“It’s hard to put light through a rock,” Matt Kohn states plainly, “you have to grind it really thin so that light passes through it.” But why would someone want to push light through a rock?

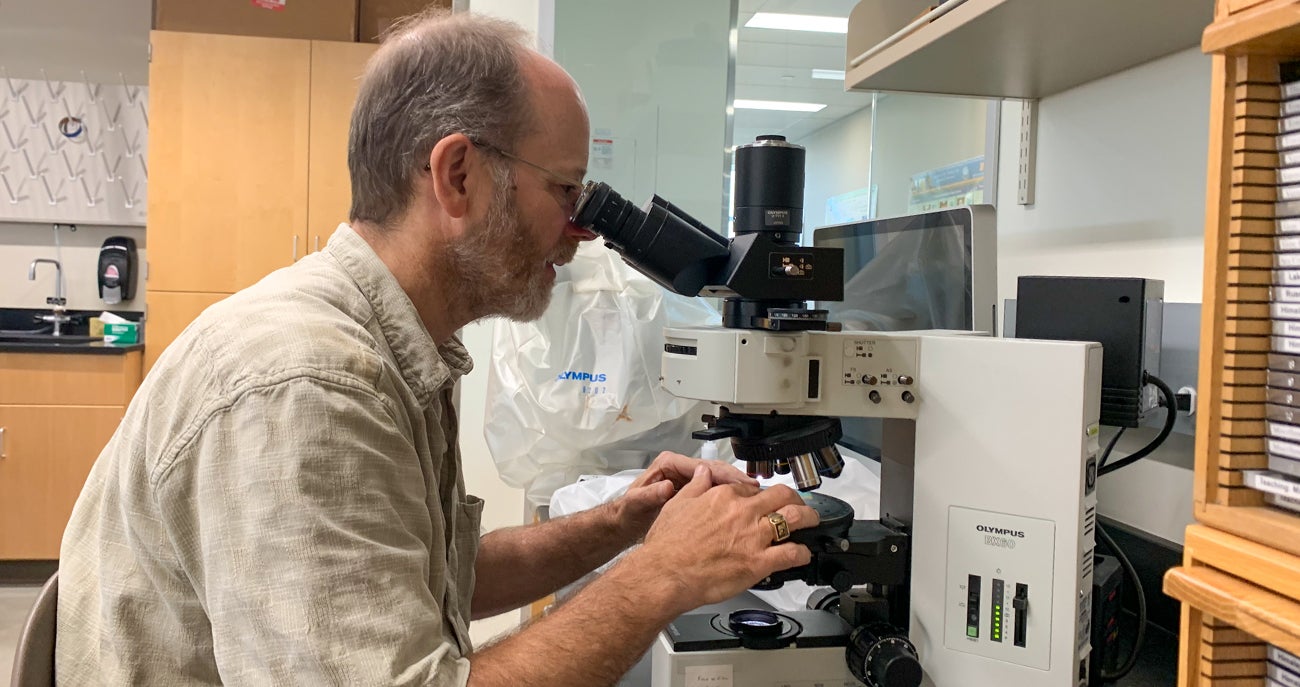

Along with his National Science Foundation-funded research projects, Kohn, a distinguished professor in the Department of Geosciences at Boise State, also teaches upper-division courses in optical mineralogy. He explains that these courses introduce students to the technical jargon and scientific methodologies utilized to identify minerals—how to grind rocks to 30/1000th of a millimeter (thinner than a human hair) and affix these to slides for observation using a petrographic microscope. “It’s a marketable skill that we work hard to train our students how to do,” he said.

In February of 2021, he realized that many of his students couldn’t make it into the lab or had concerns relating to COVID, “So I just made little videos of all the rocks we were looking at in class.” Kohn created the videos using the petrographic microscope which literally pushes light through the rock and allows geologists to filter the light using two polarizing filters. Polarized light waves pass through minerals in a particular direction and the videos demonstrate to students how each mineral produces a certain wavelength of light, or color, based on the filters and rotation. Students learn to identify the mineral content as well as determine the conditions that formed the rock.

But a comment on one of the videos Kohn uploaded changed everything. A student, most likely from Taiwan based on analytics, asked, “Could you please make instructional videos so that I can learn how to identify these minerals?” The student went on to explain that they had little access to a petrographic microscope and no instructors to teach how to use it properly. While Kohn’s videos worked well as a demonstration tool for his lab classes, these did not instruct students outside of his classroom on how to use the microscope and identify minerals.

“It really stuck with me because I want to help people like this,” Kohn said. So in March of 2021 he started creating instructional videos designed to assist any student with an upper-division background in geology on how to use the microscope to identify particular minerals.

In August of 2022, Kohn’s YouTube channel passed 100,000 video views. “I have to say that it’s a little hard to know why somebody will click on a YouTube video,” Kohn said. While YouTube analytics do not explain exactly from where people view the videos, Kohn suspects that many are like the student from Taiwan who are technically savvy but who simply do not have easy access to this equipment, “or it could be they really want another explanation.”

Many of the views originate from India and Kohn explains that does not surprise him, “partly because they have over a billion people and that alone makes a difference.” Since people in China do not have access to YouTube, Kohn also uploads the instructional videos to a video-streaming website in China. “I can’t rule out the possibility that some of what I’m doing is teaching students how to speak technically,” he said.

On the Chinese site for example, students can listen to Kohn’s English instructions and view a translation in both English and Chinese based upon the captions he uploads. Along with India and China, many viewers watch from South Africa, Chile and the United States too, “I’m like, ‘great,’ I never could have anticipated that,” he said.

Boise State geology students graduate and go on to further study in graduate school or find careers in environment, mining and hydrology in industry and government regulatory positions. While Kohn said he created the videos specifically for students in mineralogy classes, he states that, “the average person will maybe not get a lot out of this other than the fact that some of these minerals are just beautiful.”