After a busy season of curlew and other work, we’ve finally had some time to sit down and write some more stories from the curlew project. This blog post shares the story of two adventures, from the viewpoints of our Research Director, Jay Carlisle, and curlew crew technician, Ben Wright.

By Jay:

We’ve had such enormous success with our Long-billed Curlew satellite telemetry study since 2013 that it’s hard to find reason to complain or wish for more. And, as the curlews we are tracking started leaving breeding areas in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming from the second week of June through early July, the map got more and more exciting and interesting by the day. BUT, during early July, a time when I was just barely catching my breath from an intense 3 months of non-stop fieldwork and travel, I started looking into the details of the satellite transmitter data and soon noticed that two (of a total of 21) transmitters were not moving anymore. Because both of these transmitters were attached in May, it seemed unlikely that the harnesses had fallen off so I became concerned right away.

We’ve previously been able to find five downed transmitters and, in four of the five cases, the news was bad: two had been shot in their breeding area, one had most likely been killed by a raptor soon after arrival in California, and one had died of unknown causes in an agricultural field in California. (The fifth was a happy ending) In all of these cases we were ultimately able to re-deploy the recovered transmitter – and since these transmitters cost over $3,000 each and refurbishing them, if needed, can cost as little as $250, recovering a transmitter can be a real cost savings while allowing us to collect data from another migrating curlew. Thus, it was a no-brainer for me to send Ben Wright, our experienced and all-star curlew nest finder, on a rescue mission or two.

Henrietta’s lost mate

First stop was the Flat Ranch – a Nature Conservancy preserve near Henry’s Lake, to the west of Yellowstone. We had previously tracked a breeding female curlew (“Henrietta”) from Flat Ranch in 2014 and we returned this year to deploy an additional transmitter and study the reproductive success of curlews nesting at the ranch. Erica and Hattie, the two curlew crew field technicians who worked this site this year, had found Henrietta’s nest (with an almost unheard of five eggs!) so we were able to catch her mate and deploy a transmitter on him in late May.

Their nest hatched in June and both parents were seen tending/defending their chicks soon thereafter. Unfortunately, it was his transmitter that showed no movement by early July – and the battery soon died which was going to make the search MUCH harder.

Nonetheless, Stephanie and I created maps showing the latest high-quality locations and sent them to Matthew Ward (great colleague and the Preserve Manager for TNC’s Flat Ranch). He and some high school-aged volunteers spent parts of a couple days traversing the most likely area. When they had no luck, I sent Ben with a rented metal detector to see if he could have any more luck. He thoroughly searched a full 2.5 days, including crawling through a culvert under Highway 20/26 to see if a predator/scavenger might have taken a carcass in there! His search produced not even a curlew feather so we had to be content scratching our heads about this one (& I was wishing I’d discovered the issue sooner!).

We continued to hope the transmitter would turn on again, but had to shift our attention to another transmitter problem and put this one on the back burner.

Heading to Vegas

Meanwhile, a female we had trapped from the nearby Shotgun Valley, just west of Island Park, had begun her migration in late June and her trajectory took her towards the southwest – seeming likely she was heading to where many of our other birds are, either in the Imperial Valley agricultural lands near the Salton Sea or along the northern part of the Gulf of California. I noticed that her last transmission was from a mountain in very southern Nevada and at first I assumed this was an in-flight location while she was migrating past. When the signal didn’t move for a couple days, I got suspicious as the terrain (steep and rocky desert with some vertical cliffs) didn’t look like curlew habitat.

I started contacting local biologists, including Joe Barnes of the Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW) and Melanie Cota of BLM, to see about the land ownership and if a search mission would be feasible. Joe kindly offered to take a quick hike to the spot (~an hour’s steep hike from the nearest road) and came back with news that didn’t surprise me – he saw and heard both juvenile and adult Peregrine Falcons using the cliff areas, adding some circumstantial evidence that a falcon might have been the reason this curlew & transmitter had ended up on a steep mountain. But, he didn’t find any carcasses or transmitters so I still had to decide if it was worth sending one of us on a recovery mission. I couldn’t go because our set up for our annual Lucky Peak songbird migration study was set to start the next day so it’d have to be someone else – and maybe ideally with some climbing experience just in case. As I was weighing up expenses and our chance of finding the transmitter, I gave Ben a choice: more data entry, or a bit of an adventure? It was a no-brainer for him. J

My decision was made easier by the fact that our friend Julie Baughman, who had attended a raptor workshop that Jessica taught last fall, is a pilot for Southwest Airlines and – because she put in some serious hours of volunteering after the workshop – she had been able to donate a couple of passes on Southwest for IBO to use. Thanks Julie & Southwest! Then it was just a matter of hotel, rental car, gas, food, etc. – all costs that would be minor if we could find the transmitter. So I looked at the transmission schedule of the transmitter (picking a couple straight days on which the transmitter would be “talking” during daylight hours), booked Ben a seat on a flight, and sent him to Las Vegas!

By Ben:

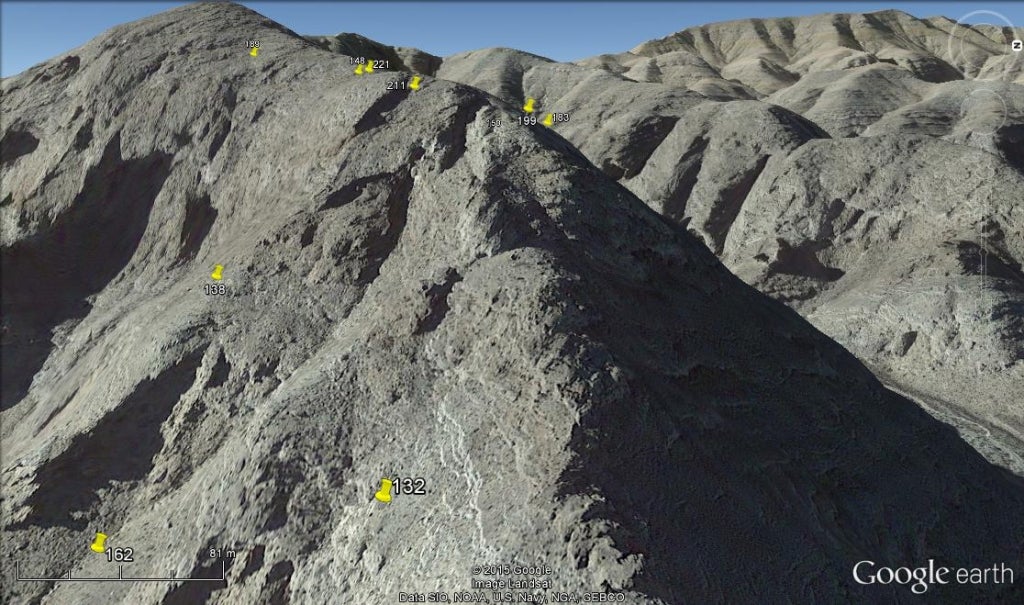

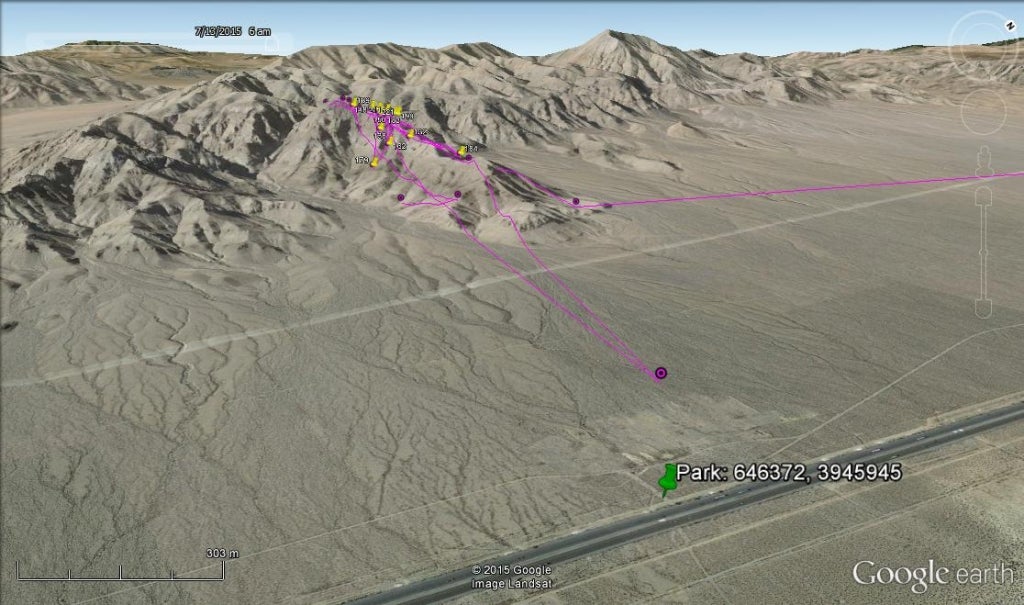

We started the downed transmitter search looking at a map Stephanie had created. Her map had the most accurate locations that the transmitter had sent out. There was a cluster of six points near the top of a ridge. We decided that at the cluster would be the best place to first search for a signal coming from the transmitter.

In the afternoon on July 14th I flew down to Las Vegas from Boise. I rented a car at the airport and drove out to Primm, Nevada (a small Casino town on the California, Nevada border, southeast of Las Vegas). The transmitted points we’d received from the transmitter indicated that it had gone down in the mountains, about five miles northwest of Primm. I arrived at my hotel in Primm around 10:30pm. It was difficult to sleep with anticipation of the following day. By five forty-five the next morning, I was wide-awake.

I packed up my stuff and checked out of the hotel. A few days earlier I’d studied a map and found what appeared to be the best way to access the area with a vehicle. My route wound through a large gravel pit on the northern edge of Primm. It continued out into the desert where it turned into a very washed-out two-track that went along an underground gas pipeline. There were a couple of places along the two-track where I wasn’t sure whether or not my vehicle was going to make it. About a quarter mile south of the point that I’d picked on the map for parking, a barbed wire fence crossed the two-track. The fence had been cut and closed back up in the past but I’d left my fencing tools behind when I boarded the airplane in Boise. The fence was only about half a mile south of the original spot I’d picked for starting on foot.

I was feeling pretty good about my early start until, while loading my pack I realized that I’d lost an essential piece of equipment. At some point between the IBO office in Boise and where I had just parked, I had somehow misplaced the cord that connects to the receiver to its antenna. The rest of the equipment I had would be of almost no use without it. I quickly searched through my gear multiple times without finding it. I drove back to Primm as quickly as I safely could on the rough, washed-out two-track. I tried to re-trace my steps as I ran back into the Casino hotel, where I’d stayed. A nice lady at the counter gave me a key to the room and I was extremely relieved to find the cord coiled on the counter next to the TV and microwave cords.

By the time I got back to my start point, the outside temperature seemed to be quickly increasing. Shortly after leaving the car I was starting to worry about the amount of water I was carrying. With the heat, the steep terrain and my hurried pace (trying to make it to the start point before the transmitter began its four-hour transmission cycle), I was drinking a lot of water.

The terrain was much steeper than I’d thought it would be after viewing the satellite images of the area. A few hundred meters from the car a snake rattled out of my path. He served as a good reminder of the things I needed to watch out for. The rock that made up a large part of the steep ridges turned out to be very coarse and easy to grip while I was climbing up. With the ease of climbing, I was able to reach the top of the ridge more than an hour before the transmitter was estimated to turn on.

The first thing I did when I arrived on top of the ridge was find shade in one of the many shallow caves that are formed in the rocks. From my sheltered lookout at the top of the ridge I could hear, every once and a while, what sounded to me like a young raptor begging for food. I’d heard from the biologist who’d come out to look for the transmitter before me that there were a fledgling and adult Peregrine Falcon in the area.

After I’d begun searching, it took me a while to locate the signal coming from the transmitter. While holding the antenna out in front of me, I would work my way out to the ends of the jagged rocks that stuck out off of the main ridge. I went back and forth a couple of times, from one side of the ridge to the other, in an effort to determine which side it was on. The points on our map had indicated that it was most likely located somewhere on the south side of the ridge. I searched for about an hour, without finding a signal.

I was sitting at the top of the ridge, near the start point, trying to decide what my next step should be since I hadn’t heard any signal. It was then that I finally picked up the signal. I was very excited when I heard the first signal strength readout. The transmitter appeared to be located where I’d thought it would most likely be after I’d seen the map. It was also much closer than I’d thought it would be when I first picked up its signal.

Before leaving Boise, Stephanie had warned me about an issue that can arise while operating this kind of equipment in steep terrain. She’d said that the signal could deflect off of cliffs before being picked up by the receiver. This effect could trick the person operating the receiver into thinking that the transmitter was closer or in a different direction than it actually was. Just a few minutes after picking up the transmitter’s signal, the receiver’s proximity read-out was indicating that I was within fifteen meters of the transmitter. It seemed unlikely to me that I could already be that close. Due to how near I was to steep terrain, I assumed that the signal from the transmitter must be bouncing off of the rock in the area. I decided to walk a ways further south. When that didn’t work I tried moving to the east of where receiver had first taken me after picking up the signal.

Each time I walked in a different direction, the antenna indicated that I needed to move back in the direction of where the receiver had given me the highest proximity readout. After about forty-five minutes of walking around, I gave in and started searching the smaller area where the signal was strongest. The only clue that I’d come across up to that point was what appeared to be a body feather. The feather was small and slate-gray in color—obviously not from a curlew.

After a frustrating fifteen minutes of hiking up, down, back and forth across the steep slope, trying to find where the signal was best, I saw what I’d been looking for. Sticking up from among some brown, sun dried grass was a Curlew’s wing. It appeared to me that the bird’s skeleton had been picked clean by a raptor. Even the pad that lies under the transmitter to protect the bird on the bottom had been chewed by whatever predator had eaten the Curlew. Bones and feathers were mostly all that was left of the bird.

The transmitter sat about a foot from the bird’s remains. It was sitting upright on a rock with its solar panels sparkling in the afternoon sun. Because of my assumption that the equipment had been encountering interference, I had ended up searching at least another forty-five minutes longer than would have been required. Before leaving, I took several pictures of the bird’s remains and transmitter then collected the transmitter, metal leg band and plastic flag that was placed on the bird’s leg for identifying her at a distance. While I was picking up the equipment, I found another small feather, the same gray color as the first. This seemed to be good evidence that it was probably a Peregrine Falcon that had eaten our curlew.

I then quickly made my way back down the mountain to make the five-thirty flight out of Las Vegas. As I worked my way down towards the car, the heat rapidly grew more and more intense.

A few hours later, as I was preparing to go through security at the airport, I worried that the luggage scanner might damage the valuable transmitter. When I explained my situation and what the device was to one of the TSA agents I was assured that the transmitter was definitely going to have to go through the scanner, regardless of any damage that might occur. I was relieved the next day when Jay texted to inform me that the transmitter was still transmitting.

A Return to Flat Ranch

I had spent three days in Island Park looking for the transmitter that went down at Flat Ranch, but since it wasn’t transmitting I couldn’t find anything. Then, soon after I returned from Vegas, the transmitter unexpectedly started transmitting again around August third. A few people from the Flat Ranch Preserve went out and where unable to find it, so Jay sent me out with the transmitter-locating equipment to try. This was only my second time using the equipment.

This time seemed to me like it would be much easier. The search area was, for the most part flat and right next the highway, instead of being on steep cliffs like the bird from Primm. The only vegetation over most of the area is very thin grass that stands about a foot tall. As soon as I turned on the equipment it started receiving a signal.

While I was following the signal and nearing the transmitter the preserve manager’s dog walked over and started sniffing at something that turned out to be the Curlews wings. The rest of the bird’s carcass, the bands and the transmitter were there as well. From the time I turned on the receiver it had only taken us about an hour and a half to find the transmitter.

The bird appeared to have been hit by a car traveling on the highway. The highway is about a hundred and fifty meters to the west of where we found the remains of the bird. The skeleton was very broken up and even the plastic flag that had been placed on the bird’s leg for identifying him at a distance was broken. Based on what we observed, we concluded that the two small solar panels on the transmitter must have been covered by the bird’s carcass during the time that it wasn’t transmitting. When we found it, the transmitter was about a meter from the carcass. A Raven or some other predator may have pulled the transmitter away from the carcass to where sunlight was able to reach it.

In closing, though we are very sad to have lost two curlews, we have gained important information about mortality risks to curlews and we’re fortunate to have been able to recover both transmitters for use in 2016.