By Teague Scott

We’ve known we were lucky to be graced by the presence of these unique scavengers since we began studying vultures in Gorongosa National Park. Firstly, they are gorgeous. The rest of the avian scavenging world officially has its charismatic figurehead. Secondly, they are the only African vulture that exhibits sexual dimorphism (morphological differences between males and females) in both plumage and size. This is an interesting phenomenon that we see in numerous other raptor species – perhaps you’re familiar with Accipiters exhibiting size dimorphism and Northern Harriers plumage dimorphism? There are numerous hypotheses for these differences that we won’t dig into here, but there are many interesting papers on the subject!

Thirdly, the White-headed Vulture has been observed hunting… I know you’re thinking, “no way, a vulture! hunting!” but yes, I’m serious! One of our collaborators, Cambell Murn, from the Hawk Conservancy Trust in the UK, has observed White-headed Vultures hunting small mammals and reptiles with his own two eyes. Lastly, the White-headed is arguably the rarest of Africa’s vultures. It is seldom seen outside of protected areas (National Parks, game reserves, etc.), and is often found in low densities in even the most suitable habitat.

This last point has held for decades. Researchers have long pondered the reasons for why the White-headed Vulture is so elusive, but no one has figured it out. Answering questions such as these are difficult when your study species is hard to find. Seven-foot wingspans capable of soaring great distances in a relatively short amount of time don’t help the matter; one minute you’re making observations, the next, your bird is kilometers away!

On top of this, White-headed populations are on a downward trajectory paralleling that of many other vulture species in Africa.

In 2017, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) revised its conservation status from vulnerable to critically endangered – a scary jump. One estimate places the global population at around 5,500 birds. So, we are officially runners in a race to learn more about these birds and help to guide conservation decisions before the opportunity is lost.

This last point is also where Gorongosa National Park stands out. We believe that the park not only contains important habitat for White-headed Vultures, but that it hosts the greatest density of this species in the world! Go on a game-drive (aka safari) in the park, and one is almost guaranteed to see one of these birds. This can’t be said for many other protected areas in Africa.

If you’re lucky enough to find vultures attending a carcass, you’ll probably see a White-headed in the mix. If you’re really lucky, you’ll see two, three, or even four. We’ve seen six of these birds surrounding a carcass at the same time – a truly amazing congregation by anyone’s standards! For this reason, we’ve been lucky to trap and tag 12 White-headed Vultures with satellite transmitters. This is an unprecedented sample size, and movement data allow for new insights into the biology of this hard to study species.

We’re in the thick of analyzing these movement data now and are making some interesting discoveries.

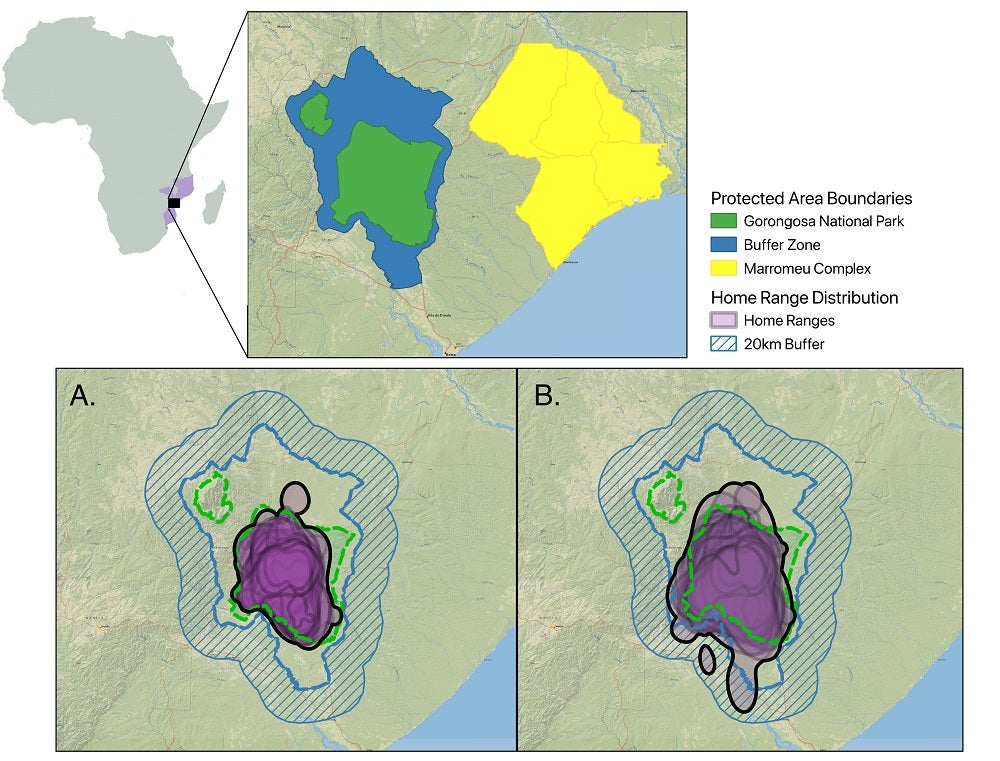

Our first research questions revolve around an analysis of home range. We can loosely define this concept as, “the area required by an individual to carry out basic biological processes.” We’ve found an average monthly home range size of almost 1400 km2. This sounds huge, but keep in mind, these are birds capable of moving large distances with little effort. It is also important to keep in mind Gorongosa National Park is 3700 km2. In any given month, the majority of our birds aren’t ranging over every square kilometer the park has to offer. This is evident when one visualizes these 129 monthly home ranges.

While a few of the birds make the occasional trip outside the park boundaries, most don’t leave the park’s buffer zone (the area incorporated into the park’s recovery effort to ensure that communities flourish AND exist in harmony with wildlife within the park). Exactly 92 of these 129 monthly home ranges fall entirely within the park’s buffer zone – that’s more than 70%. This figure jumps to greater than 90% if we look within a 20km distance outside of the park buffer zone. This pattern is so pronounced that many of these monthly home ranges are effectively shaped by lines that we can only see definitively on a map. Isn’t it crazy that political boundaries can so effectively constrain a species’ distribution?

These birds need something that Gorongosa has. This something remains to be understood but could be the key to ensuring that the species persists and perhaps even returns to vacated parts of its historic distribution. We are excited to be studying these majestic birds, building on current knowledge, and guiding conservation and research decisions going forward.

This article is part of our 2019 end of the year newsletter! View the full newsletter here, or click “older posts” below to read the next article.