The sounds of engines greeted the crowd as they gathered last Saturday night for the NAPA Auto Parts Idaho 208 K&N race at Meridian Speedway. Television cameras broadcast across the nation as pit crews escorted brightly colored vehicles onto the track. Boise State’s Stafford Smith (car #30) was cheered on by Broncos of all ages wearing the orange and blue. Each race brought its own excitement and eventual thrilling conclusion. Winners were applauded, runners up vowed to do better, and the survivor of the occasional wreck shook their head and evaluated the work before them to get back into the game. This is the thrill of racing.

Hailing from Meridian, Stafford and his father started go-karting as a winter activity at the age of 12. It snowballed into competitive karting around the northwest and British Columbia, and now cars. Stafford found he enjoyed it, winning numerous trophies and even a national championship. By the time he was 17 he found himself behind the wheel of a NASCAR vehicle competing against racers across the country. Working in the team shop on various vehicles, the mechanical engineering sophomore trades maintenance and repair work for driving time.

Along the way, his dad found himself immersed in the business side of racing. “I would rather tighten and loosen some bolts than deal with some of the paperwork and stuff that (dad) does.”

So what drives Stafford towards engineering? “I’ve always taken stuff apart and put it back together, so it would be cool to design my own stuff to take apart and put back together. And the issues I’ve seen in the field, in the racing cars and stuff, is inherently not quite as good as it could be. I’d like to be a part of designing and refining so that in the future all of it’s easier to work on.”

Math comes easy for Stafford. “It’s just another language, you know what I mean?” He pursues an in-depth meaning for things; not just “do this,” but why it happens. He loves how integrals actually work, and how they can be applied. “We used to take data off go-karts and get acceleration versus time graphs,” he recalls. “It’s been really cool to see those same graphs in a math classroom and try and figure out what they actually meant.”

Racing and school have been a good balance for each other. “Being able to feel the physics in the race car has helped in the classroom,” he says. “It’s been a little bit of a two-way street there, because when someone talks about physics, I’ve been there and I’ve seen the graph because I’ve made the graph for something I’ve done, so I understand where it comes from.”

His desire to find better ways to do things motivates him in the shop and in his academic goals. “I’d like to apply everything I’ve learned as soon as possible,” he says, but doesn’t discount the idea of pursuing a Masters or even a PhD.

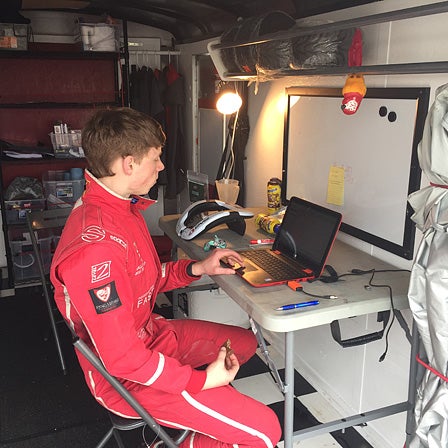

He enjoys getting into what he works on. Last summer he traveled the country to a variety of racing venues. “I’m in the truck,” he explains. “A lot of the drivers will fly in and the car will be there. But I get to do the whole prep, drive, get there, unload, drive the car, load the car back up, and drive back home.” He likes getting his hands dirty. “Very, very dirty.”

And very busy, too. His racing schedule overlaps school, with races extending into October and beginning again in April. “If I can, I’d love to go back East to where the bigger teams are, and just see how a big team functions. It’s not just the engineers; it’s the business side of it. All the data that comes in off the cars that they have time to look at instead of us,” he notes. “We’re fixing things and getting it ready to go again, which is good for problem solving because you gotta get it done, but I’d really like to learn the more mathematically challenging parts of racing.”

Stafford sees himself moving ahead in professional racing. “If I can’t drive the cars, I’d like to be working on some sort of car. They’re all leading edge in what they get to engineer. The big teams will spend near three-quarters of a million dollars a year, and we’re nowhere near that here. We don’t have the staff. We don’t have that, so every time we’re fighting uphill. It’s really satisfying when you can be within tenths of seconds, because their cost for one more tenth is $30,000, and if you put that in perspective, it’s probably worth it just to do what we do and work and learn as much as we can so we can move on.”

Students interested in racing have a great local opportunity. “We’re building a kart track out by Firebird Raceway,” says Stafford. “I’d love to see students with karts, because they’re just really simple cars. You don’t have to worry about suspension, but the forces are all still there, and the data tracking and acquisition is all still there, so you can read graphs and see what’s going on. You can improve the kart, because it’s not like we’re gonna run a national series, so the rules will be lax. You can change things, experiment with things.”

Two more races to go this year, but Stafford is eager to get involved in his lab classes. Time will soon be hear when the roar of the engines will call him to a new season on the track.