Markus B. Siewert is currently an academic researcher at the Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany, and visiting fellow at the Center for the Study of Political Change at the University of Siena, Italy. His substantial research interests include American politics focusing on the US presidency, as well as diverse aspects of the qualities of established democracies in comparative perspective.

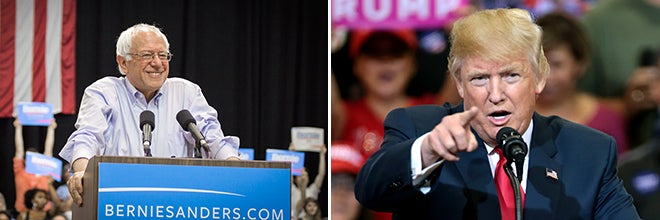

No matter where in the world we turn our eyes, populist actors and ideas seem to be on the march. While populist figureheads from across the ideological spectrum have been a decisive phenomenon in Latin America and Asia for the last decades, populism is currently celebrating an impressive renaissance also in Europe and the United States. For months, people were holding their breath while watching Austria, the Netherlands, and France, wondering whether populists like Hofer, Wilders, or Le Pen would manage to win their elections – a circumstance which following the shockwave the UK send via the Brexit vote would have likely sealed the fate of the European Union. The presidential primaries in the US had already heralded the dawn of a profound change in politics with the rise of Bernie Sanders and Donald J. Trump as standard-bearers of populist movements on the left and the right, a groundswell that brought the latter of the two into the White House. There is no doubt about it: the specter of populism is now haunting representative democracies!

WHAT IS POPULISM?

The notion of populism is widely contested. This has first something to do with the fact that populism has traveled through time and space developing so many faces that it has become hard to pin it down. Second, the label populist is widely used in the realm of politics as either a battle cry to denounce the political opponent or as a badge of honor reflecting common cause with the masses. It thus carries a heavy normative meaning, since one person’s advocate of the people is in the eyes of another nothing more than a demagogue. Nevertheless, a consensus is emerging in the comparative study of populism; according to Cas Mudde and Cristobal Rovira Kaltwasser, populism is best conceived as “a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic camps, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite,” and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.”

This characterization emphasizes key elements of populism. Making constant reference to the people and claiming to speak for them hardly qualifies as populism. After all, have you ever met a politician who did not claim to represent you and your interest? The heart of the populist message is rather that they, and only they, are the real champion of the people campaigning for their rights and giving them a voice. Moreover, populists contend that something like the general will of the people exists and that it can be articulated against a crooked and fraudulent establishment which aims to distort the will of the people.

The fact that Trump and Sanders can and have been both labeled populist furthermore points to the thinness of the populist ideology, which per se has no vision about how a society should look like and what kind of state is desirable. For the case of the United States, Eric Oliver and Wendy Rahn’s analysis of the speeches given on the campaign trail during the presidential primaries clearly finds these attributes prevalent in the rhetoric of both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Trump, for instance, made extensive use of this kind of language equating himself with the cause of “we, the people”, singling out a corrupted political caste that was failing the American people. Bernie Sanders’s rhetoric was much the same. Although he had been in Washington, D.C. for decades, Sanders blamed economic elites and Wall Street’s pursuit its interests at the expense of Main Street America. The fact that Trump and Sanders can and have been both labeled populist furthermore points to the thinness of the populist ideology, which per se has no vision about how a society should look like and what kind of state is desirable. Since these principles need to come from outside, populism must be combined with other ideologies that are able to offer such a set of unifying ideas. In this respect, populist actors are largely indifferent and hence can be linked to a broad range of ideological positions, ranging from conservatism, progressivism, and socialism to globalism, nationalism, and nativism.

POPULISM IS NOT A REMEDY TO BUT A SUBVERSION OF REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY

Populism is comparable to the (in)famous wolf in sheep’s clothing. Disguising itself as a corrective to a model of representative democracy that fails to serve its citizens, populist projects across the world pledge to overcome these deficiencies and to implement the true will of the people. Fueled by a radical notion of democracy in which the popular sovereignty of the people is unbounded and unrestricted, populism offers the promise to revitalize and democratize our seemingly fatigued and immobile political and societal systems. It is the people who decide what is best for the people – full stop.

However, populism in practice is not a remedy for contemporary democracies but their very subversion. The reasons are hidden behind the guiding principle that politics should be the general will of the people. Who are ‘the’ people and how can we detect its ‘general’ will? In this respect, populism heavily draws upon an organic understanding of the society as one homogenous people while leaving little room for societal pluralism or individualism. Going even one step further, the amorphous body of people in populist thinking is exalted to a status of moral superiority whereas ‘the others’ – those who are not part of the people – are morally degenerated, corrupted, and hence illegitimate. It remains, however, unclear who gets to decide who belongs to the people and who does not – other than the people themselves.

The same holds for identifying the general will of the people. In today’s societies, it can only mean two things: either the will of the people lays with its majority or it needs to be interpreted by some higher authority and approved by popular acclamation. There are many problems with both procedures. While the former exalts the principle of majoritarian rule, the latter cuts short the political process of deliberation altogether since the consensus does not have to be built with consensus like in pluralistic societies but just needs to be found and then proclaimed. In both scenarios, however, the idea of a fixed volonté générale (or general will of the people) involves an uncompromising claim that does not allow for disagreement or opposing voices. Today’s populists have no problem with the principle of representation since they contend to be the exclusive genuine representatives of the people. However, in doing so they frequently deny the legitimacy to their political opponents. In other words: if I represent the true people and their general will, who do you stand for if not the enemy of the people?

PLURALISM, LIBERALISM, AND REPUBLICANISM AS ANTI-POLES TO POPULISM

Populist impulses and messages draw their strengths from many sources. The apparent and perceived failures of modern representative democracy to live up to its promises constitutes one piece of the puzzle. Deficiencies in the political process are often too evident to be neglected. Also in socio-economic terms, today’s societies are deeply crisis-prone and heavily skewed in favor of a small segment of society. On top of that we are living in times of technological and cultural transformations that are so fundamental and massive we could perhaps compare them to the Industrial Revolution. (That it is a relative crisis in the sense that everybody is better off – in political, socio-economic, and cultural terms – today than at any other point in history, does not make it less real.) Yet, it has hopefully become clear that the way forward offered by populism across the world is in its essence anti-pluralistic, anti-liberal, and anti-republican.

In many aspects, the contemporary populist project constitutes a sharp rebuke to what the Founding Fathers envisaged for the United States: for them it was clear that one cannot repudiate pluralism but needs to embrace it; that a system of strong checks and balances must be in place so that power is dispersed; that representatives and institutions need to derive at responsive decisions, and thus must be to a certain degree isolated from the mood of the people; that the political arena must be embedded in the rule of law, thus guaranteeing the protection of minorities; that the general will of the people does not exist a priori but needs to be formed a posteriori through an open, pluralistic, and competitive process of ideas and arguments.

That we – i.e., the people and the elites (not against each other) – need to put more effort into closing the gap between the democracy that today exists and its ideal is beyond debate. The populist message points the way toward a radical version of democracy that unleashes popular sovereignty. If we were to go down this road, we must first realize that in doing so we bid farewell to the principles of pluralism, liberalism, and republicanism.

Top photo credit: Donald Trump in Reno, Nevada by Darron Birgenheier. Flickr Creative Commons. Image cropped.