Restoring the Boise Foothills One Plant at a Time

By Cienna Madrid

In June 2016, an errant, illegal firework sparked a blaze that consumed more than 2,500 acres of grassy, sagebrush-filled foothills surrounding Boise’s iconic Table Rock – the mountainous plateau jutting out of the foothills northeast of the city. The fire devastated established wildlife habitat and shut down miles of popular hiking trails originating from the Old Idaho Penitentiary and traversing up to Table Rock itself.

But once the embers cooled, landowners – including the City of Boise, Idaho Department of Lands, Idaho Fish and Game, and private citizens – faced another battle, this one against time, erosion and a host of invasive species that were ready to outcompete slower-growing native plants like sagebrush for the area’s sparse resources.

That’s where Boise State alumna Martha Brabec stepped in. After receiving her master’s in biology in 2014, the City of Boise hired Brabec in 2016 as its first ecologist to maintain and preserve the 13 open space reserves – totaling more than 5,000 acres of land – owned by the city.

The Table Rock fire offered Brabec an opportunity to apply the scientific principles she learned in graduate school under Matthew Germino, U.S. Geological Survey scientist and Boise State adjunct professor, to land management on a larger scale. Funded by a generous $100,000 donation from Friends of Zoo Boise, Brabec led a collaborative effort to quell erosion and the propagation of invasives like cheatgrass and medusahead rye.

Service Learning

In 2018, Brabec teamed up with Boise State’s Service-Learning Program to include students enrolled in an environmental studies class in planting sagebrush within the Table Rock burn perimeter.

“The class was integral to the success of the ongoing restoration project at Table Rock,” Brabec said. “I could count on these students to do the heavy duty work – carrying buckets up steep areas and planting sagebrush and perennial bunch grasses. When you have a certain number of plants that you need to get in the ground, student and volunteer support is critical for restoration success.”

“This service-learning project has been so successful because Martha creates a learning environment for students,” said Mike Stefanic, a service learning coordinator at Boise State. “She’s really a co-educator, which is unique. She knows the content of what students are learning, she’s able to talk about current research and how the city is responding.”

Senior Haley Lister, a native of Urbana, Illinois, who will graduate in May with a degree in biology, has been able to put her degree in practice as an intern for the city. There she works as a liaison between Brabec’s rehabilitation efforts and student volunteers, among other things.

Lister says her education at Boise State gave her the scientific knowledge of how and why to employ adaptive land management strategies, “but I had a hard time explaining why all that mattered to people who were not equally in the loop. Martha has given me so many opportunities to practice being a bridge between scientists and the public as well as understand how research is applied through management,” she said.

Through students’ field work, they saw firsthand how quickly weeds flourish in fire-ravaged areas, and native plants like sagebrush – which grow slowly but can live up to 100 years – struggle as cheatgrass quickly grows and propagates, depleting soil nutrients even as it alters them.

“Martha stating how long this project would take before we saw improvement was the most eye-opening part,” said Alyna Wheeler, a senior from Denton, Texas, studying environmental biology. “It was a harsh reminder that our natural environment and ecosystem is very fragile, and the impacts that we have on it not only cost tons of money to help restore or manage, but could potentially be irreversible.”

New Strategies

This kind of on-the-ground education has been formative not only for students, but for the rehabilitation effort as a whole. Exactly where students planted new sagebrush starters is key because while re-seeding native plants in newly burned areas is nothing new, Brabec’s approach to rehabilitation is fueled by experiment and design.

“We’re employing adaptive management techniques and using what we learn to implement more effective restoration efforts in the future,” she said. “This is a unique opportunity for a land manager.”

Large-scale sagebrush restoration efforts in the Great Basin desert, in which Boise resides, have been largely unsuccessful in the past. This is because while big sagebrush grows from Arizona to British Columbia, it has adapted to be highly site specific.

“If a sagebrush is growing on a north facing slope at 4,500 feet, it is adapted to live there, under those specific climate conditions,” Brabec said. “So when reseeding or replanting sagebrush landscapes with a wide range of elevations, aspects, and topography, is important to match the climate of sagebrush seed origin to the climate of the planting site. If you apply the same seed source across a highly variable landscape, it is unlikely that sagebrush will establish in areas where the climate conditions are much different than where the seed source evolved to grow.”

In the current climate of megafires, which can span more than 100,000 acres, reseeding sagebrush on such a large yet nuanced scale presents an obstacle for land managers.

“Essentially, we’re taking seedlings and replanting them in the harshest environment possible, and we need genetics on our side,” Brabec said.

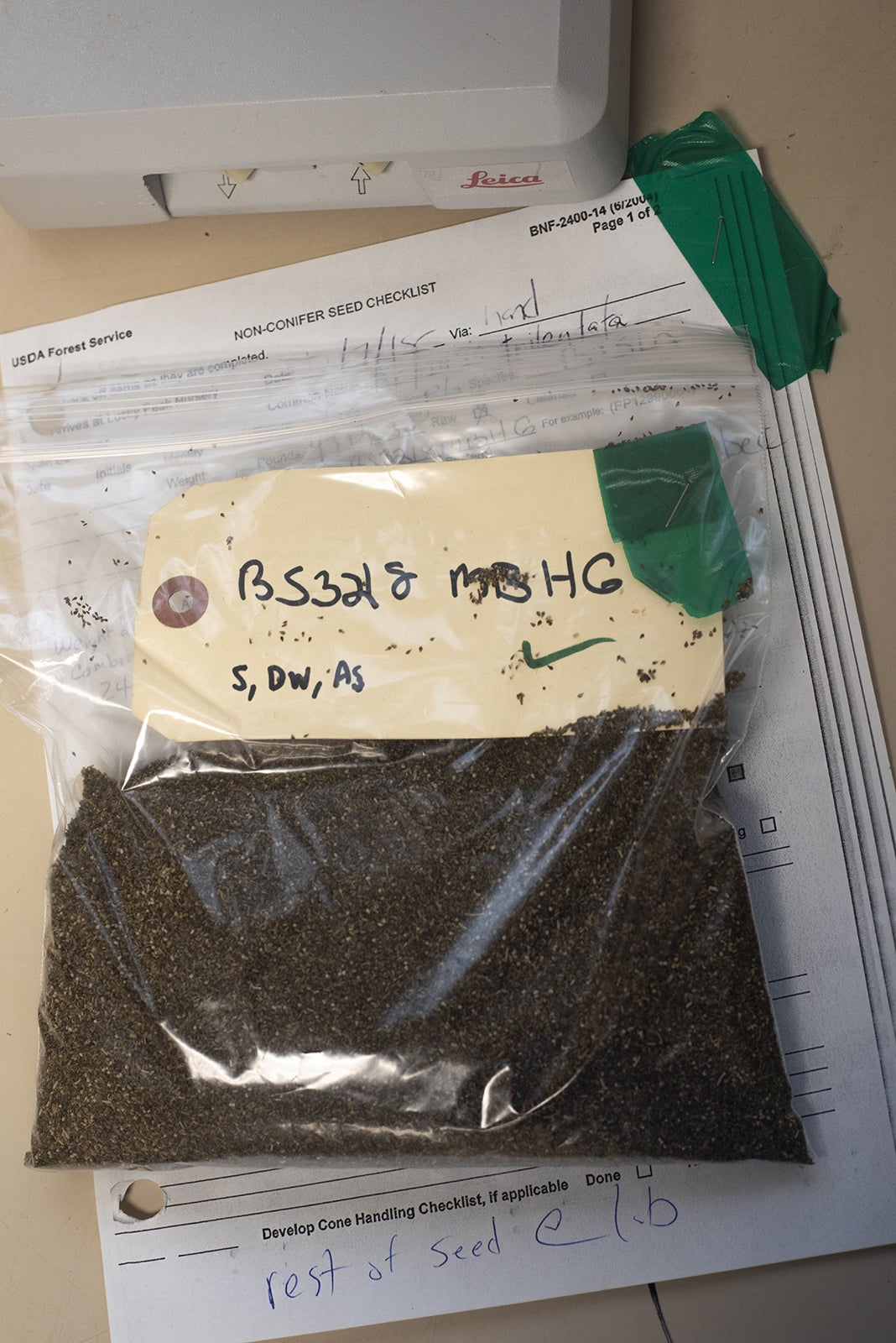

Brabec and roughly 30 Boise State students have spent the past several seasons painstakingly collecting sagebrush seeds at different elevations and topographic positions on the landscape. The group collected more than 50 pounds of sagebrush. Each pound of sagebrush contains approximately 2.5 million seeds.

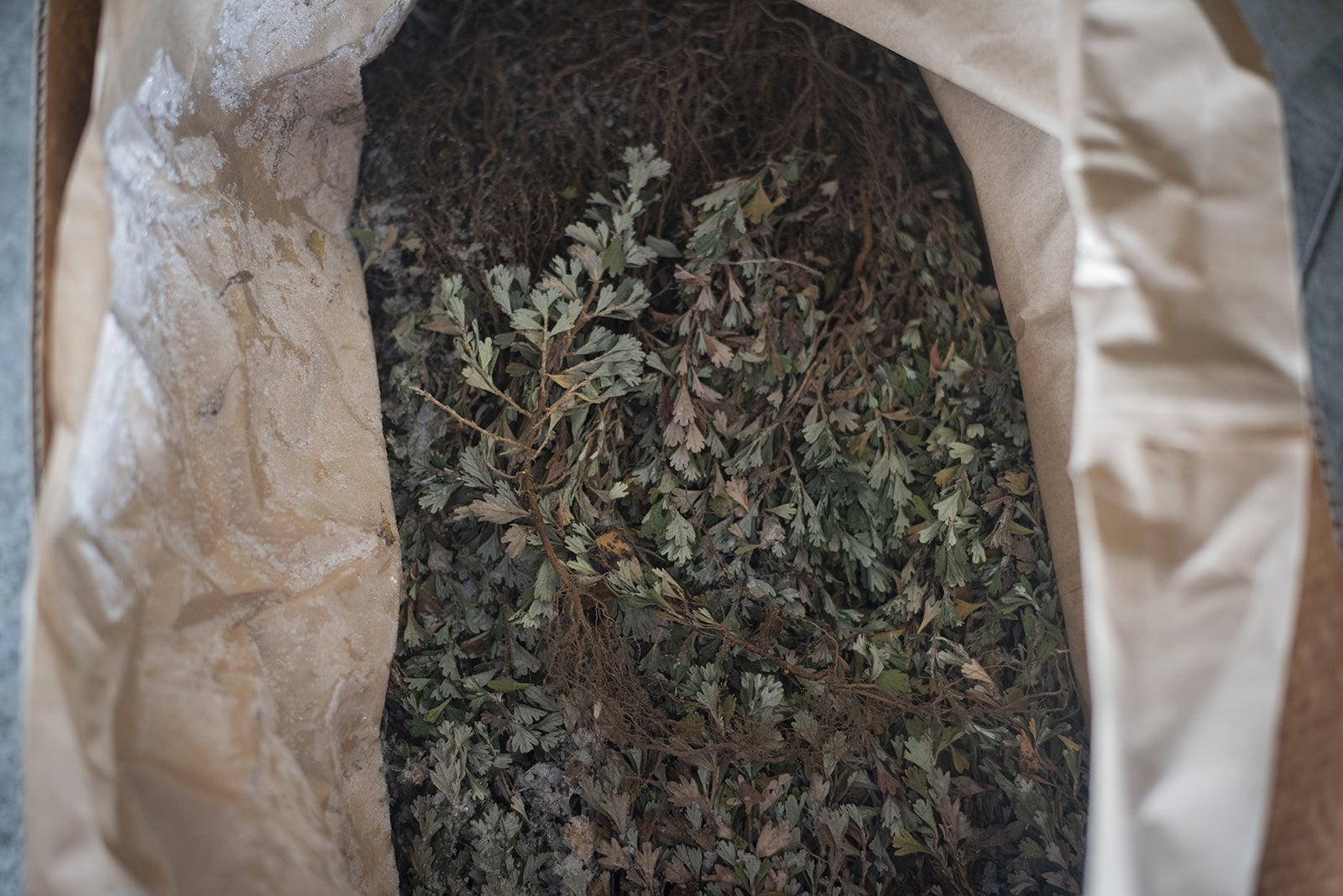

These seeds then were taken to Lucky Peak Nursery, where they were sorted, cleaned and a selection was sprouted for planting in new site-specific areas. To date, volunteers have planted more than 18,000 sagebrush and bitterbrush seedlings, as well as native grasses and pollinator-friendly wildflowers, in the Table Rock burn area.

Weed Warriors

In spring 2019, a new crop of Boise State students and community volunteers began helping Brabec with another aspect of restoration: identifying and pulling invasive weeds as part of her Weed Warrior program, which is run through the city. In the two-part program, volunteers learn to identify invasive species versus native species. Brabec then organizes two-hour field trips where students and volunteers look for native plants and pull weeds in areas where management is needed.

(left) Volunteers ready to replant Tablerock | photo by Allison Corona

“The golden hue you see in summer on the foothills is typically just monocultures of invasive species,” Brabec explained. “We have a wide variety of noxious and invasive weeds – cheatgrass, medusahead, scotch thistle, Canada and musk thistles. We can control some weed populations by hand pulling, especially if the weed populations are small or isolated. We can also protect some of our rare, endemic, plants like Aase’s onion, Boise sand verbena, and Andrus biscuitroot by weeding. I just need the labor to help me do it.”

Lister said that thanks to the Weed Warrior program, every time she hikes she now fills her pack with weeds and trash, and takes satisfaction in the work.

“This isn’t some garden here for just my pleasure, it isn’t a chore – we are weeding vast landscapes that exist nowhere else on Earth. We are weeding not just to increase our quality of life, but the quality of life for all organisms that we share this space with,” Lister said. “You see your impact, and you take pride in those positive changes.”

Crystal McBrayer, Boise State’s Creative Services Director and a local artist whose work addresses invasive species and uses dyes from native plants, enrolled in Brabec’s Weed Warrior program last summer and has been active in seed collection and invasive weed harvesting since that time – as have her two young daughters.

“My artwork talks about my connection to the land and how important it is to me, so as a parent it’s my responsibility to teach that, as we’re caretakers to our environment,” McBrayer said.

Rehab work extends far beyond the gradual restoration of Table Rock into the city’s 12 other foothills sites. As more and more people use the foothills, threats to the environment from trail erosion and the spread of invasive weeds have grown. Brabec’s Weed Warriors have removed Russian olive trees in the Hulls Gulch Reserve, Bethine Church River Trail and Hyatt Hidden Lakes Reserve. Early settlers brought the invasive trees to Boise in the 1800s because of their drought resistance. Research suggests that Russian olives use up to 75 gallons of water a day, while native cottonwood and willow trees typically consume half that amount. Over the next few seasons, the Weed Warriors will revisit these riparian areas and plant native trees.

Continuing Restoration

Brabec’s goal is to get people to participate in a full cycle of restoration – from harvesting seeds to growing them, then planting those seeds to create a sense of communal investment in the foothills that hug the city.

“It seems that there has been a paradigm shift in land management – there’s no such thing as a ‘one and done’ treatment anymore,” Brabec said. “You can’t just treat an area and walk away, you have to have the capacity and ability to come back year after year and do rehab and management. The great part is, the public can be part of that.”