Each fall, we ask our Lucky Peak technicians to share a bit about their field season. This year the crew treated us to some fantastic writing, photography, and illustrations that you won’t want to miss! You can read the whole article, or skip ahead using the following links to read about songbirds, hawkwatch, raptor banding, and owls.

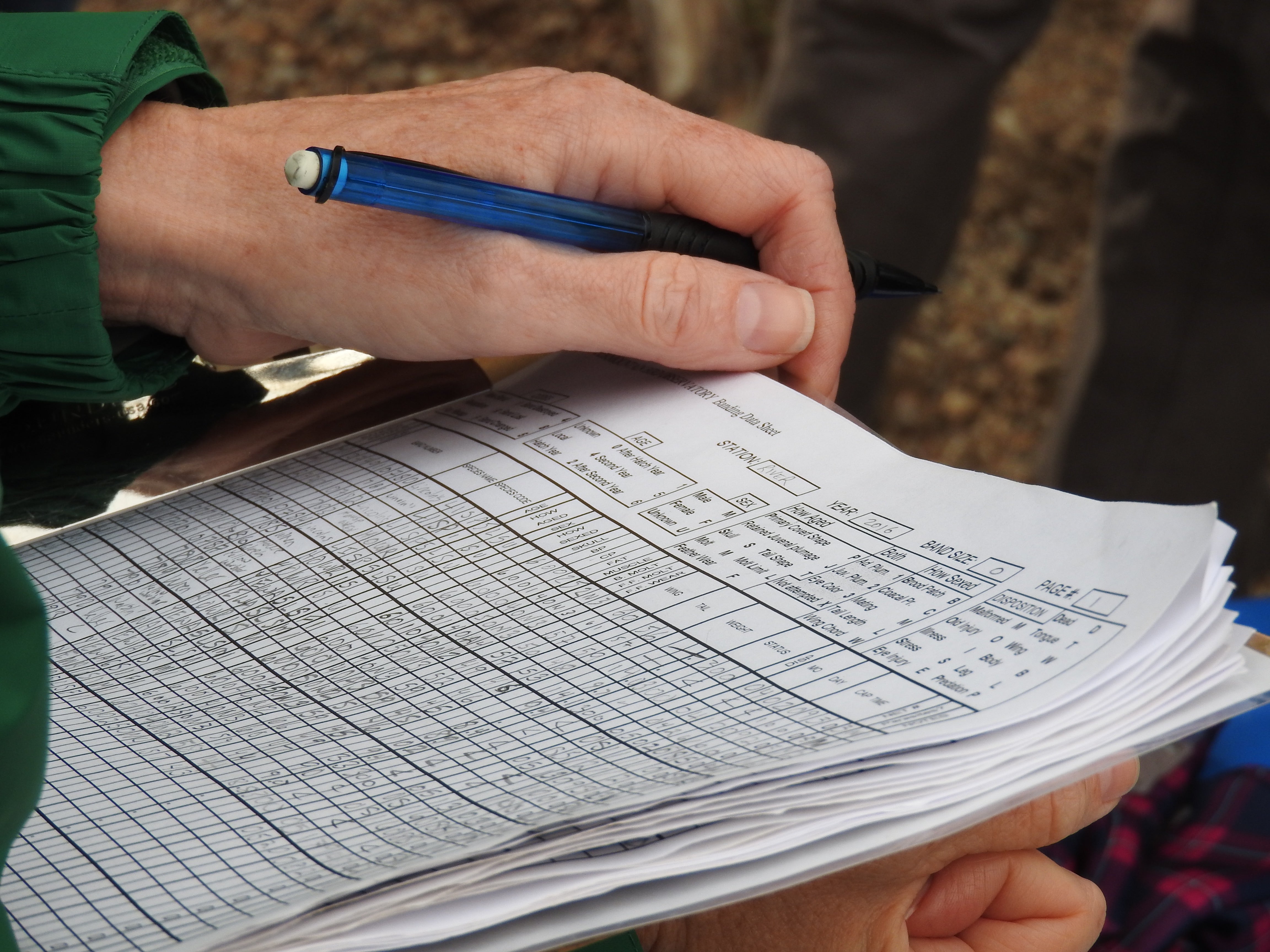

The Morning News

By songbird crew member Rebekkah LaBlue

Songbird banders are the first to arrive on Lucky each season, and the smokey, amber-washed evening of July 14th—pleasantly peppered with the chip notes of soon-to-be migrants, this Easterner’s first-ever breath of intermountain air, and the laughter of five technicians who had no idea just how grateful they’d be to have found each other—set the tone for what was to be a joyful, if ominously warm, autumn.

“Fall banding, in July?”

A question many of us on the crew receive. It may seem counterintuitive, but a variety of factors including species and climate patterns may push some birds to migrate before the breeding season ends for others. Our first net runs on the morning of July 16th were busy: filled with still-brooding Cassin’s Vireos and doting Lazuli Bunting dads, not to mention a few Black-headed Grosbeaks and hummingbirds already fattening up to leave.

The Peak buzzed with other activity, too!

For some time our crew cherished its “Snake Streak”: tallying the number of consecutive days in which we sighted at least one individual scaled neighbor around camp (most often Great Basin Rattlesnakes, Rubber Boas, and Gopher snakes).

The entire first week of banding—which included an 82 bird day—seeded high expectations for the season: a sentiment that may ring familiar from last year’s Lucky Peak recap. Indeed, our researchers wonder if warming weather patterns, drought, fire activity, and continuing residual effects from the 2020 songbird mortality event in the southern Rockies may have conspired to set a new record low at Lucky for the second year running, with 3,718 new individuals banded. While station capture rates and the stability of bird migration routes fluctuate annually, the question rang in our crew’s ears as the months came and went: is this a new norm?

Only more study and collaboration will help us paint a holistic picture and make firm determinations.

One of the more difficult jobs of a bander is to hold optimism and skepticism in their hands at the same time. So, as the hard work of keeping a finger on the pulse of our bird populations continues, we must also do the hard work of emphasizing the passion for what we do, including the 59 species we were privileged to meet, and the nearly 400 visitors we shared with this season.

Despite a low capture rate, a number of extra-feathered encounters, exciting birds, and learning opportunities kept our crew in good spirits.

While averaging 20-40 bird days through July and August, we hosted an honorary sixth technician: a curious Yellow-bellied Marmot that, like clockwork every morning, would crawl atop the tallest stump in camp and watch us band for several hours.

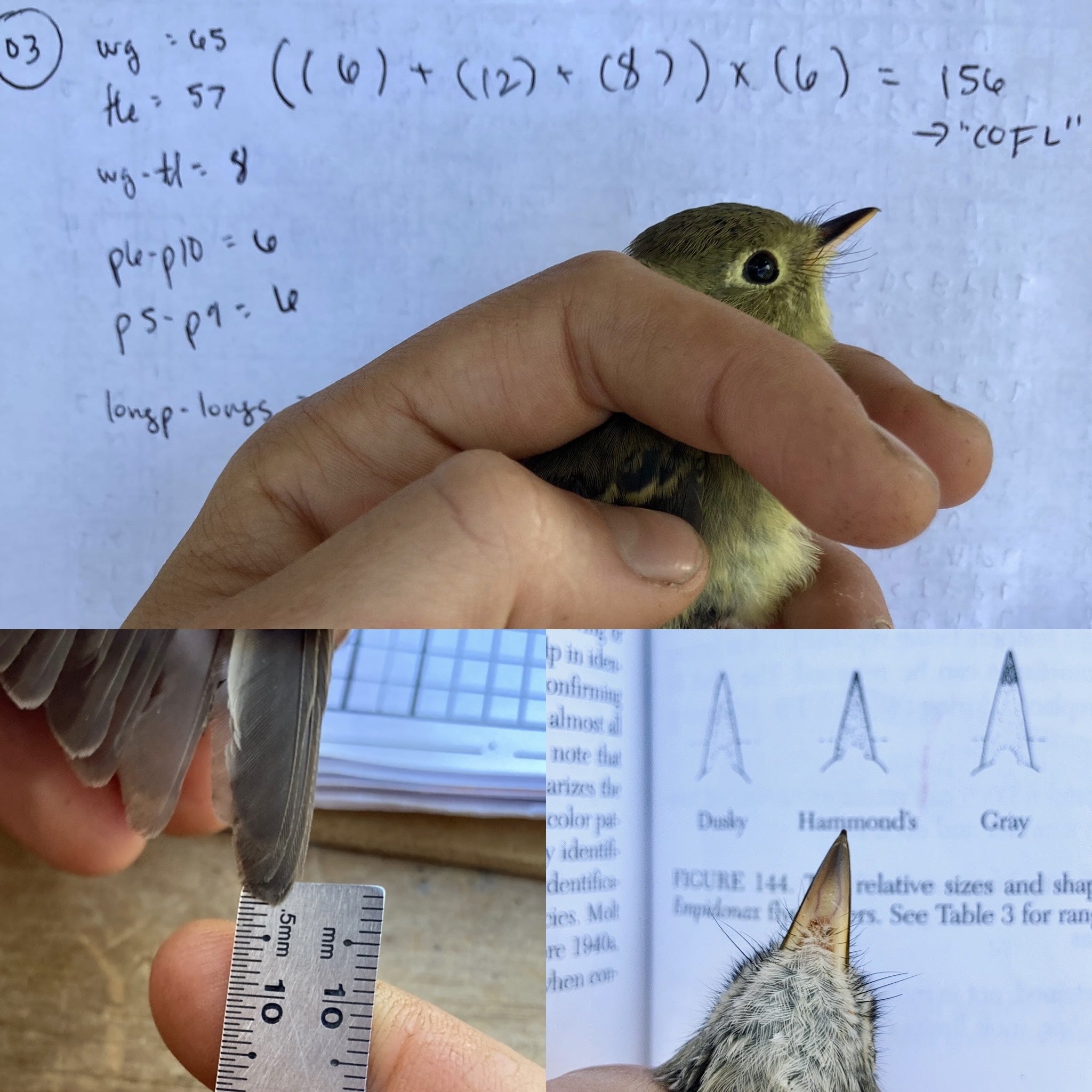

A few welcome challenges for crew members early in the season included eccentric molt limits among buntings and sparrows, and “flycatcher boot camp.” Many birders are aware of the trials and tribulations of identifying Empidonax flycatchers in the field.

However, some may be surprised to learn that the task can be nearly as difficult even with the birds in hand!

One of the techniques we use is to measure the relative lengths of certain flight feathers—the differences separating species are just millimeters. If this process doesn’t sound tedious enough, just wait until you meet “math bird”: the Western Flycatcher! Per Lucky protocol, we lump Pacific-slope and Cordilleran Flycatchers in our data—two species once lumped in official taxonomy—because the mathematical formulas used to tell one species from another result in values with exceptional overlap. One thing is for sure, you better brush up on PEMDAS before handling these birds!

With the arrival of some (slightly) cooler weather in September, we welcomed a few of our more iconic fall migrants and winter residents: White-crowned Sparrows, Dark-eyed Juncos, Townsend’s Solitaires, Yellow-rumped Warblers, and Ruby-crowned Kinglets, though many in surprisingly low numbers.

In addition, we saw an influx of notable birds, including the station’s first ever Ovenbird on September 5th!

Equally exciting was the station’s first intergrade Northern Flicker on September 21st!

The songbird crew also banded the station’s 2nd Williamson Sapsuker and 15th American Redstart, not to mention the station’s 6th Red-eyed Vireo. And then lightning struck twice:

We captured not one, but two Canyon Wrens and two Steller’s Jays this season!

Also in September, two members of the songbird crew geared up for their North American Banding Council (NABC) certification exam, and we’re proud to say each passed at their desired level. Congrats to newly NABC-certified Bander Linda and Trainer Rebekkah!

On October 8th, we captured 84 birds: our biggest day of the season; 75 of these birds were “Rickis” (stemming from their 4-letter alpha code RCKI), as we lovingly call our Ruby-crowned Kinglets! The kinglet crush continued reliably through our season’s end in mid-October, when we finally began to see a much-anticipated push of junco arrivals. A handsome, after-second-year male Oregon Junco was our final bird banded for fall 2022.

It will take time to tease the story from this season’s data, but the five of us are humbled to have been a part of the Lucky story, contributing to the important, multilayered work of bird conservation in the West. Thanks to our wonderful visitors and volunteers, as well as IBO’s technicians and permanent staff for an unforgettable season. Until the next trip around the sun!

The Afternoon News

Hawkwatch

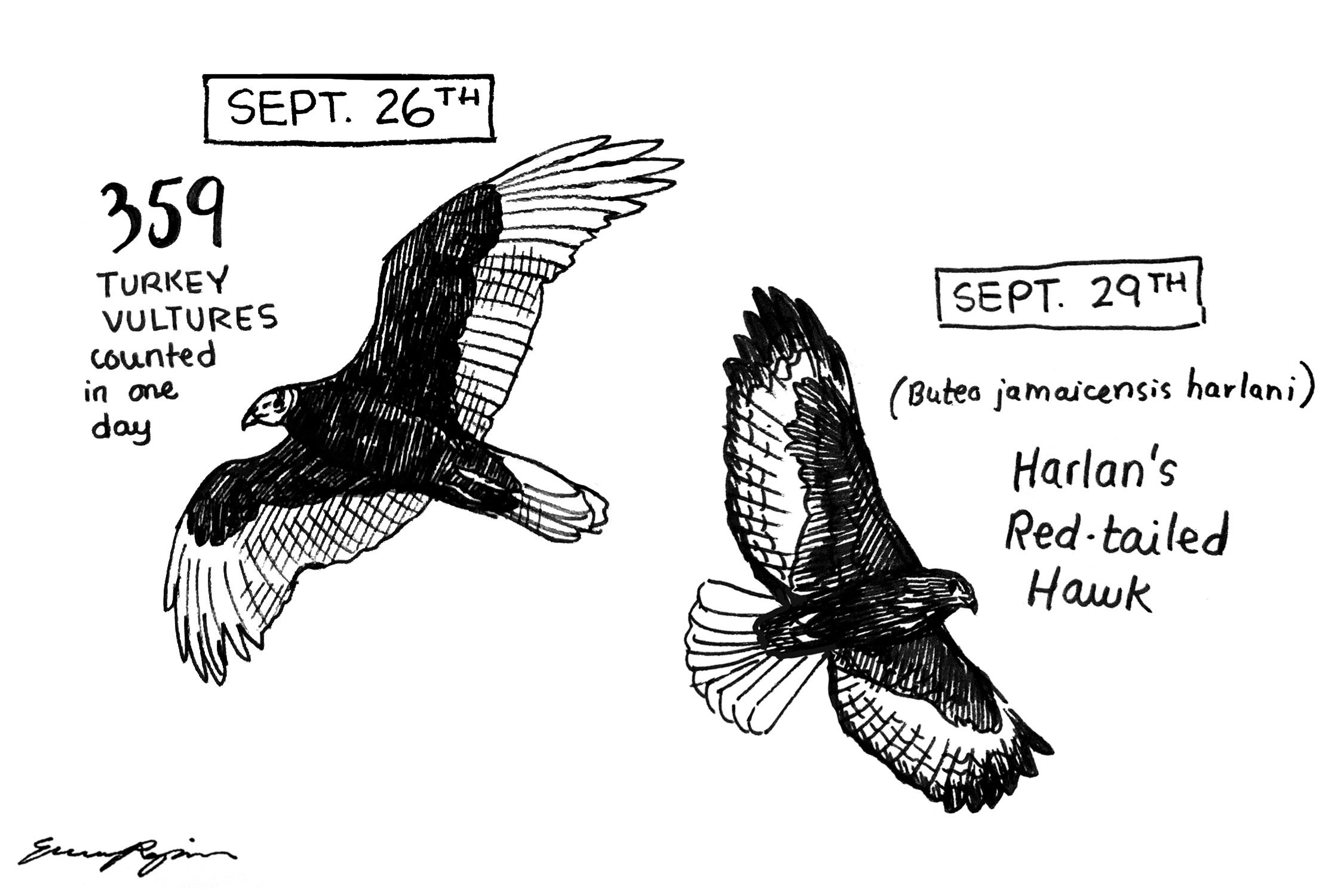

By hawkwatchers Isaac Grosner and Emma Regnier

Every day from August 15th until October 28th, a dedicated crew of hawk watchers stood atop Lucky Peak and scanned the skies from mid-morning until the golden afternoon sun started to set. This year marked the 28th year of monitoring the raptor migration at Lucky Peak, and a very hot and smoky August gave way to an unusually warm and pleasant September and October.

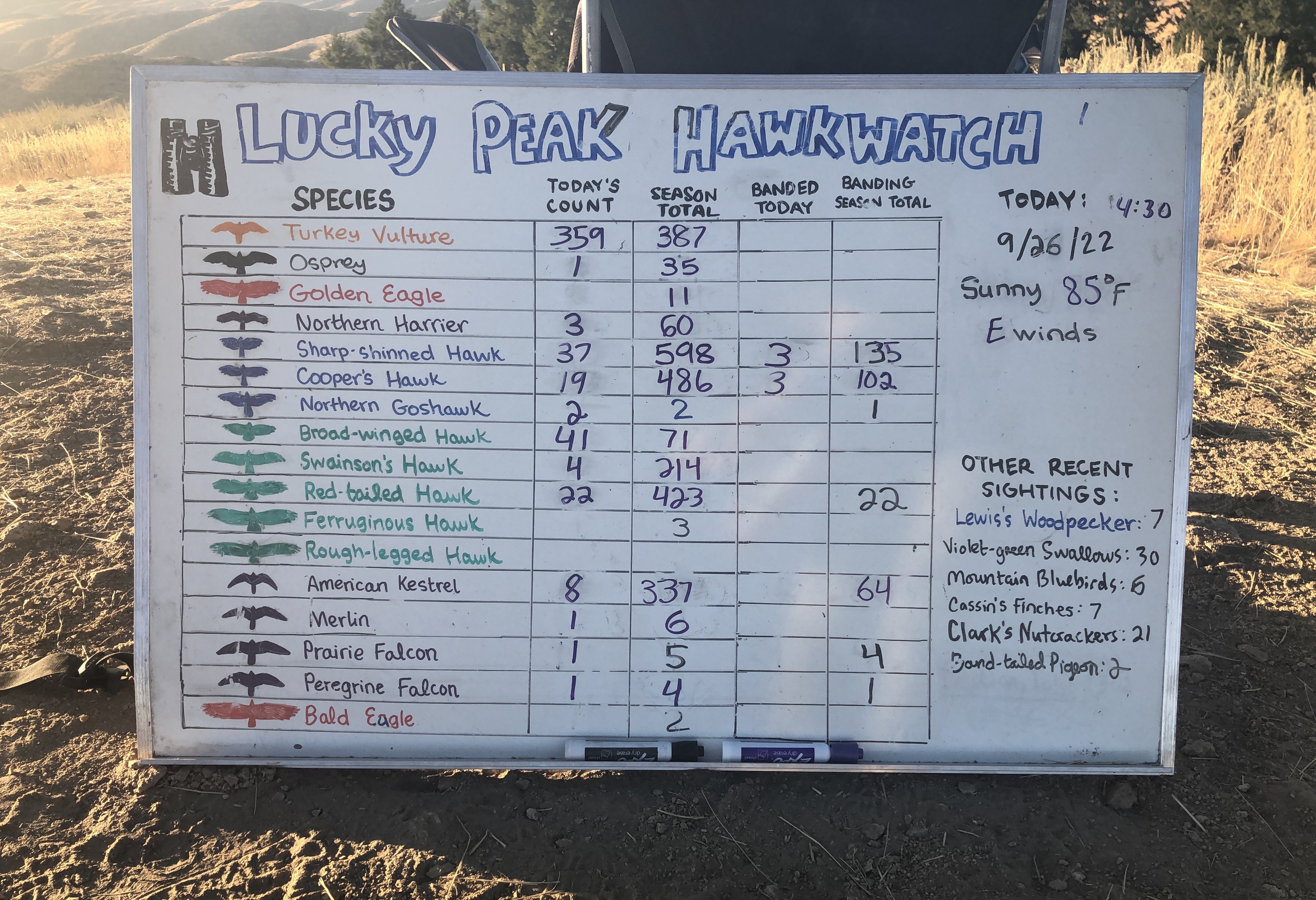

Over the course of two and a half months, we counted a total of 5,504 raptors of 18 different species!

While the season total was below the 28-year average of 6,429 raptors, every fall is filled with surprises and this year was no exception.

Whether it was the warmer weather, wildfires, or another reason unbeknownst to us, the raptors weren’t in any hurry to start their migration. But once they started moving, they moved in force! It all came together on September 26th, when we counted a whopping 522 raptors of 13 species, including a spectacular show of hundreds of Turkey Vultures kettling together in the cool autumn breeze.

There were many other special moments throughout the season. We counted three Harlan’s Red-tailed Hawks, which are a rare and beautiful subspecies that breed in Alaska and NW Canada. A dark morph Harlan’s Hawk can be identified by its striking nearly-black body feathers, pale flight feathers, and white tail. They are an unusual sight during fall migration at Lucky Peak, so to count three this season was a real treat.

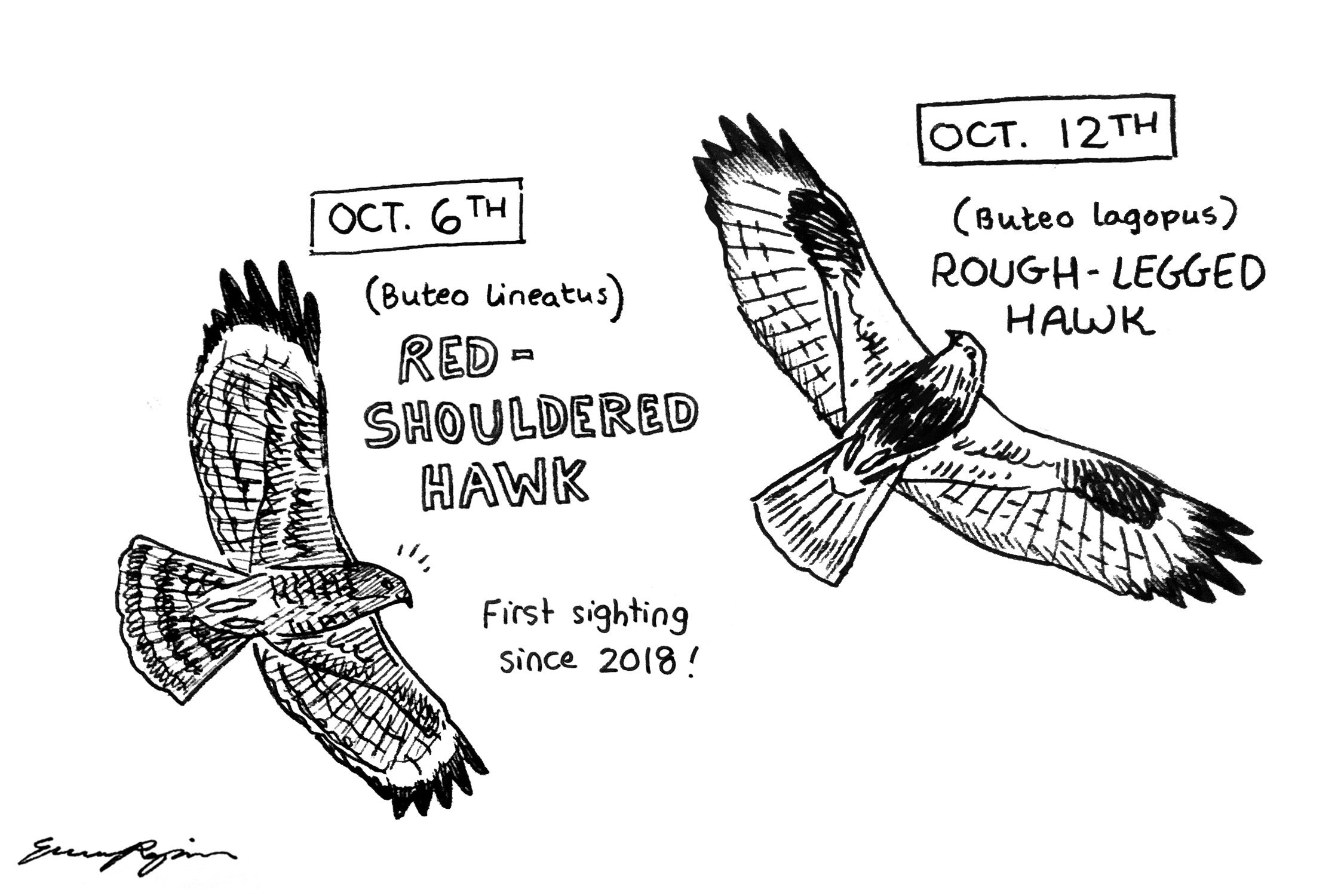

Another exceptional bird we counted this year was a Red-shouldered Hawk-the first sighting since 2018!

Our incredible volunteer hawkwatcher, Kateri Bilay, was the first to spot the unmistakable pale crescent-shaped markings in its wings as it soared over the peak on its journey south.

On October 12th we welcomed the arrival of the first (and only) Rough-legged Hawk of the 2022 season. These hawks breed in the Arctic Circle, and are some of the last hawks to migrate through Lucky Peak. The first “Roughie” of the season is a sure sign that winter isn’t far behind. A fan favorite bird of the Raptor Crew, we all jumped for joy when we spotted the dark carpal patches on the underwings of this pale juvenile bird as it circled up in the west above Table Rock.

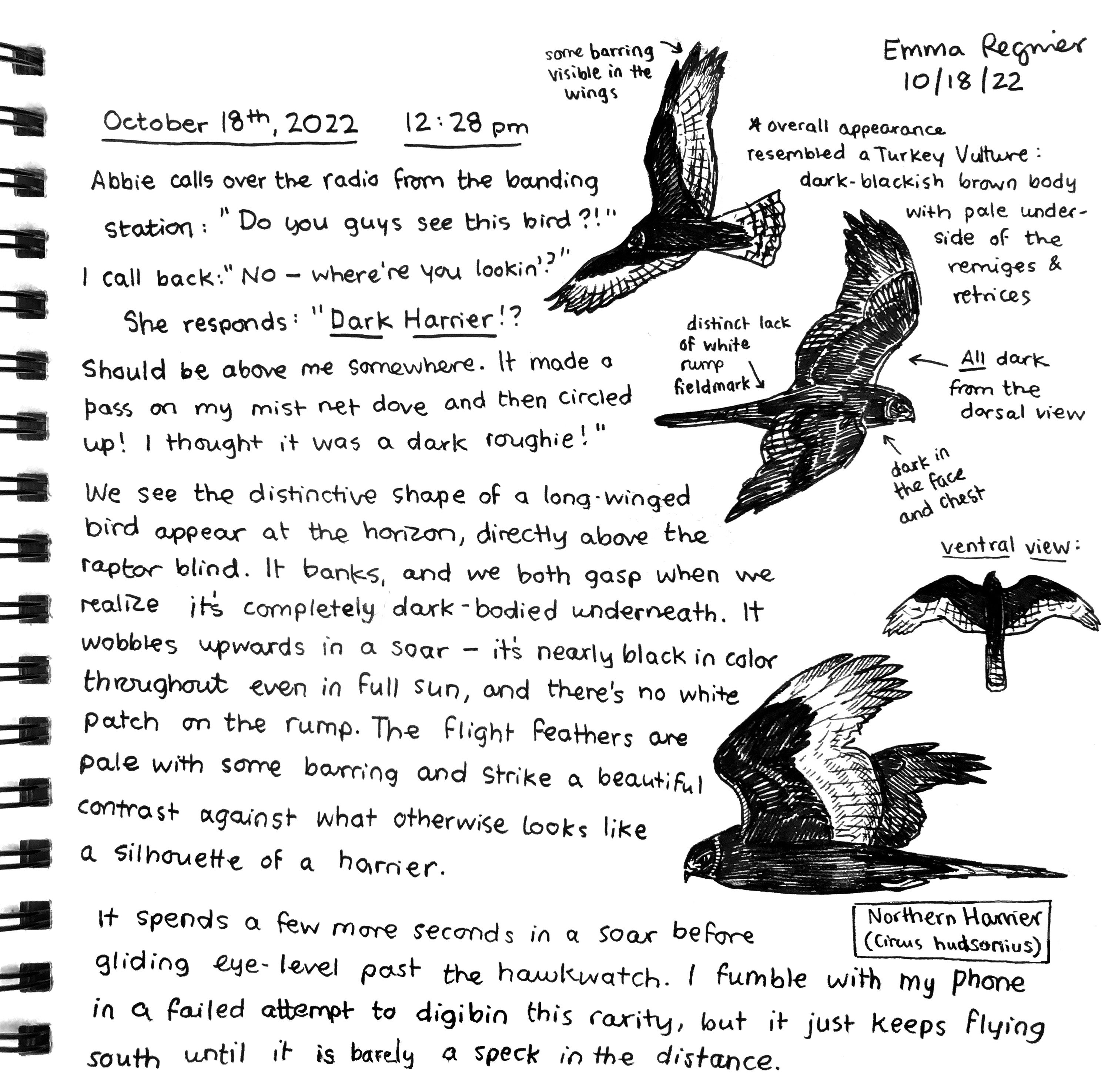

Then, about a week later, Hawkwatch was stunned by an exhilarating encounter with a mysterious melanistic Northern Harrier!

The distinctive long-winged and lanky bird first appeared directly above the banding station, but when it banked, we realized it was nearly black in color throughout – even in full sun. Lacking a white patch on the rump, its flight feathers were pale and struck a beautiful contrast against what otherwise looked like a silhouette. Only a handful of sightings of melanistic Northern Harriers have ever been documented!

The biggest highlight of the year was undoubtedly the Broad-winged Hawks! These hawks are small Buteos that don’t actually breed in Idaho, so the best time of year to see them is during the fall migration, and there’s no better place to see one than at Lucky Peak! The season average for Broad-winged Hawks is 35.

But this year we counted a record-breaking 146; all but blowing away the previous season record of 84!

To make it even wilder, we had one day where we counted 42 in a single day! It was a joy to watch these elegant little hawks fly by on their way to the tropics.

Just because we are hawk watchers doesn’t mean we don’t appreciate the smaller birds, too! Even during slow mornings, we thoroughly enjoyed seeing large flocks of Lewis’s Woodpeckers, Western and Mountain Bluebirds, and Clark’s Nutcrackers. A few Evening Grosbeaks, Northern Flickers, and a Black-backed Woodpecker kept us company, and the surprise appearance of two Band-tailed Pigeons was a delight.

All in all, we had a blast at Hawkwatch, and it was a privilege to get a front seat to the spectacle that is raptor migration!

Many thanks to our intrepid Hawkwatch crew: Emma Regnier, Isaac Grosner, Jeremiah Sullivan, and Kateri Bilay. We hope you’ll join us up at the peak next year!

If you enjoyed the nature journal illustrations throughout this article by Emma Regnier, be sure to check her instagram page and other amazing work here. She also designed an incredible Lucky Peak project t-shirt and they are available for purchase in our IBO merchandise shop– these make wonderful gifts for the bird lovers!

All proceeds go directly back into our outreach and education efforts!

Raptor Banding

By Abbie Valine, Lucky Peak Raptor Bander

The hardest thing for me to get used to while trapping at Lucky Peak was the view. Coming from the Midwest, how was I supposed to concentrate on the birds when there were actual mountains right in front of me?

As it turns out, it’s a good thing the view is nice, because the raptors took their sweet time arriving.

We had a very slow August, with only 40 birds banded at the Lucky Peak station. September also started off slow, but by the middle of the month the pace of migration picked up and things got busier. This push of birds continued throughout early October.

But unseasonably warm temperatures and unideal wind conditions seemed to discourage many raptors from moving the last few weeks of October, and we ended with a total of 510 birds banded.

Although the season as a whole was below average for some species, we banded higher-than-average numbers of Red-tailed Hawks, Cooper’s Hawks, Prairie Falcons, and Peregrine Falcons. But despite the slow start, the late-night fallouts of hunting kestrels, the long-anticipated arrival of the first Merlin, the undulating display flights of the resident pair of Golden Eagles, and every single Sharp-shinned Hawk we saw made the season so worth it.

One of my favorite days of the season was September 8th, a day of blustery west winds. Small birds like Sharp-shinned Hawks and American Kestrels were getting buffeted about in their attempts to come into the station, and even the bigger birds like Red-tailed Hawks were struggling in the strong winds.

Suddenly, a Prairie Falcon appeared in front of me, and it was like there was no wind at all!

Her strong, angular wings allowed her to carve through the gusts with perfect mastery, and I was overjoyed to capture my first ever Prairie Falcon, a young female.

Another exciting event happened the night of October 3rd, when we captured an adult Great Horned Owl at the station, likely one from the resident pairs that we heard frequently near camp throughout the season. Since everyone on our crew had rotating days off throughout the week, it was rare that all of us were on the mountain on any given day. However, all 11 of us were present and got to experience the magic of this owl together.

It was a night that none of us will forget!

The Evening News

By the Lucky Peak Owl Crew

Kevin García: In terms of owls caught, the 2022 season fell short of IBO’s owl banding average. We banded a total of 208 owls during the season compared to the 455 individuals banded in 2021. The beginning of the season was very challenging since we banded a single owl or none for several nights. Slow banding days are a nightmare- just ask your nearest bander! One owl during a 10 hour night will definitely test your spirit.

Luckily for me, Lucky Peak provides an excellent opportunity for visitors to camp at the station to experience owl banding!

I took full advantage of all my free time in between net checks and shared everything I learned about our two study species, Flammulated and Northern Saw-whet Owls with the public.

There is a rumor that wildlife biologists dislike public engagement. It’s not true. The education component of this station was one of the biggest reasons I applied to band owls with IBO and I truly enjoyed it!

Some of my most memorable experiences were seeing the public react to all the owl facts we shared with them. Owls are among the most cryptic bird species to observe in nature, especially our two study species. For this reason we made sure every visitor got to see the birds as they were banded.

Not only did they get a chance to see the owls up close, but they also received an education about the purpose of banding and owl anatomy as we collected data on each bird. The public enjoyed seeing every step of banding.

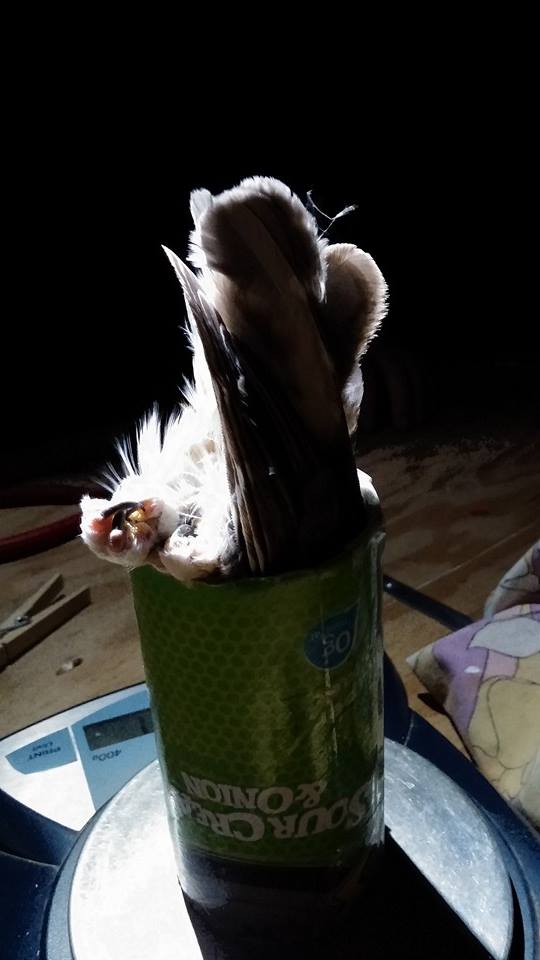

You could hear the “WOW!”s as we blew on the bird to check for fat and also the composed laughter as we placed an owl in a tube to determine its weight.

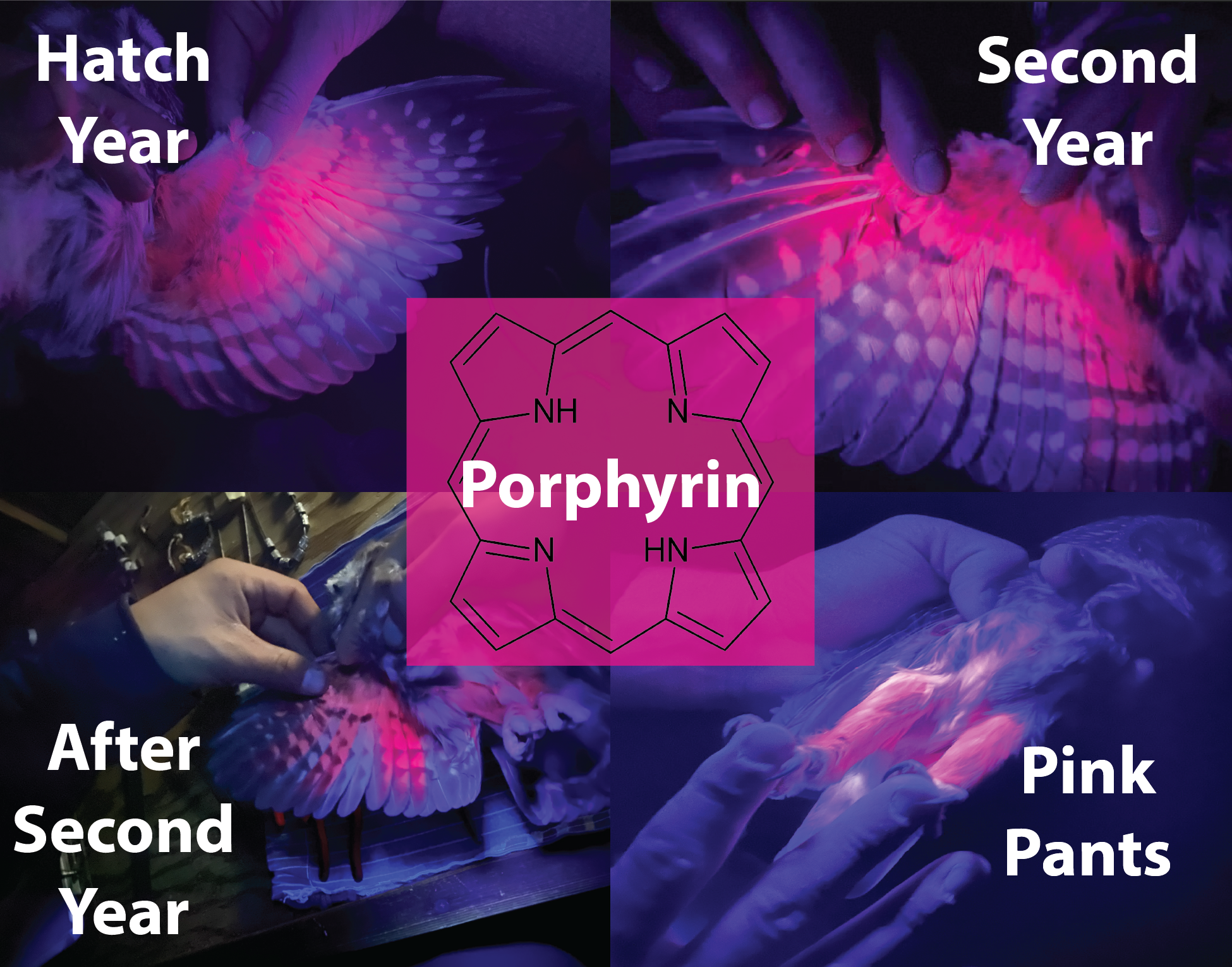

The biggest “OOOH’s” and “AAAH’s!” occurred when we exposed the beautiful fluorescent pink feathers of owls under our UV light. Owl feathers contain a fluorescent pigment called porphyrin. This compound helps us determine the age of an individual based on its concentration in owl feathers.

Banding and mist-netting typically comes with the fun element of surprise. You never know what may end up in our nets and this season had plenty of “chance” visitors! One surprise was a hatch-year Long-eared Owl, and believe it or not, they’re a lot smaller than you’d imagined they would be. We also had some “furry” surprises frequent our nets-Northern Flying Squirrels! These common visitors certainly provided a challenge as we had to remove them from the nets with thick gloves on.

This nocturnal species may be cute, but they’re a headache since they often bite their way through the net!

But the biggest surprise of the season was seeing a Great Gray Owl!

YES!! A magnificent Great Gray Owl was caught in one of our nets, but it managed to fly out about a millisecond before I could retrieve it.

I shed a tear that night.

As the season progressed we began to band more birds. By late September we were banding in the double digits per night. Our highest number was a 16-bird night. The season kept that steady pace until mid October. Then the temperature dropped, the public stopped visiting and the owl migration slowed down. Regardless of the total number of owls we banded, it was a memorable season.

It was a dream to work with such beautiful species and to contribute to IBO’s research at Lucky Peak along with my peers!

My highlight of the season was the opportunity to expose the public to the owls and our research. I once visited a banding station and a few years later I had the opportunity to band there. I am confident that our educational effort this season has inspired many visitors to become birders and a few to work in wildlife conservation in the future. Hoot-Hoot!

Lisa Viviano: Taking on the night shift can seem like a daunting task, especially for the first time. Living and working on the exact opposite schedule as everyone else, I oftentimes felt much like a space cadet stationed on a far off planet, but I can say with certainty that this unconventional lifestyle isn’t all bad.

In fact, many benefits and unexpected skills can be gained from operating on a nocturnal schedule.

Staying up late is one thing, but deliberately staying up every night until sunrise is something entirely another. Going against my body’s natural tendency to rise in the morning taught me self-discipline, as there are fewer/less obvious cues on when to wake, eat, and sleep. Moreover, in the dark I couldn’t see my surroundings in the way I was typically used to.

My headlamp, however, allowed me to see something more and perhaps most crucial: eyeshine.

This phenomenon is caused by a mirror-like membrane behind the retina of many animals (tapetum lucidum), which particularly helps night-hunting animals to see more effectively at night. By picking apart details such as color, distance between the eyes, and apparent height from the ground, I was able to identify a deer versus a bear or mountain lion without seeing the figure itself.

On a related note, I also learned how to use bear spray. Many people are (justifiably) fearful of a walk in the woods at night.

But watching the sky switch through various shades of blue and black as the moon cycled through its phases attested to the fact that a considerable amount of beauty exists in working the night shift.

Though the biggest reward by far was sharing a wide-eyed stare with the feathery creatures we captured and studied. Flammulated and Northern Saw-Whet Owls are among the smallest owl species in North America.

They prove to be very hardy as they migrate thousands of miles north and south of Idaho in pursuit of better food sources.

The data we collect contributes to a long-term study on their migration while helping other researchers understand their population trends and life history. Each bird we catch is fitted with a lightweight band which contains a unique code so individuals may be identified when recaptured. In essence, banding helps us reveal interesting and valuable details about bird migration and ecology in a way that can be shared and pieced together within the science community.

This article is part of our 2022 end of the year newsletter! View the full newsletter here, or click “older posts” below to read the next article.

Make sure you don’t miss out on IBO news! Sign up to get our email updates.