The city of Boise, notable for its ongoing growth spurt, bills itself as a green and sporty city – a place where one can bike the Greenbelt to work, roam the nearby foothills, even float the Boise River through the heart of downtown. This characterization, one that has landed Boise on a slew of “best of” lists, overlooks the fact that Boise once was a far more industrial place. It was home to steel plants, foundries, slaughterhouses, warehouses and a blue-collar workforce that kept them all running.

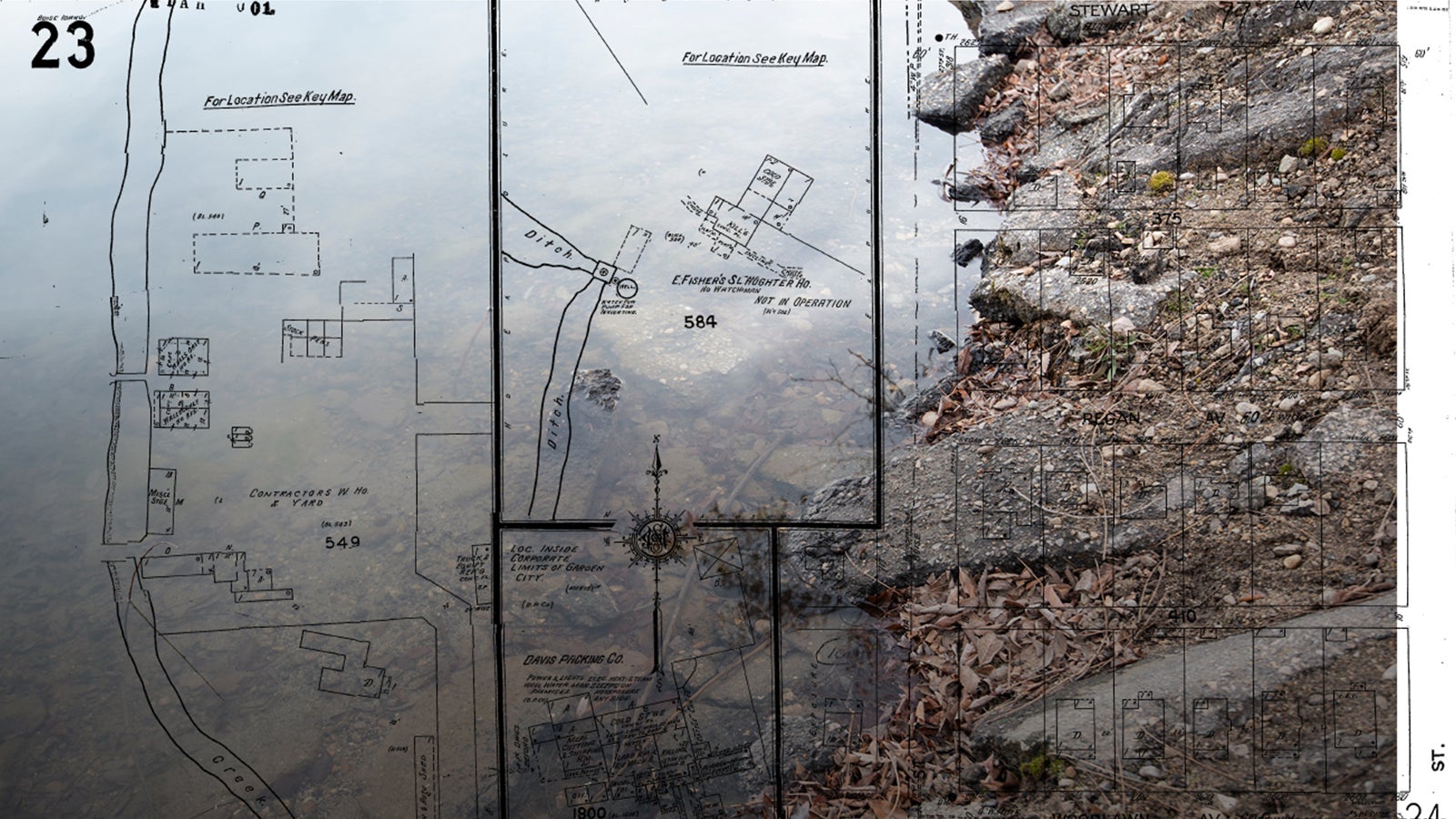

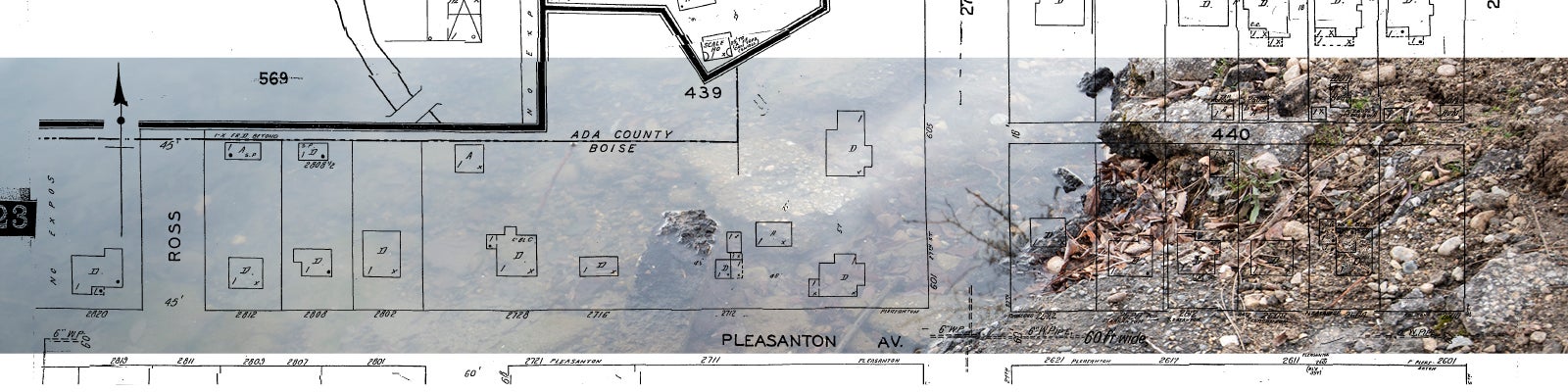

Jennifer Stevens, an environmental urban historian and assistant clinical professor in the School of Public Service, is researching this largely forgotten part of Boise’s history. She will explore the “deindustrialization” that transformed Boise into the aspirational green city it is today, and examine how racist or classist forces may have contributed to it.

“My hope is that this research will resonate with people who have been displaced, pushed out because of gentrification. My goal is that even if we can’t bring people back, we can bring their stories back, give them a sense of place in Boise’s history that’s been totally obliterated,” Stevens said.

A New Look at Old Ground

Studying Boise’s changing character through the lens of deindustrialization is a largely untapped area of research. While Idaho has a number of remaining historic sites associated with industry, from the still operating Amalgamated Sugar factory in Nampa (built in 1942) to massive, abandoned mining compounds across the state, many remnants of Boise industry are long gone, said Dan Everhart, outreach historian at Idaho’s State Historic Preservation Office.

Exceptions include Quinn’s Pond and Esther Simplot Park – former gravel extraction sites – and the sandstone quarries near Table Rock. Other sites, like the brick yard in Hulls Gulch in the Boise Foothills, have left no trace.

“One of the quirks of Boise manufacturing and production might be that it differs from what you would expect because of what Boise is like today,” said Everhart.

For example, a Boise businessman named H.H. Bryant, opened a Ford Model T assembly line in 1914 near Front Street. Bryant was married to the sister of auto magnate Henry Ford.

Still, said Everhart, “No one thinks of Boise as a place where autos were produced. Ever.”

Stories for Newcomers and Old Timers Alike

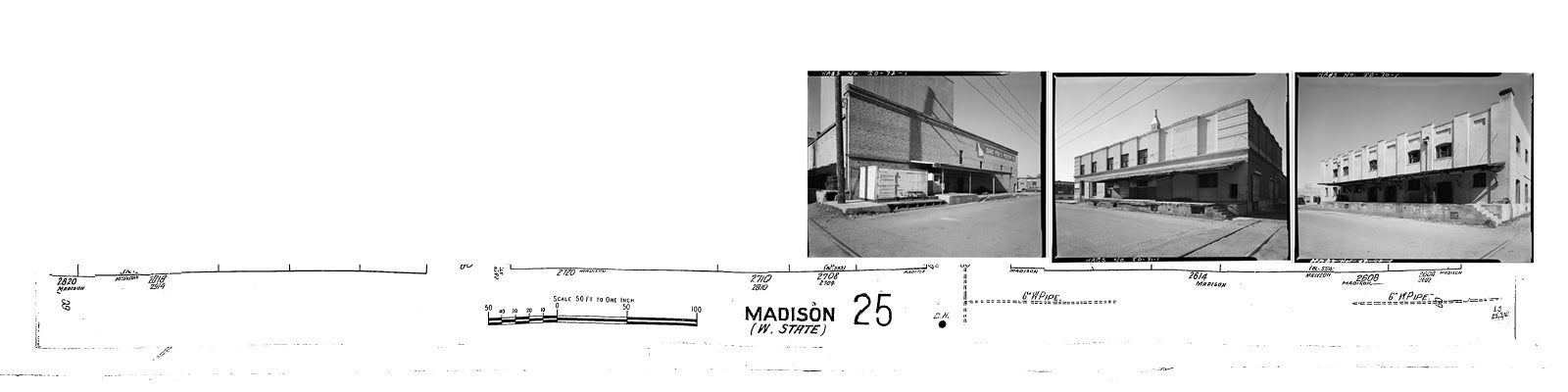

A $30,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) will pay for planning and research. Stevens then will seek additional support to translate her research into a form the public can use. Possibilities include an interactive website or interpretive signs placed at former industrial sites across the city – like Gate City Steel that operated on the east end of Warm Springs Avenue for close to three decades until the early 1970s, or the Baxter Foundry that cranked out metal parts just below the Boise Depot (the family built the Baxter Apartments that still stand on north Second Street). A walking tour is another possibility, said Stevens – one that could include the former warehouse district near Eighth Street/BODO, for example, once home to a taxidermist, industrial laundromat, cold storage and now home to upscale apartments, restaurants and retail.

David Pettyjohn, executive director of the Idaho Humanities Council, noted that the grant Stevens received is highly competitive. One of the challenges in the humanities, he said, is finding ways to share historic information with the public beyond traditional forms like books and lectures. He praised the public outreach aspect of Stevens’ research and its mission to help the city better understand its own roots.

In addition to her work with Boise State, Stevens, who grew up in Boise, founded Stevens Historical Research Associates, a historical consulting firm. She also serves on the city’s Planning and Zoning Commission. She got the idea for her research into Boise’s deindustrialization at a planning and zoning meeting when Boise developer Bill Clark mentioned that his proposed housing development would sit on the old steel factory site on Warm Springs Avenue. At that time, Stevens hadn’t known that Gate City Steel existed. She got intrigued, and started uncovering other lost sites.

She hopes her current project will engage both longtime residents and newcomers.

“So many people are drawn here by the desire to create a new identity. I want them to understand the richness and depth of people who were here before,” said Stevens.

A New Field School at Boise State

Stevens is teaching Boise State’s first urban field school in the spring of 2019. Her students are steeped in Boise’s deindustrialization story. Their research will inform any website, walking tour, or place markers that come from Stevens’ grant.

The field school, Stevens said, “is structured as a humanities lab complete with research teams. It gives the students in our interdisciplinary urban studies program the opportunity to conduct undergraduate research to see the value of the humanities in the context of current urban policy issues.”

The students are working in three teams, studying Eighth Street, the former rail yards where JUMP is today, and Esther Simplot Park. The latter was once home to a slaughterhouse, a cement plant and an airstrip – a sharp contrast to the manicured lawns, walking paths and water features there today. Students say that field school has changed their perceptions of Boise, that they can’t drive by old buildings without wondering about their original uses. They’re seeing ghosts of the city that once was, “especially as Boise grows and tries to create its identity,” said Savannah Willits, a senior majoring in urban studies and community development.

“It’s important to realize where that identity is coming from, and whether it’s authentic.”