Chase Johnson is a Research Associate at Boise State University’s Frank Church Institute. He researches Russian Affairs in addition to assisting the research of the Frank Church Chair of Public Affairs. Chase has degrees in International Relations from Boise State and Johns Hopkins Universities. He served in the U.S. Peace Corps in the Republic of Georgia, and later returned as a researcher at Tbilisi State University. He also served briefly in economic affairs at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow and worked on NATO Affairs for the Defense Department.

To say “the sky is blue” is to state the obvious. People who do so are not adding anything to the conversation about the world around them. They are using their time and effort to state something that is crushingly obvious to any objective observer. This is the challenge for Russia scholars when analyzing the current state of the country’s politics. The discipline’s sky is blue thesis is that Vladimir Putin is the most relevant political force in the country and will be for the foreseeable future. The Russian sky remained blue through this weekend’s presidential election.

Russian voters have spoken, resoundingly affirming Vladimir Putin’s ambition to serve a fourth term. He will now be president until 2024, and potentially longer if any changes are made to the constitution in the next six years. The result was no surprise, but even an objective and independent voter might have chosen Putin after seeing the spectacle of his opponents’ campaigns, punctuated with a sloppy TV debate complete with profanity, sexism, and one upended glass of water.

In reality, Putin was the only candidate. In the election preview I previously published in The Blue Review, I agreed with the consensus of Russia scholars that this election was merely political theater – not an exercise in democracy, but simply playing one on TV. Lacking a political opponent, the greatest threat to Putin’s mandate in this vote was apathy and cynicism. His image was thus contingent on meeting his stated 70-70 goal: 70% of the vote with 70% turnout. To achieve this goal, political groups aired TV spots that hinted at a dystopian future where middle aged men get drafted and each family had a live-in gay man.

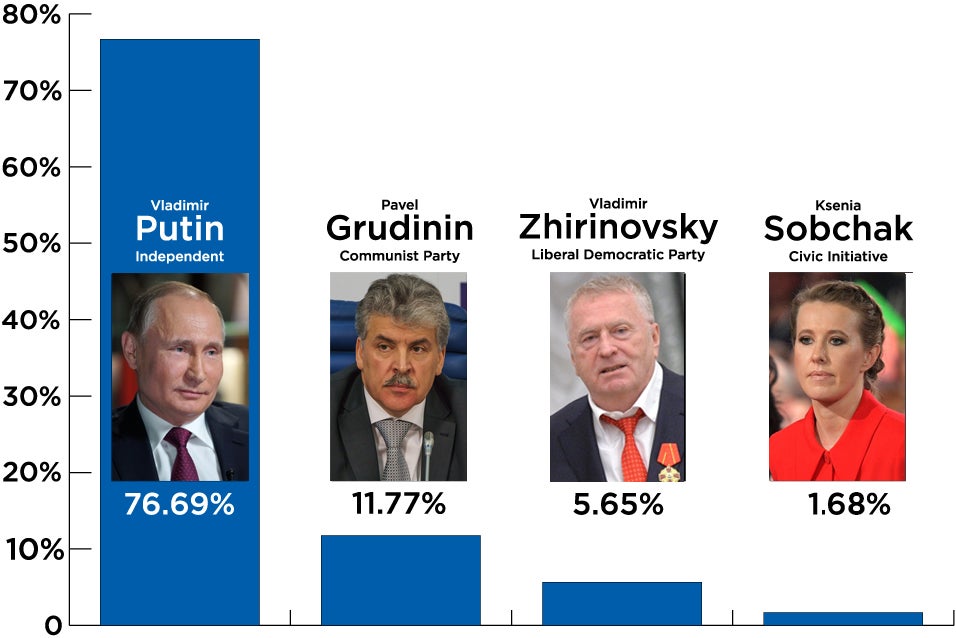

With the vote in, Putin fell just short: 76.7% of the vote, but only 67.5% turnout (the lowest number of any of his victories), yet he does not seem to be fazed. On the first day after the vote, Putin pivoted away from his hardline campaign rhetoric and articulated an ambitious agenda for defense reform and better relations with the West, although these two issues could fall on a wide spectrum of outcomes, and Westerns observers should not expect a noticeable change in rhetoric from the Kremlin.

Why then should observers in the West even care about an election result? We should care because It is a critical waypoint in Putin’s tenure and offers a window into the way he wields his political power across the country, as well as what is done at the local level to curry favor in a world of personality-driven politics and relationship-based graft.

Results of 2018 Russian Presidential Election

WHO WILL RID ME OF THIS TROUBLESOME PRIEST? LOCAL ADMINISTRATORS, THAT’S WHO

Ironically, Vladimir Putin is overwhelmingly popular in Russia. Even peer-reviewed Western-sourced polling efforts have shown that his approval rating is the highest among G-20 heads of state.As with every Russian election since independence, there were widespread reports of fraud: stuffing ballots, distracting monitors, and blocking cameras when counting ballots. However, this was not necessary to guarantee a Putin victory. Ironically, Vladimir Putin is overwhelmingly popular in Russia. Even peer-reviewed Western-sourced polling efforts have shown that his approval rating is the highest among G-20 heads of state. As a result, it is not unreasonable to assume that Putin would have won a decisive victory in a completely free and fair election. Why then do the ballot-boxes get stuffed? It is highly unlikely that Putin and pulls the levers on election manipulation, rather it is done for sycophantic reasons at the local level. Much like King Henry II inadvertently condemned a priest to death by loathing about him to court, local administrators likely interpreted the 70-70 notion as a directive, and not just an aspiration. Furthermore, they do not want to be the region that didn’t meet the 70-70 goal. It would look bad on their record, and they might not be able to call in favors when capturing the next round of Russian pork-barrel spending.

That’s why it is interesting to examine the variation in support for Putin across Russia. The six regions where he received 90% or higher of the vote totals are all either in Crimea (voting for the Russian president for the first time since their annexation in 2014) or the North Caucasus (save for Tuva, a majority minority republic in Southern Siberia). The North Caucasian regions all posted top vote percentages for Putin in his previous election in 2012. These regions are rife with reports of egregious human rights violations. Chechnya, once the target of Russian military intervention, now votes more loyally than almost any other region. Putin also received 94.1% of the vote in Georgia’s breakaway Republic of Abkhazia – a place that is not internationally recognized as part of Russia’s sovereign territory.

The regions with the lowest vote totals were also no surprise. Rounding out the bottom of the list were places like the Jewish autonomous oblast and the Sakha Republic in Yakutia – a place at the forefront of Russia’s economic stagnation, the ills of climate change, and all-but forgotten by the Western elites in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Sakha is likely the epicenter of political apathy if the vote-totals are in any way proscriptive of local-level politics in Russia. These regions, specifically those that do not have an oil and gas industry have been left behind in Russia’s decade of growth in the 2000s – the period when Putin cemented his reputation of stability and wealth. Income inequality is widespread in Russia and those who were left behind are those who today do not believe in the Putin mythos when they cast their votes.

PUTIN SURE LOOKS LIKE BREZHNEV-INCARNATE

One joke about the Soviet Union that any Russia scholar is bound to hear from a local when they travel to the region is the time when Stalin, Khrushchev, and Brezhnev were all on a train when it broke down. When asked what to do, Stalin suggests shooting the crew to motivate them. Khrushchev’s plan is to tell them that communism is waiting at the next stop. Brezhnev does not posit any solution – rather he closes all the windows in the cabin and says, “Just pretend the train is moving!” Such is Putin’s approach to administering Russia since 2014.

In most other states, if a president had the same stewardship of the economy as Putin, they would likely lose re-election. One major reason why Putin was able to consolidate power so effectively in the 2000s was his ability to leverage resource wealth with high energy prices to right the Russian shape after its wild ride through the chaotic 90s. This economic boom has since ended, and the Russian economy looks more and more like the stagnant one under Brezhnev. Since the financial crisis of 2014, which was rooted in low oil prices and exacerbated by Western sanctions, wages have stagnated. Furthermore, Putin has done little to diversify the Russian economy, and perhaps most tellingly, the country’s reserve fund just went bankrupt.

RUSSIA IS UNDEMOCRATIC, BUT IT COULD BE WORSE

Russian voters went to the polls to answer a question which, in the post-truth reality of 2018, is not a foregone conclusion: Is the sky blue? The paradox that Western policymakers must understand is that Vladimir Putin is a threat to worldwide stability, but his absence would be an even greater danger. Furthermore, Russia’s talent pool for president consists of one person. Champions of Western Liberalism can long for a day where Russia may have a legitimate voting franchise with real choice, but given the current state of Russian politics, this could potentially be a much greater threat than another six years of Putin’s leadership. However, as evidenced by the declining turnout rate mentioned previously, the “stability” argument for support of Putin is waning with many Russians, especially those in the younger generation.

The main takeaway from this “sky is blue” election in Russia is that the world has another six years, perhaps longer, to prepare for what comes after Vladimir Putin. When that time comes there will be a legitimate shot at political competition in Russia, but it must be watched carefully lest the world’s largest country, and control of its immense nuclear arsenal, turns over to a more aggressive authoritarian, or worse yet, chaos.