Jacqueline Lee earned her Ph.D. in Criminology and Criminal Justice from the University of Maryland College Park; an M.A. in Criminology and Criminal Justice, also from University of Maryland College Park, and a J.D. from the University of Oklahoma. Her research interests include: courts and sentencing, criminal justice policy, integration of social science research with legal research, inequalities in the justice system, and the female experience of violence, offending, and punishment.

Stephen N. Hackler grew up in Riggins, Idaho, and recently graduated from Boise State with his B.S. in Criminal Justice. He is currently working as a paralegal at a Boise law firm and plans to attend law school in the future. He enjoys hunting, fishing, and all manner of sports.

Content Warning: This article contains descriptions of violent crimes.

Death penalty cases have always been a challenging area for courts across the United States. In the last several decades, the United States Supreme Court has limited both the types of offenders and types of crimes that are eligible for capital punishment.

In doing so, the Court assesses whether states are using it more or less often over time and whether any states have passed legislation in support of or against the sanction. If a particular punishment or sanction is obsolete, it can be considered cruel and unusual due to a consensus against the acceptability of the punishment.

Idaho has been sentencing fewer and fewer people to death, and our findings below suggest that these trends support the notion that there is an evolving standard and consensus against capital punishment within the state.

Courts and the Death Penalty

It might surprise readers to learn that the constitutionality of punishments is not fixed, but rather evolves with the times. In fact, the Supreme Court examines whether a punishment is cruel and unusual under the 8th amendment of the U.S. Constitution by looking at the punishment in historical and current context.

The key phrase describing the interpretation of the 8th amendment in these cases is: “The Amendment must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.” Essentially, the Court looks to see how the punishment has been used in the past and present—how often, in how many states, etc. The Court also explores trends in general usage, including whether states have outlawed or increased its use.

Several punishments have been declared unconstitutional using this analysis. For example, the Court determined in Woodson v. North Carolina (1976) that mandatory death sentences were unconstitutional. Though mandatory death sentences were common at the time of the writing of the Constitution, jury decisions and legislation across the country examined in 1976 “point[ed] conclusively to the repudiation of automatic death sentences.”

Interestingly, Idaho was also one of the first states to pass an automatic death penalty law after Furman struck down all death penalty statutes in 1972. Idaho’s automatic-death-penalty statute was subsequently struck down by the Idaho Supreme Court because of Woodson.

Another example? The court has used this analysis to rule it unconstitutional to execute the insane. The case, Ford v. Wainwright, originated in Florida and after assessing other states’ practices, the Court found that no other state in the country would permit such a punishment.

This analysis has also been used to prohibit the execution of those with intellectual disabilities. In Atkins v. Virginia, the Supreme Court found that 18 states enacted provisions exempting intellectually disabled persons from execution and also stated that both the consistency and direction of change, as well as the number of states, were important.

In addition, in Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court deemed the death penalty unconstitutional for minors based partly on the fact that even amongst states with the death penalty, 18 prohibited it for minors. The Court also looks at how often people in a particular group are actually executed, regardless of how often they are sentenced to death, as is clear from Kennedy v. Louisiana (2008), among other cases.

A punishment can also violate the evolving standards because it is hardly ever handed down, even when states technically allow for it. In Graham v. Florida (2010), for instance, the Supreme Court declared it cruel and unusual to sentence juveniles to life in prison for non-murder offenses, even though thirty-eight jurisdictions had the penalty on the books, mostly because so few young defendants actually received the punishment.

These cases demonstrate that evolving standards of decency analysis requires a critical assessment of the historical use of a punishment, as well as its current applications. Next, we move to our analysis of the historical and present-day use of the death penalty in the U.S. and Idaho, which shows a significant decline in its application.

Declines in the Death Penalty across the United States

Across the country, the use of and public support for capital punishment has been declining. Twenty-seven states currently have the death penalty “on the books” as of May 2021. However, as of 2019, there were 11 states that had not used it in more than a decade. This list includes California, which has the highest death row population in the country and where the governor recently imposed a moratorium on the death penalty. And, very recently, Virginia’s governor signed a law abolishing the death penalty in the state, which had carried out the most executions of any state in American history.

Death sentences have been declining dramatically nationwide for a number of years; “states reached modern lows in imposed death sentences,” as only thirty-one and thirty-nine defendants were sentenced to death in 2016 and 2017, respectively. This echoes what has continued in recent years: across the United States, there were 310 death sentences in 1995, 73 in 2014, and only 34 in 2019.

There are many theories on the reason for this decline, though research assessing them is limited. These factors include more resistance to the death penalty among jurors and voters and more willingness among prosecutors to consider alternate sentencing options.

Additional factors include the introduction of life without parole (LWOP) statutes, changes in sentencing laws—specifically, changes required by the Supreme Court that affect the jury’s involvement in the sentencing phase, increases to state funding for capital defense attorneys, and declines in homicide rates. A recent in-depth analysis of nationwide data concluded that of those four factors, the most important predictor of a state’s death sentencing rate declining was states providing increased funding for defense attorneys at death penalty trials.

Survey data shows that public support for capital punishment is also on the decline. The peak of public support was in 1996, when almost three-quarters of the country supported the penalty; a Pew poll from 2015 found that number to be only 56%. A 2020 Gallup poll found that only 54% of respondents believed it to be a “morally acceptable” punishment and a 2019 survey found that 60% of people preferred life in prison over capital punishment.

Historical Use in Idaho

Idaho acquired statehood in 1890—later than many other states. However, it wasted no time in establishing the death penalty. Idaho’s previous status as a populated territory incorporated a rudimentary justice system, including capital punishment; it was introduced in 1864 by the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Idaho.

Idaho’s first three executions occurred on the same day — March 4, 1864, with David Howard, Chris Lowery, and Jim Romaine, all convicted of robbery and murder, being hanged in Nez Perce County. The next execution occurred 4 years later, when Anthony McBride, a 34-year-old soldier, was convicted of murder and executed in Ada County on January 24, 1868. Thirteen more executions were carried out between the years of 1868 and 1901.

Before 1901, counties handled their own (frequently public) executions. However, in 1901 it was decided that Idaho’s executions would be moved to the state prison and would no longer be as open to the public.

Nine people were executed in Idaho between 1901 and 1957, with the last hanging in Idaho occurring in January of 1957, after Raymond Snowden was convicted of rape and murder. Thirty-seven more years would then pass before another execution in Idaho in 1994.

Idaho resumed imposing death sentences in 1973, one year after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down all states’ death penalty laws in Furman v. Georgia (1972), but did not execute anyone again until 1994, almost 20 years after the Supreme Court re-affirmed the use of the death penalty in 1976 in Gregg v. Georgia.

Recent Use in Idaho

As with many other states, the death penalty in Idaho—both sentences and executions—has declined substantially over the last several decades. Though Idaho has not placed any official moratorium on capital punishment nor had any judicial abolition like other western states, data indicate that the use of the sanction is so infrequent as to render it obsolete.

To explore this, we first collected information from 1995-2019[1] on five relevant data points: 1) Homicide rates; 2) Death notices filed by prosecutors (this is an official notice required before the state can seek the death penalty in a case); 3) 1st and 2nd degree murder convictions; 4) Death sentences and 5) Executions.

Our second analysis below focuses only on individuals sentenced to death between 1977-2019. For those 42 individuals and 47 sentences (four individuals[2] were resentenced to death after a successful appeal, and one (Erick Virgil Hall) was sentenced to death in 2 separate cases), we gathered information on 1) year of sentencing and 2) year of execution, if any.

We also collected information on their status if they have not been executed, including whether they 3) are currently on death row; 4); died on death row; 5) were exonerated; 6) either had their death sentence reversed or were re-sentenced to a non-capital punishment.

First, homicide data was collected from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports. From this, we calculated the homicide rate per 100,000 people in Idaho. Second, we obtained information on death notices from 2002-present from the State Appellate Public Defender’s Office. Third, we requested information from the Idaho Supreme Court on all Murder I and Murder II convictions in the state.

Fourth, we obtained information on all death sentences post-Furman from a publicly available document from the Idaho Department of Correction (IDOC) and also from relevant internet searches. Lastly, information on completed executions was gathered from IDOC and other public sites such as the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC).

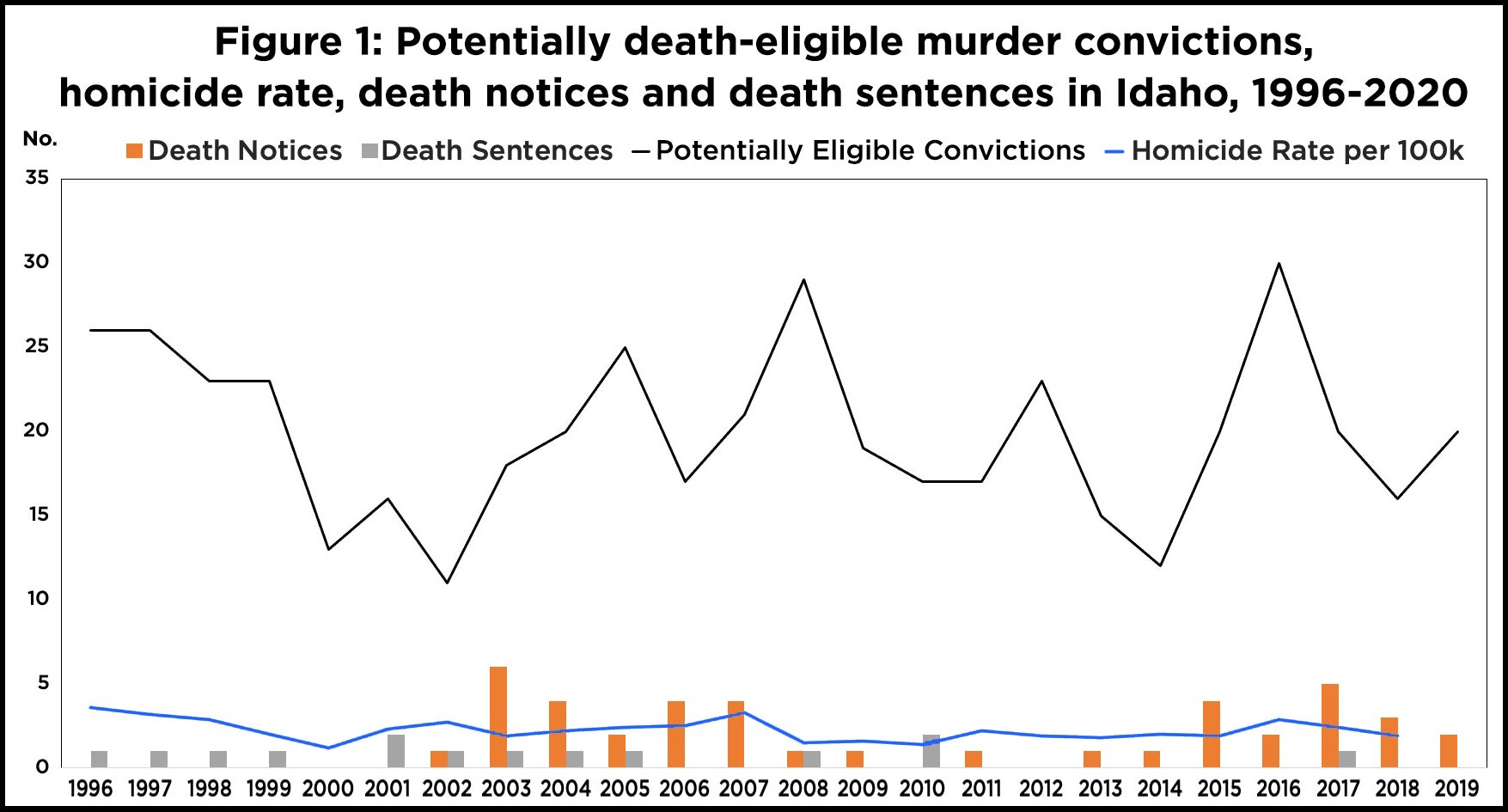

Figure 1 depicts the number of eligible convictions, death notices, death sentences, and homicide rates from 1995-2019. We selected these years for analysis as 1995 was the start of reliable conviction data; unfortunately, we do not have information on death notices prior to 2002. However, we believe this period of time is long enough to reflect the evolving standards of decency, especially given the consistency of the change.

Click here for the data used for Figure 1

The results in Figure 1 reveal many things. First, the number of death-eligible murder convictions (represented by the black line) and overall homicide rate (represented by the blue line) in Idaho are unrelated to the number of death sentences handed down in the state. One can see that the line for eligible convictions varies significantly, but does not lead to any corresponding trend in death sentences.

Second, the three peaks of potentially death-eligible murder convictions in 2005 (25), 2008 (29), and 2016 (30) are not followed by an increase in either death notices (or, as mentioned above) death sentences. This indicates that more murder convictions do not necessarily result in prosecutors even seeking more death sentences, let alone obtaining them.

Third, death sentences have remained quite low over the last several decades in Idaho and despite a high number of potentially eligible murder convictions (173 total between 2011-2019) there has been only 1 death sentence in the last 10 years in Idaho.

Finally, though we did not include the number of executions in Figure 1 in order to make it easier to read, the incredibly small number of executions over two decades is striking. There have been only two executions carried out over this time period: Paul Ezra Rhodes was executed in 2011 (from a 1988 conviction) and Richard Leavitt was executed in 2012 (from a 1985 conviction).

There has been only one other execution in Idaho since 1957; Keith Wells was executed in 1994. He also dropped all of his appeals and effectively asked to be executed; otherwise, he could potentially have attained some judicial relief (a lessened sentence) or been executed much later (or not at all). Even including the Wells case, there have only been three executions in Idaho since 1957, a period of 64 years.

Next, we delved more deeply into the final outcomes of those sentenced to death in Idaho. We use a longer span of cases here because there are more reliable historical records of capital sentences and appeals. Though 42 individuals were sentenced to death between 1977-2019, only three were actually executed, and eight are presently on death row.

Of the remaining individuals, six (Mark Aragon; Zane Fields; Jimmie Thomas; James Wood; Michael Jauhola; Darrell Edward Payne) died of natural causes on death row, 2 (Charles Fain and Donald Paradis) were exonerated, and approximately half—23—ended up with a lighter punishment after their death sentences were reduced on appeal.

Case Studies

There is often an argument made that the “punishment should fit the crime.” This is frequently discussed in especially heinous cases, where the act committed is so despicable that many see the only appropriate recourse as death. Unfortunately, this standard appears to be unevenly applied, with certain horrific crimes not resulting in death notices by the state, while other, less disturbing, cases are pursued as capital cases.

As a result, it seems that the decline in death sentences is not necessarily a function of how aggravated the crimes are, but rather potentially a decline in support for capital punishment reflecting a change in the evolving standard of decency in Idaho.

A good example of this unpredictability can be found in the case of Daniel Ehrlick. In 2009, then 36-year-old Daniel Ehrlick was living with his girlfriend, Melissa Jenkins, her infant son, and Robert Manwill, her 10-year-old son.

On July 24th at around 10 p.m., Ehrlick called 911 and reported Robert missing. Over the next nine days, law enforcement officers and community members organized a massive search that eventually resulted in the discovery of Robert’s body in the New York canal near Kuna on August 3rd, 2009. A forensic pathologist found that the cause of death was either due to severe abdominal trauma, or severe trauma to the skull.

Ehrlick was charged with first degree murder by torture and commission of aggravated battery. At no point did the prosecution publicly state that they would seek the death penalty, despite the fact that the Police Deputy Chief stated that “no other case in Boise history had touched so many people,” and Judge Darla Williamson declared that it was “one of the most difficult” cases she had seen as a trial judge. Ehrlick was sentenced to life in prison, where he is currently incarcerated.

Other cases more directly show how Idahoans have moved away from capital punishment. An example of a jury rejecting the death penalty can be seen in the case of Jason McDermott, who was the leader of a gang known as La Familia in Ada County. Zachariah Street was an 18-year-old-man wishing to join the La Familia gang; during a burglary he hoped would gain him entry into the gang, he was caught by law enforcement.

After his apprehension, Street shared names of other La Familia members with the police, and as a result, McDermott wanted him to be beat up or killed. In the early morning on May 2, 2003, McDermott and two other members of La Familia drove Street out into the desert. After asking Street multiple times if he was afraid, McDermott pulled the trigger and shot Street multiple times; some reports indicate that McDermott and others laughed and hugged afterwards.

McDermott was charged and convicted with first degree murder for the execution-style killing. When McDermott’s case went to trial, the state submitted a notice of intent to seek the death penalty. However, the jury could not unanimously agree on the aggravating circumstances required for institution of capital punishment, and as a result, sentencing was relegated to Judge Cheri Copsey.

Due to a law passed earlier in 2003 that brought Idaho in compliance with a recent Supreme Court case, unless the right to a jury is waived by the defendant, only juries are allowed to mete out death sentences. This meant that Judge Copsey was unable to sentence McDermott to death; he was sentenced to life in prison, where he remains today. Despite the extreme severity of this crime and its heinous nature, a jury still could not reach a definite ruling on capital punishment.

Conclusion

Taken together, both numeric and case study data on the imposition of the death penalty in Idaho support the idea that it is no longer an accepted punishment. The U.S. Supreme Court has already established that in making this assessment, recent use—and historical trends—must be examined. Analysis of Idaho’s use of the death penalty over the last several decades indicates that there is a growing reduction in its use and that this direction of change is consistent and clear.

None of this is meant to say that there are not terrible crimes and murders committed in this state and that the individuals committing them do not deserve to be punished. Life without parole is a viable sentencing option in Idaho and based off of the recent trends of capital punishment in the state, it may be viewed as the most appropriate and severe punishment option for the most heinous offenses.

[1] It would have been ideal to collect information on each of these five data points for the entire post-Furman period. However, there are significant data reliability issues for some of these. However, higher-quality data is available only for those sentenced to death, so we were able to include a longer period of time for our second set of analyses.

[2] Thomas Creech, Timothy Dunlap, Michael Jauhola, and Darrel Edward Payne