Techs from each of our three projects wrote about their time at Lucky Peak this season, and the data we collected. Read the whole article below, or skip ahead using these links to read about songbirds, diurnal raptors, and owls.

The Morning News from Lucky Peak

By: Kyle Lima

We had a very productive year in 2018 banding nearly 6,000 new birds and having the most diverse year in Lucky Peak history, followed by a very unexpected low in 2019 with only 4,347 new bands. So, we had no idea what to expect this season. Fortunately, the 2020 season did not follow the trend, and turned out to be one of our highest seasons: even surpassing the record-setting 2018 season! We banded 6,668 new birds (well over the average of about 5,200 new bands), recaptured 762, for a total of 7,430 birds. You can see our daily observation data for this season on eBird.

We banded 60 species including some unexpected, rare species such as Tennessee Warbler, Black-throated Gray Warbler, Black-and-White Warbler, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, Green-tailed Towhee, Bushtit, and Varied Thrush (which happens to be the third year in a row now that we have caught this species).

The unnervingly slow 2019 season left us with many concerns regarding the status of some migratory bird populations.

However, 2020 brought new hope as many of those species’ totals were equal to or higher than the long-term averages! Some warblers that were worryingly below average last year, such as the Yellow-rumped Warbler, Wilson’s Warbler, and Townsend’s Warbler, were all about average this year. We even broke the single-day record of Wilson’s Warbler with 21 banded on September 1st!

This season also saw a skyrocket in numbers of Orange-crowned Warbler and Ruby-crowned Kinglet (both of which were scarily below average in 2019), setting a new Ruby-crowned Kinglet record with 2,193 banded in one fall (the average is ~1,000)!

Looking at age ratios in migration data is useful. Because birds can alter migration patterns year-to-year, it’s important to determine whether the population did indeed increase, or whether more birds simply chose to take the route past our station. In 2019 when kinglet numbers were low, only 88% of the birds were young-of-the-year (compared to our long-term average of 91%). In 2020, 93% of the kinglets were young-of-the-year! By comparing the percentages of hatch-year birds we can conclude that the difference in numbers couldn’t have been caused by a simple change in migration routes. We can see that Ruby-crowned Kinglets had a very poor breeding year in 2019, and an extremely good breeding season in 2020!

On the other side of the coin, we did see some drops in certain species from last year. In 2019 American Robin was a commonly caught species with a final count of 42 banded but dropped to a low of only 6 this year, far below the average of 26. Townsend’s Solitaire (always a variable species at our station, ranging from 1 to over 100 per season) saw an incredible year in 2019, nearly tripling the average of 35 birds, a stark contrast to the 18 we banded this year. The Dark-eyed Junco happened to be one of the most captured species in 2019 with an impressive total of 1,019. This season they were slightly below average with 442 individuals (avg. of 510). This is not necessarily of concern considering that the numbers captured at Lucky Peak are largely impacted by the variable timing of their migration, and this year the peak happened to be after our last banding day. In 2019, it seemed Juncos began migration earlier than usual, explaining the totals that were double the average.

One common trend between last year and this season is the lower than average totals of Spotted Towhee. In 2019 we captured only 114, and this year we banded 122 whereas the average is 188. This is not of immediate concern considering the above average total in 2018, but maybe something to keep an eye on in future seasons.

Other notable aspects of the 2020 season…

Not only did we see most of those concerning species return to average totals, we also captured notably more than the average for 19 species including White-crowned Sparrow, MacGillivray’s Warbler, Nashville Warbler, Lazuli Bunting, and Hermit Thrush among many others. We banded an exceptional number of Red-breasted Nuthatch (269 to be exact, compared to our long-term average of 67), indicating an irruptive year for the species (read more about irruptions here!).

Additionally, it was a great year for hummingbirds, especially Calliope and Black-chinned Hummingbirds. It was also an incredible year for sparrows! We banded 7 species with 4 of those showing above average totals (66 Brewer’s Sparrow, avg. of 20; 12 Lincoln’s Sparrow, avg. of 2; 9 Song Sparrow, avg. of 4; 7 Savannah Sparrow, avg. of 1). Only 5 out of the 60 species caught this season showed notably lower than average totals, including Yellow Warbler (174, avg. of 292), Western Tanager (136, avg. of 217), Golden-crowned Kinglet (12, avg. of 40), and the formerly discussed American Robin and Spotted Towhee. Only time will tell if these are the beginning of long-term trends, or just natural variation. Check back next year for updates on these species and more!

The Afternoon News from Lucky Peak

By: Evan Buck

The 26th year of our standardized raptor migration count from Lucky Peak was marked by many days of poor visibility due to smoky conditions from the region’s many wildfires. Despite the difficult viewing conditions, a total of 5,109 migrating diurnal raptors were counted over 562.75 hours between August 15th and October 28th. This year’s count is well below the 26-year average of 6,501.3 migrants but above average for observation hours possibly thanks to excellent weather at the end of the season.

2020 was the second year of an August 15th count start, earlier than the typical August 25th, with the objective of capturing the beginning of migration and recording more data on earlier-migrating hawk species. With this jump start to the season we tallied a well above-average count of Swainson’s Hawks: 320 individuals, up from the 26-year average of 117.

Lucky Peak standardized raptor migration count: 2020 compared to the 26-year average.

Despite the low overall count, a few species had above average counts including 11 Rough-legged Hawks (26-year average = 6.0) and nine Ferruginous Hawks (26-year average = 4.2).

However, we counted notably low number of several species including only 713 Turkey Vultures (26-year average = 1323.5), 678 American Kestrels (26-year average = 1018.4), and 795 Red-Tailed hawks (26-year average = 1106.3). The low Red-Tailed Hawk count is especially interesting considering we banded a record 70 individuals of this species in 2020, which is over twice the long-term average.

Then the Lucky Peak Crew really struck gold…not once, but TWICE!

Also above average for 2020 were captures of Golden Eagles. IBO crews were able to band two of these regal monarchs! These captures were particularly exciting as we had not banded a Golden Eagle since 2014.

And the 2020 migratory surprises didn’t stop there…

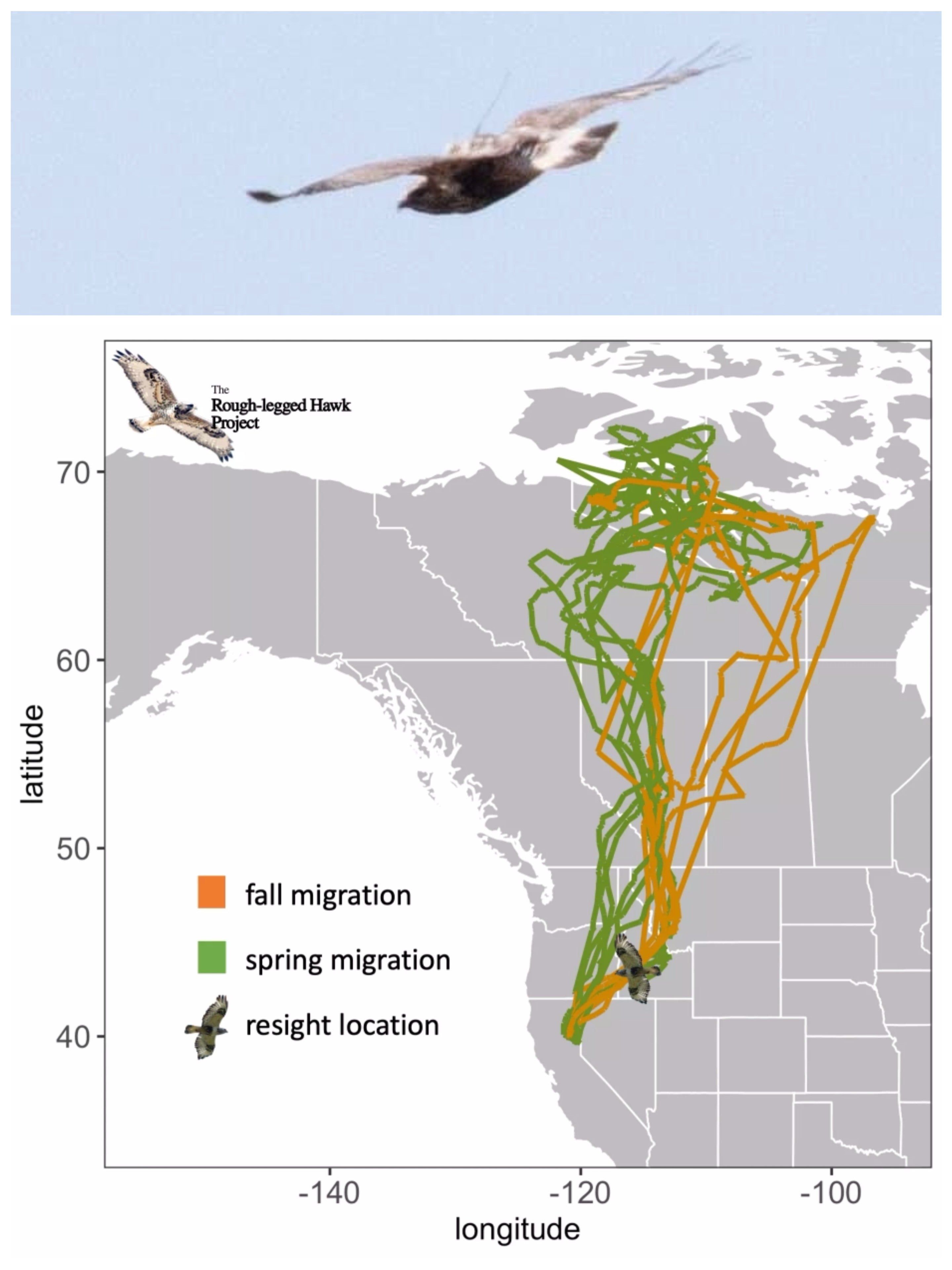

Three hawks that had previously been marked by other researchers were documented by IBO biologists in 2020! The first was an adult Red-tailed Hawk with red patagial (shoulder) tags originally marked at the Portland, Oregon airport; next was a second-year Red-tailed Hawk captured by our banding team originally marked by Golden Gate Raptor Observatory in August of 2019 ; and the final documentation was of a female Rough-legged Hawk with a backpack transmitter originally marked in January 2014 in Quincy, California. This Rough-legged Hawk passed Lucky Peak while migrating from her breeding grounds in Victoria Island, British Columbia, to her California wintering area. What’s even more exciting is that this bird was a part of our colleague, Neil Paprocki’s transmitter study and has been tracked now for 7 years! For more information on this bird and other cool “Roughie” research, check out the Rough-legged Hawk Project.

It is these kinds of encounters that are helping us piece together the puzzle of raptor migration in western North America!

Raptors are not the only birds that fly past Lucky Peak in the fall. In 2020, hawk counters had several notable non-raptor observations. Some of the highlights were three Black Swifts in early September, a Pinyon Jay in October, and large numbers of northbound Red-breasted Nuthatches (over 115 in one morning!). Many thanks to our crew of 2020 hawk counters including Evan Buck, Carly Gilmore, Solai Le Fay, and Sarah Scott!

The Evening News from Lucky Peak

By: Savannah Stewart

The owl season at Lucky Peak started off slowly this year. Whether it was the wildfires or the unusually warm temperatures, it wasn’t until the end of September that we started seeing owls move through in considerable numbers.

A slow start never fails to make us nervous, but luckily our feathered friends were just running a little behind!

The end of September saw a strong push of Flammulated Owls and icy weather in mid to late October brought a wave of Northern Saw-whet Owls south. We banded a total of 46 Flammulated Owls this year, most of which were caught in the last 2 weeks of September (a fairly average year). We banded 491 Northern Saw-whet Owls: 283 Hatch-Years, 1 After Hatch-Year, 154 Second-Years, and 48 After Second-Years. Of these, 295 were female, 63 were male, and 133 were unknown.

A very exciting night in early October brought us several Northern Saw-whet Owls, the last Flammulated Owl of the season, and… a Long-eared Owl all in the same net run!

This hatch-year Long-eared Owl was the first caught at Lucky Peak since 2017. It was incredible to see all three of these unique species side-by-side! Additionally, we had several recaptures of banded Northern Saw-whets this year. We had two recaptures from previous seasons at Lucky Peak, one banded in 2018 and one banded in 2019. We also had a foreign recapture that was banded in 2019 by the Owl Research Institute in western Montana. We love catching owls from previous seasons; knowing that they have made it successfully through another year and another long migration journey!

This article is part of our 2020 end of the year newsletter! View the full newsletter here, or click “older posts” below to read the next article.

Make sure you don’t miss out! Sign up to get our annual email update.