By Rebecca Bishop, M.S. student in Boise State’s Raptor Biology program co-advised by Jay Carlisle

They stand upon the landscape – stoic, and seemingly unchanged by time, weather, or season. Hulking mammoths towering, born of equally massive, smooth-barked trunks, and bare, branching, sky-bound tendrils. In these branches you may be lucky enough to see a vulture perched, soaking in the sun’s radiant warmth with wings spread wide, or a pair of lion brothers laid flat, with full bellies heaving, sound asleep in the shade below.

Further glances may reveal the laminated layers of a hive, rich in honey and hidden in the giant’s hollowed out chest.

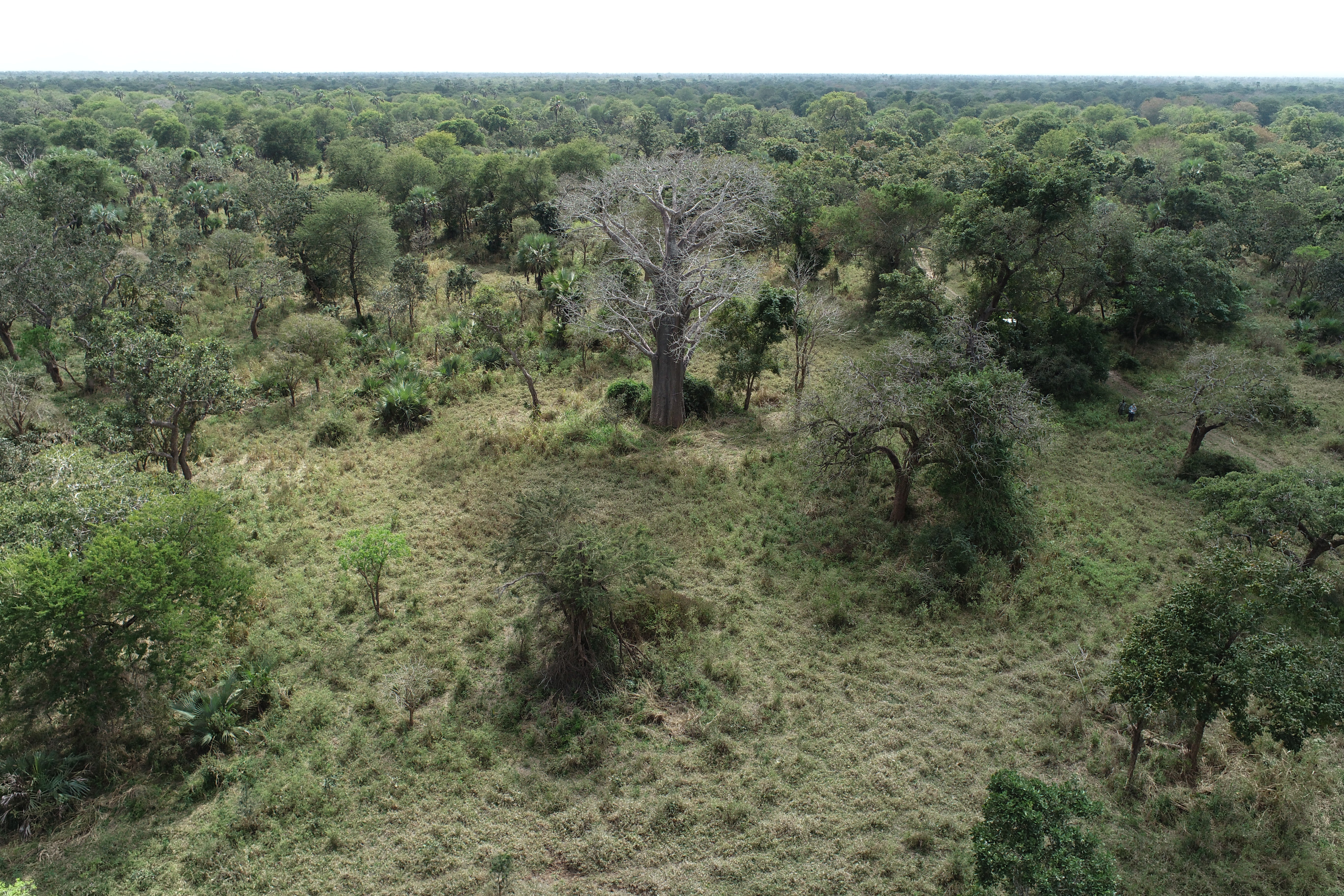

Or perhaps a view of a thorny thicket around its base, teeming with life and community, sounds and greenery. This is the baobab tree (Adansonia digitata), and you will know when you have seen one.

I am not sure what I originally envisioned for my first field season studying endangered African vultures in my pursuit of a Master’s in Raptor Biology at Boise State, but Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique exceeded all expectations. I knew I was in for an adventure, would be pushed in uncomfortable ways, and would finally have an opportunity to see the birds that have fueled me for so long. All of this was true. However, I was completely unprepared for the beauty and power of the place. From its palm veld to its lush floodplain, the wildlife, plants, and scenery did not disappoint. On foot, I traversed prehistoric riverbeds, complete with boulders the size of vehicles, and meandered through grassland seas and acacia forests. As if this were not enough to satiate the spirit, within this setting were these huge, other-worldly trees.

From the moment I laid eyes on one, and before I realized the importance of the baobab, I was unexpectedly transfixed.

I experienced plenty of gleefully giddy moments throughout the season that were completely vulture centric. Barely on the road for ten minutes on my first day in the park, my very first vulture sighting was a soaring White-headed Vulture, the focal species of my graduate work. Weeks later, I remember audibly gasping (and maybe even shedding a tear or two) upon seeing my first vulture chick in a nest. Finally, nothing quite compares to watching over thirty vultures descend on a carcass and pick it clean after just twenty minutes of feeding. But just as was the case with these vulture moments, I never tired of seeing a baobab tree, even if only visible on a distant horizon.

So why does the baobab tree inspire? The most obvious answer is the size. One single baobab tree may be the tallest tree for literal kilometers. I encountered one this season that was over twenty seven meters high and almost just as large around in circumference. Unfortunately, communicating this scale on paper or by photograph is nearly impossible, and it isn’t until you are standing at the base of one, that you can truly appreciate the enormity.

Baobabs also support a multitude of life forms and serve as anchor points within the ecosystem. For example, the tree’s fruit is consumed by a variety of wildlife, while the leaves and bark are utilized by humans for medicinal purposes. African elephants are also known to access the baobab’s impressive water stores during extreme drought conditions.

On top of all these other extraordinary attributes, baobab trees also happen to be a premier nesting spot for vultures!

The White-headed Vulture – a rare, critically endangered species – is a full-time resident of Gorongosa National Park and appears to predominantly nest in the baobab trees at this location. Since our knowledge and understanding of this declining species is considered limited, I aim to fill in some of these gaps by identifying patterns in breeding activity for this population.

From July to October of this year, I had the privilege of hiking to many of these baobab trees to collect data on nest site characteristics, which included tree height, nest height, and habitat type. The nests are highly visible, often from three to four kilometers away, and positioned at the very top of the canopy. To visually access these nests and check for breeding activity, the extreme height required a creative approach. By using a drone, I was able to gain this necessary bird’s eye view. As you can imagine, the view from above was equally as magnificent, further cementing my love for these trees and the spaces they create.

Of the sixty-four historical (and new) vulture nest sites surveyed during this field season, nine were active breeding locations for the White-headed Vulture, and seven of these nine nests were in baobab trees. This is promising news, indeed! In 2022, I will be returning to Gorongosa National Park to collect more nesting data, with efforts focused in the northern part of the park – an area that is a bit of a challenge to access, even during the drier parts of the year. Fingers are crossed for smooth river crossings, more adventure, more vultures, and of course- more baobabs!

This article is part of our 2021 end of the year newsletter! View the full newsletter here, or click “older posts” below to read the next article.

Make sure you don’t miss out on IBO news! Sign up to get our email updates.