While other parts of the country are characterized by the people who live there — the stolid Midwest, the hospitable South, the sophisticated Northeast — “When people talk about the West they generally remark about everything but the people,” said Lily Lee, an assistant professor of sculpture in the Department of Art. They focus instead on the landscape, one that is by turns imposing, peaceful and foreboding, what Lee calls a “last place,” a rare frontier.

“I truly love these things about the West, but I want to acknowledge the people here, our traits, habits, culture, views and attributes.” — Lily Lee

Born and raised in Pullman, Washington, Lee said she is “constantly questioning the identity of the American West” in her work. This has led to the transformation of modest materials into evocative sculptural pieces. It has created her intense connection to community — both on campus and beyond.

After observing that westerners have a unique pride in their ability to pack and haul heavy loads in their trucks, Lee created “Nets and Flaps” in 2016, a series of sculptural works based on hauling and pickup accessories.

(right) Concealment, handwoven, hand-dyed nylon, auto body parts, 2016

Photos courtesy of artist

She elevated the accessories into ritual objects. She hand-wove mud flaps. She strung glass seed beads into cargo nets. The pieces hark back to a shared heritage of covered wagon travel and the embrace of labor and self-sufficiency that lives on, even as the region urbanizes.

“I think of the bright, exuberant colors and the large scale of these pieces as celebratory,” said Lee.

Her creation of handwoven tarps for “Nets and Flaps” and its intense physicality helped inspire her current, and considerably darker body of work, “The Great Basin Murders.”

Weaving Shrouds for the Forgotten

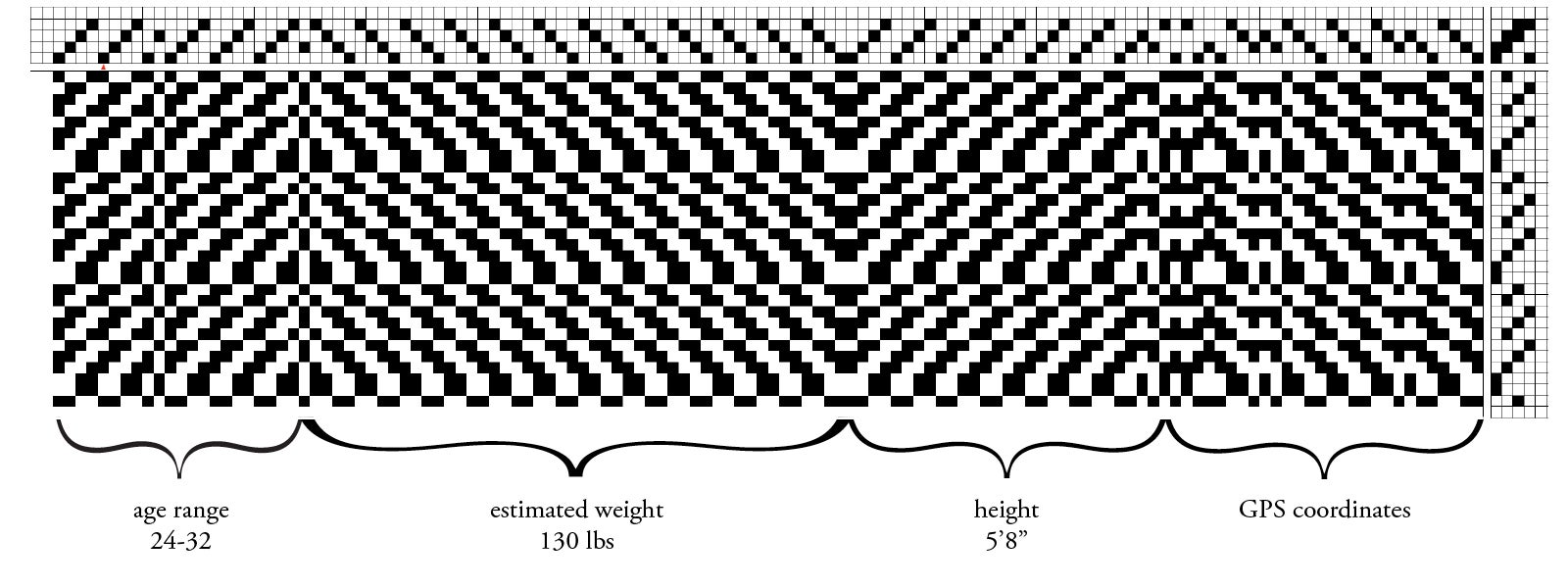

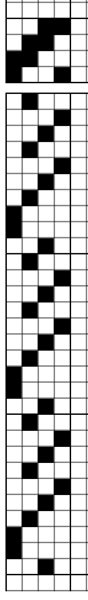

In this series, Lee weaves burial shrouds that memorialize unidentified female victims of murders that took place across the West for decades until the mid-1990s. Lee researches victims through the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs, and The Doe Network: International Center for Unidentified and Missing Persons. She collects data — victims’ height, weight, age, the GPS coordinates of the sites where their bodies were found — and uses a weaving software program, Fiberworks, to translate the numbers into original patterns. Lee weaves a shroud specific to each woman on her four-shaft 45” LeClerc Nilus jack style floor loom. The shrouds match the height of the women they memorialize. The density of the weave patterns, or “ends per inch,” reflects the state of decomposition of their bodies.

“I am interested in these cases of unidentified human remains because they possess this duplicity of being cold and impersonal — the technical, legal format of the databases and objectification of a human as forensic evidence — yet there are these very intimate and humanizing components like photos and descriptions of clothing and jewelry that give the individual an identity, even if their actual, legal identity remains elusive,” said Lee.

She finds ways to integrate those humanizing details into her work. “The Shroud of Bitter Creek Betty,” a woman so named because a trucker found her body near an Interstate 80 turnout in Wyoming called Bitter Creek, features an embroidered rose based on Betty’s tattoo. “The Shroud of Shafter Jane Doe,” whose body was found near the Interstate 80 off-ramp to Shafter, Nevada, includes pink threads because this unknown woman was wearing pink nail polish when she died. A hunter found Devil’s Gate Jane Doe in the Devil’s Gate area east of Elko, Nevada, in 1972. Lee searched local thrift stores to find a blue acrylic sweater that might be similar to the one found near Jane’s body. She wove its fibers into Jane’s shroud.

The Shroud of Bitter Creek Betty

Lee considers the media she uses, “how I manipulate them, what their presence means and their expected purposes especially outside of art making,” she said. In keeping with her interest in material that is not elegant — she frequently uses industrial materials and synthetics like nylon and polyester — she weaves the shrouds using rejected cotton tea bag string that she gets for free from the Bigelow Tea plant that’s been in operation in Boise since 1983. In some cases, Lee dyes the string with tea to approximate victims’ skin tones.

Some shrouds are plain because of the absence of detail in law enforcement files. “I embrace that,” said Lee.

Even the simplest of her shrouds is labor intensive, charged with the purpose of “being a protective covering that the victim didn’t get.” Each takes on a devotional quality and an undeniable poignance. The websites Lee uses for research list more than 12,000 instances of unidentified remains — some unidentified, no doubt, because no one missed these marginalized residents of the American West.

“I see the particular locations where these victims were found as beautiful, but desolate and forlorn sites along highways outside of cities including Elko, Nevada, Rock Springs, Wyoming, and Sheridan and Ucon, Idaho, to name a few. To me they feel like the end of the earth metaphorically, or the most removed place from society the perpetrator could find,” said Lee.

Keeping Cases in the Public Eye

Lee recently completed her fifth shroud, devoted to a woman known as Thousand Springs Jane Doe whom tourists found in Nevada in 1974, her body and clothing burned. But Lee’s work doesn’t end when she weaves her last stitch. She researches the cases that inspire her artwork in an attempt to cross reference missing persons reports with unidentified victims. In 2017, she became the Idaho and Oregon director for The Doe Network, a nonprofit group of volunteers that collects tips from the public, sheds light on cold cases and provides information for law enforcement.

Lee met Jerry Johnson, a detective in the Idaho County Sheriff’s Office in Grangeville, a couple years ago. She called him to ask about an unidentified skeleton dubbed “Mr. Bones,” found in Idaho County in 1984. She’d thought she’d found some clues — they ultimately didn’t match up — about the skeleton’s identity.

“Half the battle with these cases is keeping the spotlight on them,” said Johnson. “The media is interested for a while, but that fades.” Lee’s artistic work puts those cases back in the public eye and improves the odds that they might be solved, he said.

“Lily is an unusual person, so gifted. This is emotionally taxing work, but that doesn’t scare her. She’s willing to dive into these stories. She gets involved with these cases and translates that into her art,” said Johnson. “How could you go to an exhibition of her work and not be moved by it? Especially if you investigate the background behind it.”

And Lee invites viewers to join her in doing that. Her website, lilymartinalee.com, features studio photographs of her shrouds. Each caption includes a link back to victims’ NamUs and Doe files.

Lee serves the community as secretary of the Handweaver’s Guild of Boise Valley, a group of accomplished artisans established in 1972.

She sometimes brings her shrouds to meetings for her fellow weavers to see. They pass them around and study their intricacies in a setting more intimate than a gallery, something like how one might handle an actual shroud.

“People tell me they feel like the victim is here,” said Lee.

The Great Basin Murders

Art professor Lily Lee weaves cold-case data into works of art.