Idaho Democrats recently nominated Paulette Jordan, a two-term state legislator and enrolled member of the Couer d’Alene Tribe, as their candidate for governor. Jordan’s nomination has the potential to make history, as it represents a number of firsts for both the country and the state of Idaho. Never has a Native American led a state as governor. Native Americans are also a very small minority of congressional representatives; currently, only two members of Congress are Native American (both serve Oklahoma). But Jordan represents another first for Idaho—like twenty-one other states, Idaho has never elected a woman governor. Jordan is just one of several women around the country aiming to change that.

As the nation seems potentially poised for significant change, it is worthwhile to ask why has so little progress for women been made at this level of government. Political science scholarship has recently been thinking more about women’s representation in terms of office level variation, and new studies suggest that executive offices like the governor’s seat are even more inaccessible to women than state houses and Congress.

WHERE ARE ALL THE WOMEN GOVERNORS?

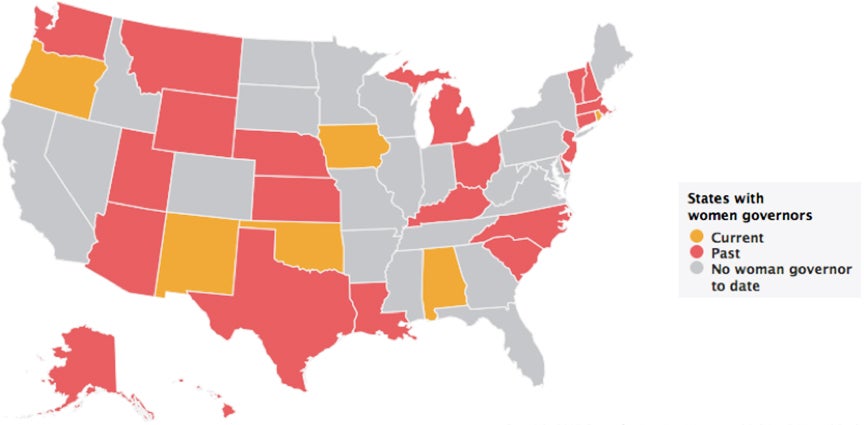

According to the Center for American Women in Politics (CAWP), only 39 women have ever served as governors (22 Democrats and 17 Republican); of those 39, eleven assumed office due to succession, four of whom eventually won on their own terms. The twenty-two states that have yet to elect a woman governor are Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New York, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

WILL WOMEN RUN?

In order for women to be elected, they need to run, and ample scholarship finds that women are just less likely to run for office than men. Why is this the case? First, there is evidence that women are less likely to be recruited or encouraged to run than men, however recent studies find recruitment disparities to be disappearing, at least amongst Democrats. Recruitment bias stems from many factors, but foremost among them is the eligibility pool from where political parties and recruiters identify potential candidates. These pools, like prestigious law firms or business executive suites, are made up of more men than women, therefore more men are typically contacted; where women’s presence in the pipeline is scarce, so too is their political representation.

However, even amongst women who occupy the eligibility pool, women are also less likely to perceive of themselves as qualified than men, also contributing to their underrepresentation. Perception of qualification is an individual’s belief that he or she is qualified to run for political office. Unfortunately, studies find this qualification gap to emerge early in life. In their report, “Girls Just Wanna Not Run,” Jennifer Lawless and Richard Fox find that amongst those in early adulthood, aged 18–25, seventy percent of young men say “yes” or “maybe” in response to whether or not they think they “know enough to run for political office,” compared to just 49 percent of young women. Together, encouragement differences and qualification perception lead to fewer women running.

Yet, as has been widely reported, many more women are willing to run in 2018 for local, state, and federal races. What has changed? And what does this mean for women running for governor?

NO SHORTAGE OF WOMEN IN 2018

According to Emily’s List, the country’s leading interest group directed at recruiting and encouraging women to run for office, around 26,000 women have expressed interest in running since January 2017. Other groups – like Run for Something, She Should Run, and VoteRunLead – also boast big numbers of interested women.

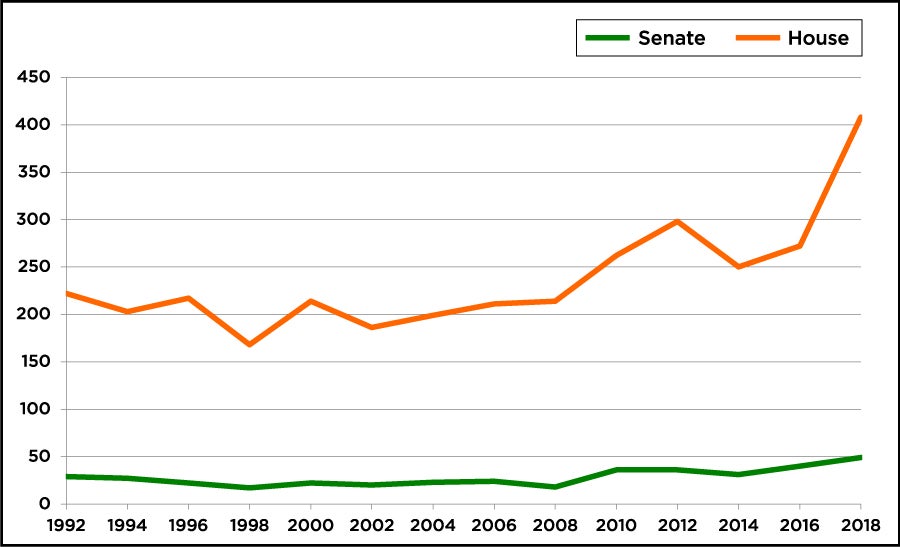

The latest estimates by CAWP have 408 women in the running for their party’s nomination for the U.S. House of Representatives, 49 women for U.S. Senate, and 65 women for Governor. This is a dramatic increase since 2016, when 272 women ran for their party’s nomination for the House, and 40 for Senate, and six women sought the governorship. Following their primary races, just 16 women ran for the Senate, 167 for House seats, and 2 for governor (there were just 12 governors races that year). Once the 2018 primaries have played out, the number of women in the running will inevitably shrink, but the enthusiasm still represents a drastic increase from previous years.

Women Running as Major Party Primary Candidates, 1992-2018

Although more research is needed to identify what has led to the surge in women running for office, it is likely in part explained by Hillary Clinton’s candidacy for president. Although much of the reporting on the wave of women’s interest has focused on women’s response as a backlash to both President Trump’s overt sexism on the campaign trail and the perception of Clinton’s mistreatment by the media, empirical evidence for this reaction is still missing. However, new scholarship at least finds that when women emerge as high profile candidates (like Clinton), other women are mobilized to run. This “role model” effect has been observed in other instances, as well.

However, experts caution against over-estimating women’s success in 2018 because reports find men are running at higher rates as well. Additionally, many women running for Congress are running as challengers, instead of in open seats races. Open seat races are typically more competitive because there is not incumbent to unseat, therefore, experts suggest that many of the women running for Congress will lose their races. Yet women have been successful in primaries where races will be competitive. According to Data for Progress analysis of Daily Kos data, of the 29 primaries in competitive districts that have occurred so far, women have won 15 of them.

But does the same caution for congressional races apply to women running for governor? According to CAWP, women are running for governor in almost every state with a gubernatorial election; there are 36 governors races in 2018, and women are expected to run in 31 of those: Alabama, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Idaho, Kansas, Massachusetts, Maryland, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Nevada, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

So how might women fare in these races?

WOMEN GOVERNORS

Governor races might be a little different than state legislature or congressional seats. While members of Congress and state assemblies are representatives, and viewed as such by their constituents, the title of governor (like president) is more synonymous with power and leadership, two concepts that tend to conflict with notions of femininity and womanhood, with which women are implicitly associated. In their book, Governing Codes, Karrin Vasby Anderson and Kristina Horn Sheeler effectively make this point:

It follows that for women, representing is less a violation of the masculine political culture than leading. After all, (in stereotypical terms, at least) leading requires aggression, initiative, expertise, and reason. Representing requires concern and deference to the public good, connection and concern for humane rather than personal interests.

The empirical evidence for gender stereotype effects on women who run for governor is limited, given the few cases we have to study. However, in her book, When Does Gender Matter, Kathleen Dolan finds gender stereotypes indeed hurt women who run to lead their state.

Beyond implicit gender bias, women running for governor in 2018 face institutionalized hurdles as well. Although more than half (16) of the 31 governors races with women running are open races, even if women secure their party’s nomination, they will likely be running as the challenging party’s nominee. Moreover, many of these races still have their primaries ahead of them, and the field is competitive. For example, in California, Gavin Newsom is his party’s front-runner, well ahead of Delaine Easton. Similarly, Cynthia Nixon is running in the Democratic primary in New York against incumbent Andrew Cuomo.

In sum, while the wave of women running for office in 2018 may not upset the century-long underrepresentation of women in congressional and state executive offices, women’s increased interest in public service suggests that many of the barriers women typically face, like encouragement disparities and their own perception that they lack qualifications, are being eroded. Whether this is due to actual or perceived changes to the political landscape remains under-explored. But as women continue to enter high profile races like those for governor, we will see trickle down role model effects that will have an impact on future races, regardless of the immediate outcome. And this is a win for women.