Dr. Burkhart specializes in research on explanatory factors of cross-national democratization patterns, Canada-US borderlands and environmental policy, and political culture. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Iowa and has been a visiting professor at the Norwegian Technical and National University in Trondheim, Norway. Dr. Burkhart’s book Turmoil in American Public Policy: Science, Democracy, and the Environment, was published by Praeger Press (2010). His research has also been published in several peer-reviewed journals, including American Political Science Review, American Review of Canadian Studies, European Journal of Political Research, Journal of Borderlands Studies, Journal of Politics, Social Science Journal, and Social Science Quarterly.

Note: This article is an update and post-mortem assessment of the election forecasting model published in The Blue Review on April 17, 2017, in advance of the two rounds of the French presidential election. To read that original article, please click here.

While millions were watching the outcome of the French presidential elections to see what the future held for France, Europe, and burgeoning populist movements across the globe, I was paying attention for a different reason: to see how well the forecasting model I had previously published in The Blue Review performed. I originally generated the forecasts by applying two statistical models from the political science literature to data collected on each prior presidential election during the French Fifth Republic (1965-2012). The analytic techniques resulted in vote equations into which I inserted values of the predictor variables corresponding to conditions during the 2017 campaign, creating forecasts of the first round vote on April 23rd and the second round vote on May 7th.

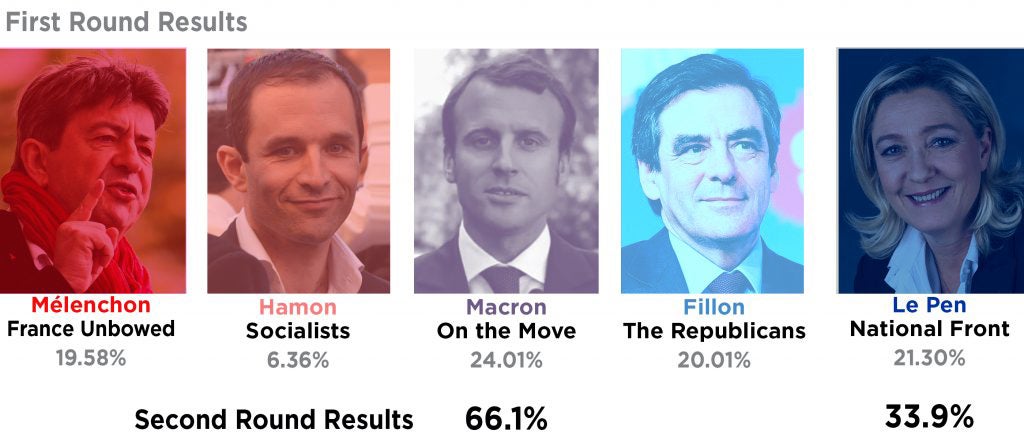

The first round vote was a free-for-all contested between eleven candidates, ranging the ideological spectrum from extreme left Communist (represented by Jean-Luc Mélenchon) to extreme right National Front (represented by Marine Le Pen). The range of percentage votes received was from 0.18% to 24.01%. Since no one received a majority of the first round vote, the top two candidates, Le Pen (21.3%) and centrist Emmanuel Macron (24.01%), contested the second round vote, narrowly beating the more mainstream rightist François Fillon (20.01%) and Mélenchon (19.58%).

The forecast for the first round was based on the popularity of the incumbent president, Socialist François Hollande, last November, with the voters treating the election as a referendum on the government. Recalling that Hollande’s popularity was at a historically low 4%, the forecast for the incumbent government’s candidate, Benoît Hamon, was for 6.86% of the vote on the first round, a wipeout. (So unpopular was Hollande that he did not even attempt to run for re-election.) In fact, Benoît received 6.36% of the vote, vanquishing the Socialists and calling into question the party’s viability in future elections. The model performed well in forecasting that massive first round defeat, overestimating the result by .05%. This election went further in repudiating the established Left and Right parties, as for the first time during the Fifth Republic neither established party made it to the second round.

The second round forecast was based on the high correlation of the vote between the first round result and the second round result in past presidential elections. The correlation was so high that I used it to estimate the second round result as the Right receiving 48.09% of the vote, thus giving Macron the majority of the vote and the Élysée Palace. The actual result for the Right candidate, Le Pen, was 33.94%, well outside even the lowest statistically likely score from the forecasting model, 45.32%, or 11.28% away from the actual result. At minimum, the second round forecast at least predicted the eventual winner, and suggested that the Right, like the Socialist left during the first round, severely underperformed based on past elections. (Of course, there is the perspective that the National Front is so far beyond the traditional Right that it could not ever count on these voters to support Le Pen en massé. I have more to say on this perspective below.)

There were, of course, unique factors in play in 2017 that will confound forecasting, an endeavor that relies on consistent patterns of behavior. The most notable was the anti-establishment flavor of the second round, but there were other unusual features. The abstention rate during the second round was 25.38%, an unsurprisingly high rate during this establishment-shattering election during which voters expressed a particular distain for politicians. An additional 11.49% cast either blank or spoiled ballots, most likely a protest vote, leading to a voter turnout of 74.62%, the lowest turnout since 1969. (For comparison, however, this low turnout is high compared to U.S. presidential elections. The last U.S. election with turnout that high was in 1896.)

The campaigns run by Macron and Le Pen between the first and second rounds are of interest to this rather errant forecast. With the establishment parties rendered asunder in the first round, their voters were up for grabs by Macron and Le Pen. Since Le Pen was an extreme right candidate, she could not automatically count on the support from the right wing of French politics. She did secure the support of Nicolas Dupont-Aignan’s Debout la France moderate right wing nationalist party by announcing that should she win, Dupont-Aignan would become the Prime Minister. (Under the Fifth Republic constitution, the President selects the Prime Minister, who then must be able to command the National Assembly legislature in the passage of legislation.) Debout la France is a small party, though, winning only 4.7% of the first round presidential vote. This capture by Le Pen proved to be insufficient for her winning prospects.

French pollsters tracked closely the voters for the main losing first round candidates as to their second round preferences, continuously polling throughout the two weeks of campaigning. Overwhelmingly, these voters supported Macron during the second round campaign, which included a fiery debate as obstreperous as the Trump-Clinton debates in 2016. For voters supporting Mélenchon in the first round, on average from the eight public opinion firms, 48% supported Macron and 16% supported Le Pen. For voters supporting Hamon, on average 75% supported Macron and 5% supported Le Pen. For voters supporting Fillon, 45% supported Macron and 28% supported Le Pen. Macron clearly capitalized on the freed first round supporters of other candidates. Macron’s centrist political position turned out to be close to the ideal “median voter” first articulated sixty years ago by Anthony Downs in his book An Economic Theory of Democracy, which postulated that politicians who sought to appeal to voters in the middle of the ideological spectrum had the greatest potential to win a broader array of voters than those who sought voters at the extremes. Macron was able to peel voters away from Le Pen by performing this Downsian maneuver.

From an election forecasting perspective, French polling was very accurate during this campaign, which made the predictive model relatively accurate as well on the first round. The second round forecast, relying on the predictable return of voters to either the Left or Right main candidates, suffered from the lack of normalcy of the final candidates. Unhinged from their traditional ideological moorings, the French voting calculus could not be as well forecasted as before, though the broad tendency toward the winner could be detected from this forecasting formula. Even in this unusual election, a bedrock indicator such as governmental performance sustained itself as a forecasting instrument that could point to the winning candidate. Still, it is hard to overestimate just how transformative this election was for French politics. In short, L’électeur français continuera à naviguer dans les eaux inexplorées.