J. Reuben Appelman, a 2005 graduate of Boise State’s MFA Program in Creative Writing, grew up in Southfield, Michigan, a blue collar town near Detroit. This was the 1970s, an era during which a series of unsolved child murders loomed large and ominous over local neighborhoods.

The crimes came to be known as the Oakland County Child Killings. When Appelman was 7 years old, he narrowly escaped being kidnapped. While he ultimately came to believe that the man who tried to grab him on a city street was not the killer, the encounter inspired a long obsession with the murders.

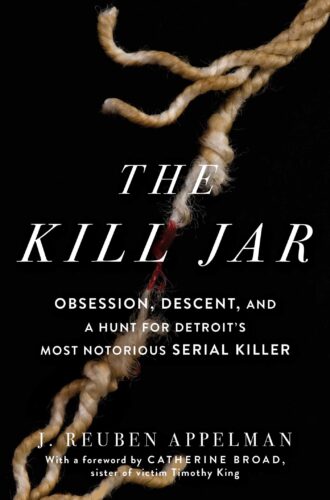

Appelman spent a decade researching the crimes. He requested thousands of pages of documents through the Freedom of Information Act. After investigating buried leads and cover-ups, he reached the conclusion that the murders were not random acts of violence committed by a lone serial killer, but were more likely related to child pornography rings. Appelman’s research grew into his new memoir, “The Kill Jar: Obsession, Descent, and a Hunt for Detroit’s Most Notorious Serial Killer.”

Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon and Schuster, will release the book on Aug. 14. You’ll be able to meet the author. Rediscovered Books, 180 N. 8th St. in Boise, will host a public book release party and reading with Appelman at 7 p.m. that evening.

Appelman told us more about his new book

What’s the meaning of the book’s title?

It’s a metaphor. A kill jar is what an entomologist uses to collect bugs by sweeping them off leaves and into the jar where they die. All four of the children who were murdered were asphyxiated. The killer was roaming the streets, sweeping kids off their footing, the way someone would do to a bug in a garden.

How did these unsolved murders affect the community at the time?

It’s important to recognize that serious crimes don’t end, even with a prosecution. They linger in so many ways. For me, the crimes altered my perception of the world. It became a darker place. No child my age, from the Detroit area, left childhood without having those crimes as part of their interior lives. They affected how people raised their own kids. And as they moved to other communities, the story spread. And I’m here, 30 years later, writing a book about the murders. Evil doesn’t end just because the act is over.

Your own near-kidnapping is part of the narrative in your book. Can you tell us more about what happened?

I was shoplifting in a drug store. An older man saw me. I thought he was an authority figure and that I’d be busted, so I left the store. He followed me out, then followed me in his car for about three blocks. He opened his car door, tried to grab me and I ran.

Although I was interested in discovering whether or not the person who attempted to abduct me was associated with the child killings, once I got deep into the research it became clear to me that he wasn’t, that there were two suspects with very incriminating information pointing in their direction. They looked nothing like the person who made the attempt on me. Those two suspects became the central figures of my investigation, although the book does chronicle more about the attempt on me.

What was the most surprising thing you discovered during your research?

Throughout the decades the official line on these murders was that there was little to no evidence. Years later, I found that not only was there evidence, but there was lots of it — carpet fibers, hair, fingerprints, saliva, semen, blood stains. That means that this evidence was buried, and there was a reason it was buried. That’s the question my book tries to answer.

Do you think the conclusions you reached will result in anyone in law enforcement looking at the murders again?

It’s clear to me that certain individuals, based on today’s prosecutorial standards, should have been indicted and ultimately found guilty of these murders. But at this point, it’s not about looking at the murders again, as much as it’s about acknowledging what’s in the files and widely accepted, within police circles, to be substantive and material.

How did the setting of the story, the Detroit area, add to the narrative?

Detroit is on many levels everything you’ve heard about it, crime saturated, a city experiencing decay. But because of the automobile industry, it’s also been home to some of the most affluent neighborhoods in the country.

A lot of money is being pumped into Detroit, with gentrification of areas that were once thought uninhabitable. Industrial buildings that were for sale for $75,000 seven years ago now have $300,000 condos in them, while a block away people are trading their foodstamps for liquor money. The Detroit I knew still had its seedy underground with steam coming up from the manholes — a metaphor for a lot of insidious doings. At the same time, Detroit is one of the most honest places I’ve ever lived. I think this duality becomes another thread in the narrative.

Your book is the basis for a new docuseries on the Investigation Discovery network. When will we be able to see it?

Shooting will be complete in the near future. I’m the production’s on-camera investigator. The production crew spent a lot of time in Detroit, and their presence drummed up a lot of new interest in the case. Throughout the production, as well as throughout my writing of the book, a lot of people started reaching out, talking about their experiences. Once you enter that world, the flood gates open. I’ve been in contact with victims’ families, and with family members of some law enforcement who worked on the case at the time, with law enforcement itself, with reporters and citizens. The program is four episodes, covers a lot of this material as well as digging extremely deeply into the case, and will air in 2019.

Has writing this book helped you exorcize any darkness from your past?

The biggest thing it’s done is allowed me some breathing room away from the story — my personal story and the story of the crimes. It’s not cathartic. The idea of catharsis seems selfish when there were children who died. But the writing process gave me perspective. It’s allowed me to more forward — not unscathed — but different.

More about Appelman

Appelman lives in Boise. He is a screenwriter and author in multiple genres, and is familiar in Idaho literary circles as a two-time state Literature Fellow. His film work includes the documentaries, “Playground” and “Jens Pulver | Driven,” as well as several produced screenplays. In addition to his literary work and reporting, Appelman works as a private investigator and has shared his expertise in issues of commercial sexual exploitation, child endangerment, law enforcement and more, as a special lecturer in the Honor’s College at Boise State. He is currently reporting on sports, in particular profiles of Ultimate Fighting Championship fighters for bodybuilding.com. He is also working on a fictional crime novel set in Detroit, Mexico and Boise. “Some of our great city will be dealt with in the book,” said Appelman.