By Heidi Ware Carlisle, IBO Education and Outreach Director

A Record Year for Banding and Monitoring

In 2023, our hummingbird project rebounded in more ways than one!

During the first year of the pandemic, we had to make some tough decisions. The safety of our team and the public came first, and we regrettably had to scale back our crew and cancel public banding events. In the years since 2020, we managed to get great monitoring data with our core team of volunteers and banders. But as 2023 approached, we carefully devised a plan to recapture the magic of public banding days and rebuild our crew.

We missed having you all there with us to share in the excitement and couldn’t wait to see everyone again!

The Hummingbird Band Making Process

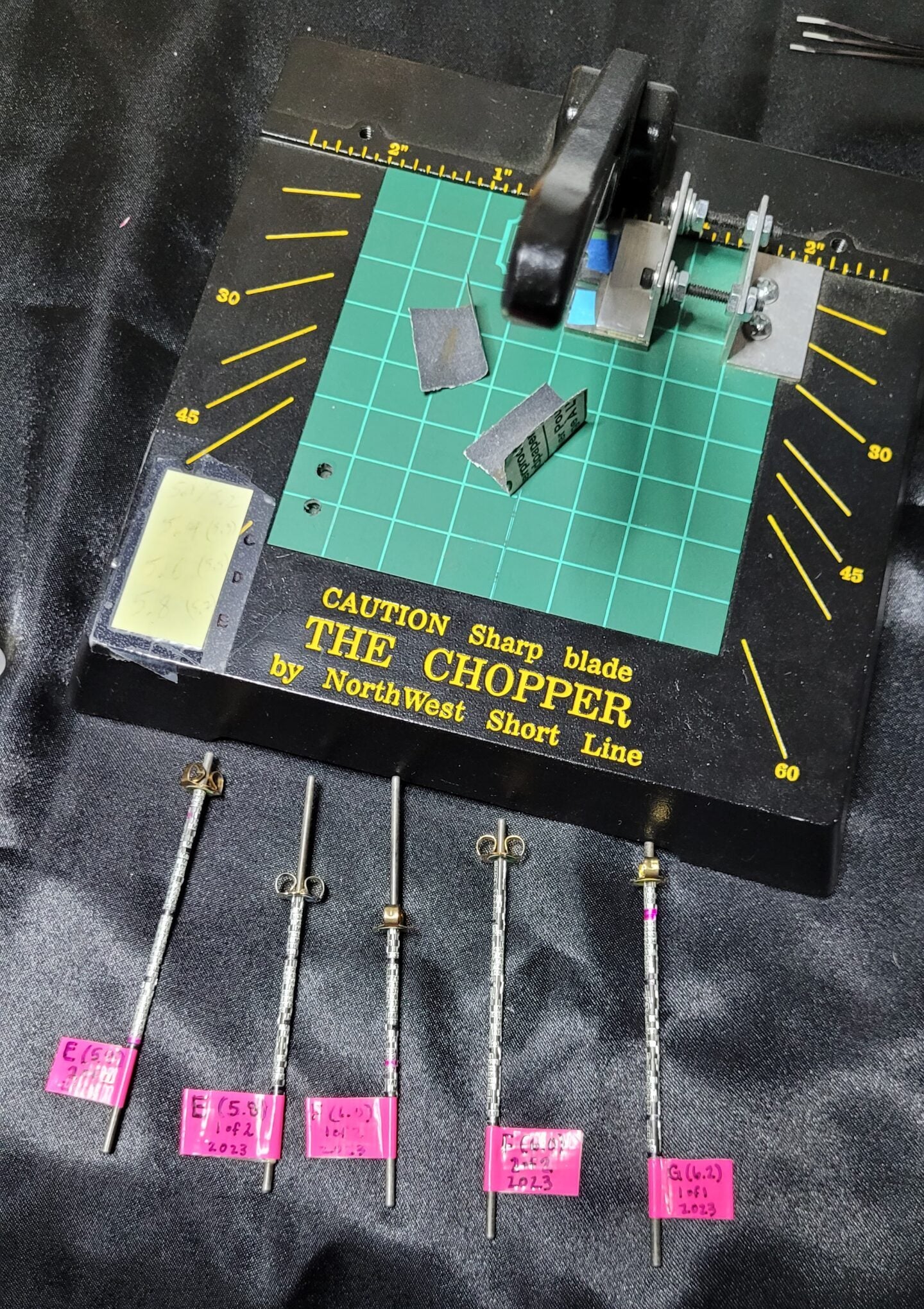

Along with planning for our “return to normal”, we needed to prepare our bands for the upcoming season. Every winter, we invest countless hours creating tiny aluminum hummingbird bands to ensure a steady supply for the summer. Yes you read that right, Heather Hayes carefully chops, sands, molds, smoothes, and organizes hundreds of miniscule hummingbird bands each year. They are too delicate and precise to make in a factory like other larger bird bands.

Every single one is made by hand!

This year we thought we were well on track. I calculated our five-year band usage for our most commonly used band sizes, factoring in the highest annual counts and adding a substantial buffer. It appeared we had enough bands not only for this year but possibly even the next…

…or so I thought!

The spring began with a flurry of activity, with numerous gravid females forecasting a successful breeding season. As the summer progressed, we found ourselves banding an increasing number of Calliope and Black-chinned Hummingbirds.

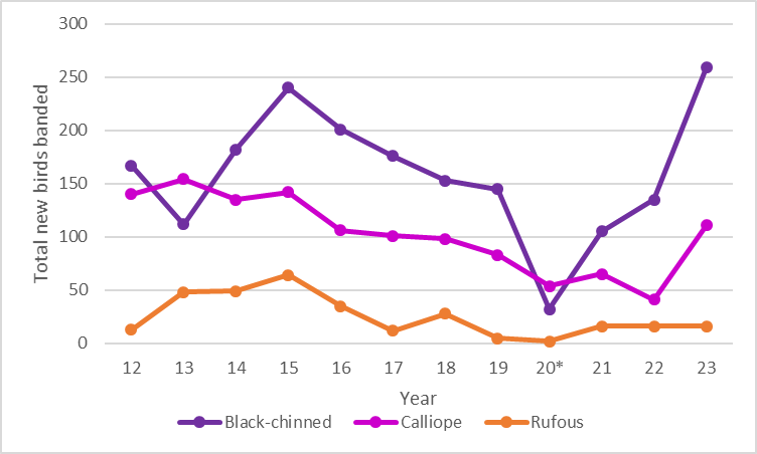

As the numbers rolled in each week thanks to the diligent and speedy data entry of our volunteer, Danette, I started to get a sense that we were banding a lot more than we’d seen the past few years. A quick check of our data up to that point confirmed it:

Only half way through the season we were on track to surpass our best Calliope total in over five years!!

The next banding session we chatted excitedly about the numbers. It seemed they were just not slowing down! We never had our typical end-of-the-day lull that we were used to. However, midway through a banding morning, reality struck. We were about to run out of some key band sizes.

“Ummm…guys we only have like… ten size D bands left!? Can you check the other containers?”

“I only have five size G bands over here”

“Here’s a dozen C bands, and an empty stick of what used to be D’s”

“I have fifteen size F bands left…that’s it!”

Sure enough, it was true; we had burned through the expected band quota and were left with just a few bands in crucial sizes. So, during the following week we made a new batch of bands that I hoped would get us through.

But once again we had a super busy day with lots of young birds and adults coming through on their southbound migration. We had just one monitoring day left, but not enough bands. So I took the band-making kit with me to Boise again, chopping and forming some more.

Watch this video below to get an idea of the meticulous band-making process. A descriptive transcript is available by clicking through to YouTube.

Would we make it?

Well…yes and no. I managed to craft a set of 40 new bands, along with some extra strips that could be fashioned into bands if needed. It was all I had time to make during a busy week of songbird monitoring at Lucky Peak and also the Diane Moore Nature Center.

On the morning of our last day, as the feeders buzzed with hummingbirds before dawn, we knew we were in for a whirlwind.

I quickly showed Danette how to create the tiny C-shaped bands, and as we banded birds, she jumped into action, molding bands of the needed size on the spot. Whew! We made it through our final day, banding 59 birds in total. Thankfully Danette’s band production was able to keep up with the flow of birds!

In the end, we concluded the season with an exciting tally of 395 newly banded hummingbirds and 71 recaptures. This was our second-highest year on record (only surpassed by the 568 we banded in 2015). Our Calliope count of 111 was more than the last two years combined, making it the most Calliopes we’ve seen since 2015.

We also set an all-time record of 259 Black-chinned Hummingbirds!

Public Hummingbird Banding Days

It was a relief to revive our project in 2023. Along with a major recovery in local hummingbird numbers, we recovered on the visitor front as well! We held two VERY popular public banding days where visitors were able to see hummingbirds up close and release them back into the wild after banding.

There’s something truly magical about placing a tiny hummingbird on someone’s fingers, allowing them to feel the bird’s heartbeat.

It’s a powerful reminder of just how special these creatures are and of the important contribution our data collection makes to conservation efforts.

Highlights of the 2023 Season and a Huge Thank You!

In case you missed it on our social media or the local news, we had a few other highlights during the 2023 season: we tied the record for oldest Calliope Hummingbird and banded a rare hybrid Black-chinned x Broad-tailed hummingbird!

Special thanks to our crew this year who made it all happen!

Especially thanks to our “hummingbird hostess”, Jennifer, who allows hordes of bird nerds to invade her home every few weeks all summer long. Without her generosity (including brewing gallons upon gallons of nectar each season) we’d have no project at all!

Trappers: Barb Howard, Christina Garsvo, Lucian Davis, Matt Danihel, Jared Arp, as well as Noah Nei, Ben Shingles, Sarah Dzielski, Aidan Bergam, and CJ Earl.

Banders: Heather Hayes, Katie Powell, Liz Urban, and myself

Data recorders: Danette Henderson, Christina Garsvo, Carter Strope, Tyler Jensen, Carla Wise, Kennadee Earl, Liz Lopez, Mari Wharff, Nicole Bergam, Zoe Bonerbo, Thomas Serrano, Danika Tsao, Ally Turner, Jae Phelps, and numerous staff from the Idaho Fish and Wildlife Office.

Public day support team: Sue Myers and Jen Newlin.

As well as additional help from: Levi Sheridan, Troy Longorria, Nicole Bergam, Erin Schultz, Hailey Hanson, Lisa Ellis, Jaan Koltz, Robert Jaeger, Jaya Smith, Tyler Jensen, Kathleen Hendricks, Ciara Cusack, Laura Harris, and Kayla Bergam

This article is part of our 2023 end of the year newsletter! View the full newsletter here, or click “older posts” below to read the next article.

Make sure you don’t miss out on IBO news! Sign up to get our email updates.