Organic versus conventional foods: are they really better for people’s health? Are all organic foods created equal, and if not, which do we pick and why do we pick them? These seemingly simple questions are fraught with a barrage of personal and political beliefs and values. Yet the voice of reason that is often missing from the conversation is science. One reason for this knowledge gap is that studies involving dietary intervention (i.e., replacing conventionally produced foods with organic foods) usually are only conducted for one- to two-week periods on small populations. This period of time isn’t long enough to provide conclusive evidence that a test group became healthier on an organic diet.

That’s why Cynthia Curl, an assistant professor in Boise State’s Department of Community and Environmental Health, has conducted what is believed to be the first ever long-term diet intervention study on the effects of organic produce on pregnant women. Results of the Treasure Valley study revealed that adding organic produce to an individual’s diet, as compared to conventional produce, significantly reduced exposure to pyrethroid insecticides – that is, insecticides that are neurotoxic to insects as well as humans in large enough doses.

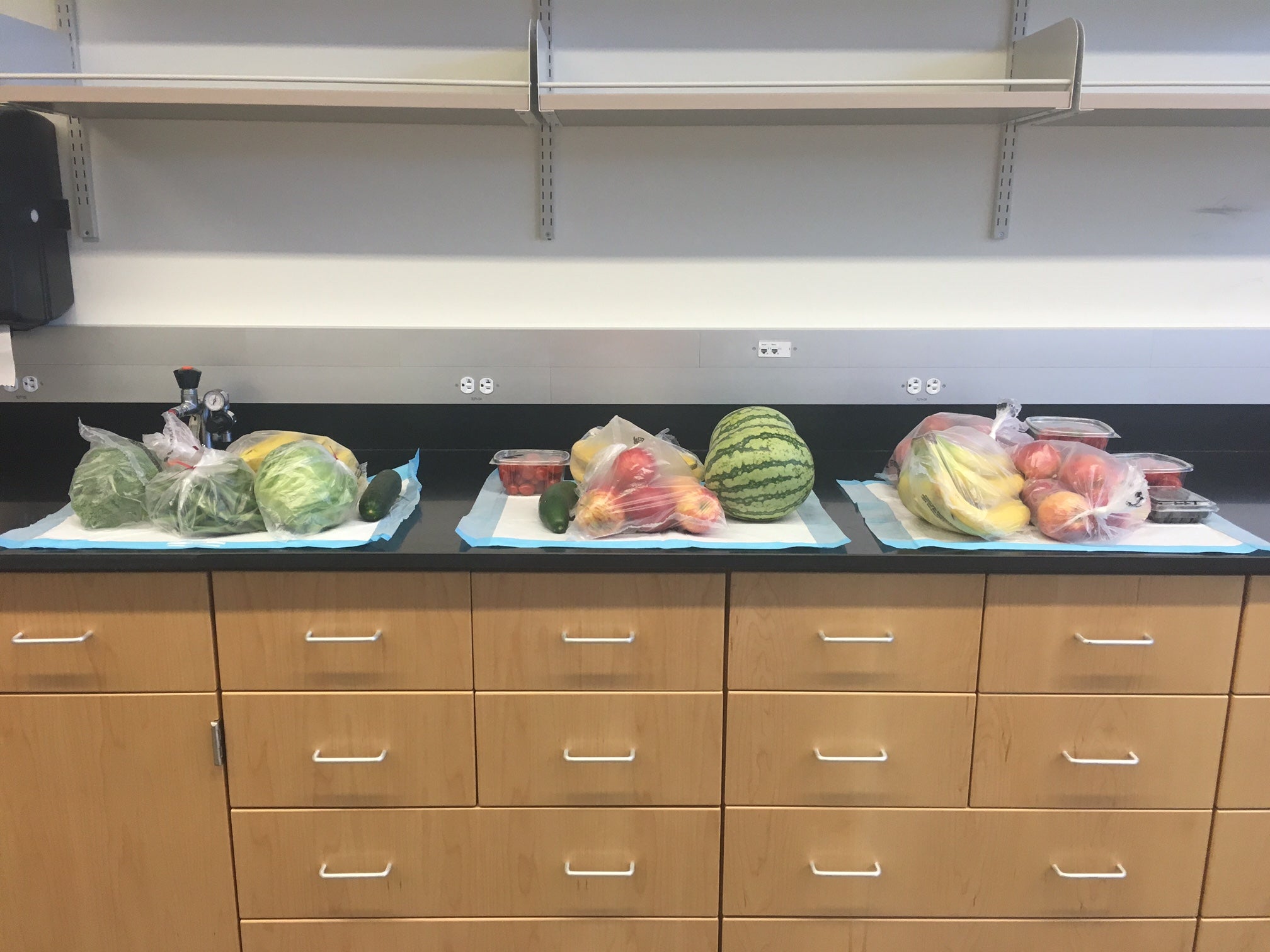

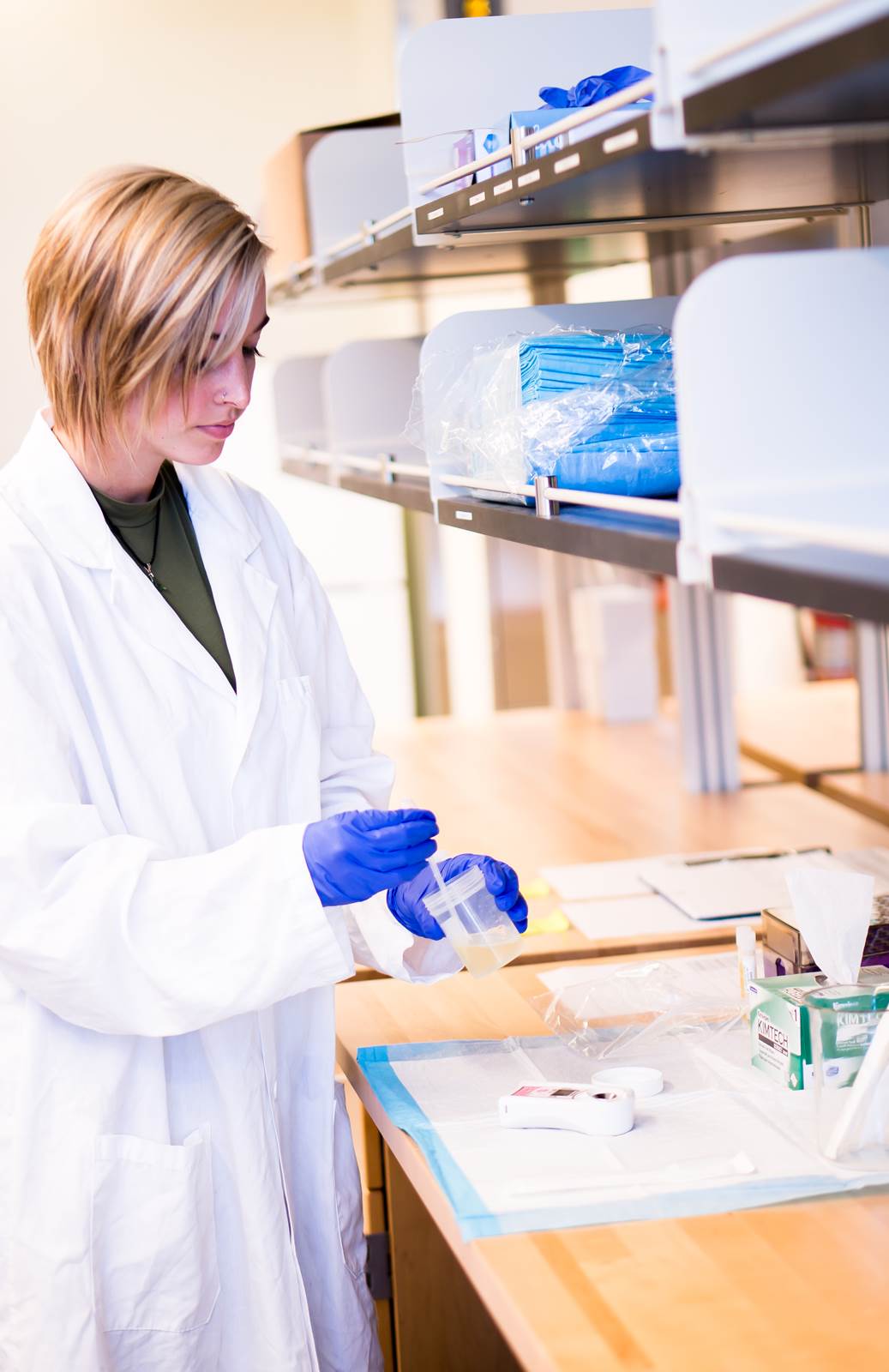

For six months, spanning 20 women’s second and third trimesters, Curl’s two study groups were provided with weekly deliveries of fresh fruits and vegetables. One group was given organic produce while the other received conventional produce. Weekly urine samples were collected from both groups and analyzed by the Center for Disease Control. The results showed that women consuming organic produce had significantly lower pesticide metabolites.

“This research is novel because it’s also the first study done in pregnant women, and there’s a lot of research showing that time in-utero is a sensitive time for development,” said Curl. “So if we were to look for a health effect from decreasing pesticide exposure, one of the places we might see it — if it exists — is in this population.”

This study also proves the feasibility of conducting long-term organic diet intervention study among pregnant women. Curl believes that by following this study’s parameters with a much larger test group, and then monitoring the health and development of the children after birth, it would be possible to conclusively answer the question of whether there is a measurable health benefit to children if their mothers consume organic, rather than conventional, food during pregnancy.

“In order to look at the kind of health effects that we might be interested in, which would be neurological effects in the kids — like incidents of [attention deficit disorder], changes in memory and IQ, things that we have seen in agricultural populations — we would need to have a sample size of maybe 500 pregnant women,” Curl said.

This study also demonstrates that it is not necessary to consume a fully organic diet in order to experience a significant change in pesticide exposure. By supplementing participants’ diets with organic fruits and vegetables, the authors better imitated how many people actually consume organic food – as a part of their diet rather than the whole.

As the need to produce enough food for our growing global population escalates, so too has the urgency of the organic versus conventional foods debate. The higher costs of producing and buying organic produce, evolving agricultural practices, the effects of pesticides on the environment, the burgeoning $40 billion organic food industry: all of these elements, and many more, complicate and muddy an issue that still suffers from a lack of scientific understanding.

Yet Curl asserted that organic or not, the proven health benefits of eating fruits and vegetables far outweighs any concerns about potential negative effects of pesticide exposure.

“Even as we learn more about the pesticide exposure that we might be getting from our diets, it’s important to put that in the right context and understand that the first order is to eat as many fruits and vegetables as possible,” said Curl. “If there are pesticides that are in our food supply at levels that would lead to negative health effects, the answer then is to introduce legislation that would reduce those levels in everyone’s food supply, not necessarily to simply encourage those who can buy organic to buy organic.”

Curl’s research was supported by a team of Boise State undergraduates, including: Jessica Porter, Ian Penwell, Rachel Phinney, Justin Nelson, Hope Murray, Jonathan Wheatley Makaela Bournazian, Dana Kerins and Abigail Thomas. The team also partnered with the Central District Health Department’s Women, Infants and Children program for participant recruitment; Grasmick Produce and Idaho’s Bounty for the produce; Wild Safari Deliveries to deliver the food; and Boise State’s Office of Information Technology for the novel development of tailored food diary apps.

Curl’s research findings were published on July 16 in the peer-reviewed journal Environment International in an article titled “Effect of a 24-week randomized trial of an organic produce intervention on pyrethroid and organophosphate pesticide exposure among pregnant women.

View Curl’s research in its entirety.

Research reported in this publication was supported by Grant UL1 TR002319 from the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (CTSA) and by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01ES028745. The food for this study was purchased through a Boise State Pony Up Crowdfunding campaign.

-By Brianne Phillips