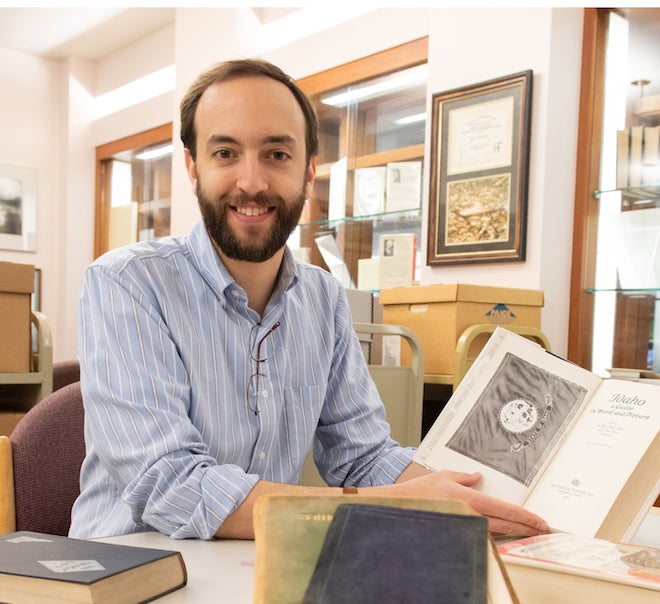

Alessandro Meregaglia, an assistant professor and archivist/librarian at Albertsons Library, has embodied his role as an archivist by uncovering a lost piece of Idaho history.

Meregaglia was researching the history of Caxton Printers, the century-old, family-owned publisher in Caldwell, Idaho, when he discovered the unpublished manuscript of the “Boise Guide” written by Idaho novelist Vardis Fisher in 1938. Before Meregaglia found the guide, it sat, forgotten in a box in the Library of Congress, for 80 years.

Meregaglia described the guide as “an unfiltered look at Boise of the mid-1930s, the city in the years after the Great Depression.”

Rediscovered Books, the independent Boise bookstore, is publishing the manuscript for the first time in a book titled “Vardis Fisher’s Boise.” Meregaglia edited the text with Boise freelance editor Laura Wally Johnston. He wrote a new introduction for the 200-page book and added around 100 historic photographs. The book features a cover design by artist Ward Hooper, a Boise State alumnus.

Fisher’s guide teems with the facts he thought visitors should know. Idaho’s liquor laws didn’t allow establishments “catering to night-life” to serve alcohol, for example. Those establishments let patrons rent lockers to store their own liquor that bartenders would serve to them. Taxi fare within city limits was 25 cents for up to four passengers. Julia Davis Park boasted “excellent” clay tennis courts. The guide includes a tour from Boise to Table Rock via what was known as the “Skyline Drive.” The road, warned Fisher, was safe for experienced drivers, but not those unaccustomed to “moderately difficult mountain roads.” Some of the language Fisher used to describe Boise’s ethnic groups is offensive by modern standards. It’s of its time and preserved in the guide for historic accuracy.

Publishing the book is a thrill, said Bruce DeLaney of Rediscovered Books.

“We decided years ago that whenever we had the opportunity to bring local history to light, we would. Fisher was someone who was looking at Boise nearly 100 years ago. There are things in the book people will recognize, and things they won’t,” he said, noting Fisher’s unique voice and sensibilities.

Fisher’s acerbic style was one of the reasons the guide sat unpublished for so long.

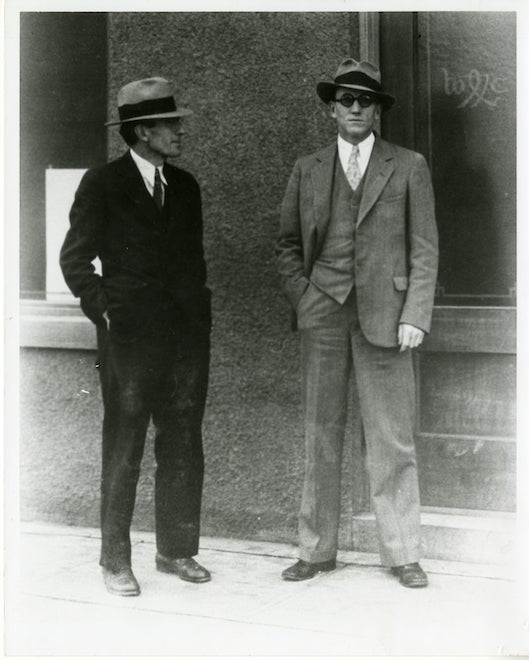

‘Bad boy of the Project’

Fisher, who died in 1968, wrote some 30 novels, as well as poetry and essays. He was born and raised in Eastern Idaho and spent the last three decades of his life in Hagerman. During the Great Depression, Fisher was part of the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal program that hired out-of-work writers, researchers, historians and others who produced thousands of publications, including oral histories, children’s books, and guide books for states and cities. Fisher worked for the Federal Writers’ Project from 1935-1939. During that time he was the principal author of three books on Idaho, including the critically-acclaimed “Idaho: A Guide in Word and Picture” in 1937.

“Idaho” was the first guide book published for any state, thanks to Fisher’s close relationship with James H. Gipson, owner of Caxton Printers, who accelerated its publication. This caused a bit of a scandal, said Meregaglia. Government officials had wanted the Washington D.C. guide to be published first. Henry Alsberg, director of the Writers’ Project, first bogged Fisher down with 2,000 revisions, then, when that didn’t work, Alsberg sent an assistant to Idaho to get Caxton to stop the presses. Fisher and Gipson plied the assistant with cocktails instead, and sent him back to Washington, said Meregaglia. The presses kept rolling, and Alsberg gave Fisher a nickname: “bad boy of the Project.”

This may have been prophetic.

A ‘provincial and reactionary town’

Following “Idaho: A Guide in Word and Picture,” Fisher wrote the “Boise Guide.” The Federal Writers’ Project required writers to find local sponsors in order to publish their work. Fisher shopped his guide around. The Boise City Council, the Idaho State Library and the Idaho State Historical Society all passed, said Meregaglia. They found Fisher’s writing and his appraisals of the capital city too opinionated.

To be sure, Fisher wrote tenderly of the city at times: “At night, searchlights make sorcerous loveliness of the gardens” (to describe Platt Gardens at the Boise Depot). But just as often, he called out the city’s shortcomings.

“Upon any of several streets can be found enough incongruous architectural ineptness to abash any lover of the beautiful,” he wrote. Without Boise’s many trees, he added, “the city would not inappropriately invite the metaphor of a peacock divested of its feathers.”

Frustrated with the guide’s cool reception, Fisher wrote to Alsberg. “I have no assurance yet we can get sponsorship for the ‘Boise Guide’ in this provincial and reactionary town.”

In time, Fisher departed from the Writers’ Project to pursue fiction. He left the manuscript behind.

Meregaglia’s discovery of the lost text came about as he researched Caxton, poring through books and papers. He kept noting references to the “Boise Guide.”

“A footnote in a book led me to an oral history with Fisher where he talked about the guide. That led me to the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.,” said Meregaglia. He traveled there in summer 2018.

“I had a good idea of what box it would be in. I requested that box, and there it was,” said Meregaglia. “To finally see the manuscript and know that it was real and complete — it was a moment of great delight.”

Book Release Party

Rediscovered Books will host a release party for “Vardis Fisher’s Boise” at 7 p.m. on Jan. 30 at the store (180 N. 8th St). Meregaglia will be part of panel of experts who will put the “Boise Guide” in historical context.

– Story by Anna Webb

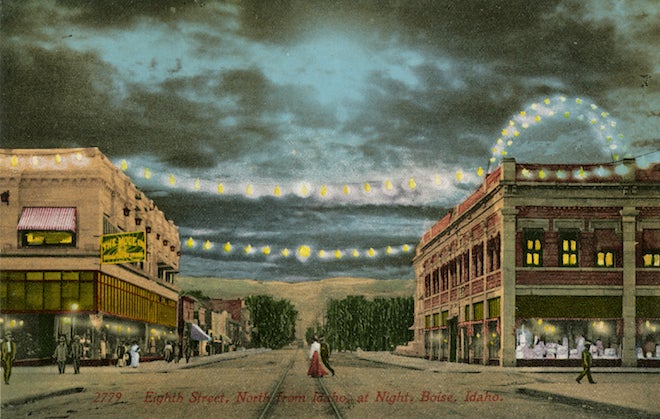

New Point of View

Diego Casillas, a senior from Jerome, Idaho, put his graphic design major to use this year as a student employee in Boise State’s Visual Services department. The department captures images of campus life – from athletics to academics – and shoots photos for use in Focus. In his position, Casillas has created several stunning visual projects, including these photos that blend together images of Boise, new and old to illustrate Meregaglia’s unique and historic find.

“I overlaid the photos, skewed them till they matched as best as they could, added the brushing effect through a drawing tablet and decided the overall layout of the project,” Casillas explained.

Working in a creative department for the university “has allowed me to juggle different types of projects and challenges me creatively,” he added. “It lets me know in what ways I thrive and what ways don’t work well for me.”