Nick Miller teaches in the History Department at Boise State University. He studied history at Indiana University, where he received his Ph.D. in 1991. His current research focuses on the population of a region called Žumberak, in northern Croatia: its settlement patterns, immigration and emigration, religious and national identity. His publications include articles on Serbian and Croatian history before the First World War and Serbian politics and culture since 1945. He has written two books, “Between Nation and State: Serbian Politics in Croatia before the First World War,” and “Nonconformists: Culture, Politics, and Nationalism in a Serbian Cultural Circle, 1944-1991.” His articles have appeared in The Slavic Review, East European Politics and Societies,Nationalities Papers, Orbis, Problems of Post-Communism, and in edited volumes.

Overwhelming numbers of refugees and the seeming suddenness with which they appear limit our ability to understand them. As a result, refugees often appear as intractable, inscrutable problems, evoking sympathy but more often malevolent responses. We fear that which we don’t understand, goes the platitude. What might we do to better understand them? I suggest here that historians can help.

Historians have not been quick to think and write about refugees, which may reflect that they accept that the most important thing we can do for refugees is solve their problems in the present. The refugee, no matter where she is from, which language she speaks, can easily appear to have no past, with a story that is only as long as the trip she has taken from the first border she crossed. The historian’s longer view would focus less on problems and their solutions and more on cultural richness and idiosyncrasies, embracing the varieties of refugee origins and experiences rather than reducing them to simple symbols of suffering, encouraging empathy, and thus allowing us to honor and rejoice in the refugee’s resilience.

THE TRADITIONAL APPROACH: FROM EUROPEAN INNOVATION TO GLOBAL REALITY

To accomplish this, historians will have to reconsider their role in what we call “refugee studies,” which will in turn need to move beyond received twentieth-century understandings of what refugees are. In the typical introductory discussion of the phenomenon of the refugee, two phases are sketched out. The first might be labeled “the European phase.” Historians have played an important role in explaining the emergence of refugee movements from about 1870 to the immediate post-World-War-II era. In that period, the number of refugees and frequency of refugee movements grew enormously, as the idea of the nation-state with citizens and borders emerged in Europe. Nation-states, according to this plotline, created the first refugees. They were also mostly European, and political elites mostly understood them to be a natural consequence of the emergence of nation-states. Historians are traditionally good at talking about states and ideas, and they have done excellent work on this period, which ended in the years following World War II.

Later, refugee movements became something other than the results of European citizenship tests. With the achievement of statehood by former colonies in Asia and Africa, the process seen in Europe was replicated over and over again, but the instability of those new states forced us – scholars, the international community – to expand our understanding of refugees to include those who are forced across borders by political violence of all sorts, violence related to crime, gendered violence, even those who flee environmental and developmental disasters. These movements, which have resulted in more than a hundred and fifty million refugees over the past seventy years, continue to erupt. The most recent of them, the results of conflict in Syria, South Sudan, and Afghanistan, are neither remarkably large nor were they difficult to predict, yet we continue to act surprised. This period, which we could term “the global phase” in the story of refugees, demands that we ask and answer different questions, more logically addressed by social scientists than historians.

What is missing in these two phases of the discussion of refugees is the possibility that there were refugees before the modern political era. Aside from quick references to Huguenots and Jews – two peoples whose refugee status is uncontested, but mostly treated as unique – few have allowed for the possibility that refugees existed deep in the past, inside or outside of Europe. What if historians moved the discussion forward by casting their attention further backward? We can broaden our understanding of what makes a refugee a refugee. To do so, we could return to a time before international organizations created definitions to that govern international responses to refugees, and before the sheer number of refugees taxed our ability to understand them as individuals. Were we to accept the suggestion that refugees are, say, simply people fleeing the threat of physical annihilation, even in a time before legally impassable borders and defined notions of citizenship, we can begin to consider a whole range of historical examples that fall outside the range of the usual suspects.

WHAT MIGHT SUCH AN INQUIRY LOOK LIKE?

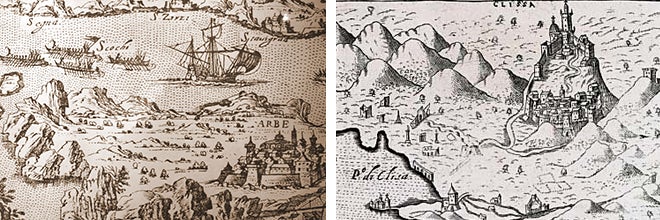

We might have the opportunity to consider the complete cycle of a refugee movement. That is, from initial move to temporary settlement, through a durable solution, and even beyond. One such movement occurred in the 1530s, when several thousand Orthodox Christians known as “Uskoks” (from uskočiti, “to jump forward,” or “attack”) fled north out of Ottoman-controlled Bosnia and into a small district known as Žumberak (what today is about twenty miles west of Zagreb, Croatia’s capital), then in Habsburg-controlled Carniola. These were refugees fleeing religious persecution, typical of their times. But certain qualities set them apart from their contemporaries in flight, Huguenots and Jews above all. These Uskoks sought opportunity, and actually negotiated their own landing place, assured by privileges that the Habsburgs were willing to grant them in return for military service. Žumberak and its refugee settlers comprised the first link in what would become the Croatian Military Frontier. The Uskok settlement of Žumberak is in its sixth century, and while most of the descendants of the Uskoks have now moved on, its outlines are still clearly visible, rendering Žumberak the longest discrete refugee settlement zone that I know of.

Once settled in Žumberak, the Uskoks and their descendants were marginalized in two ways. The first was geographic, and appeared quickly, as the region itself was almost immediately distanced from the rest of the Military Frontier, with the border between the warring Ottomans and Habsburgs settling about fifty miles south of Žumberak. The other form of marginalization was religious in nature, and came in the seventeenth century as the region’s Orthodox inhabitants converted en masse to the Uniate church – a halfway-house organization that very few other Orthodox in Croatia joined. In this isolated ghetto as lonely adherents of a marginal church, this population stayed put for centuries. Their isolation, on the margins both geopolitically and culturally, makes these refugee settlers an intriguing study.

As a case study in refugee resettlement, the Uskoks offer many useful comparisons with contemporary cases, some of them reassuringly or distressingly familiar, others not at all. Among the most familiar is that the Uskoks suffered discrimination. They dressed differently, their families were organized differently, they earned their living in ways foreign to their hosts, they seemed to threaten the livelihoods of the existing population, they came from a war zone and were therefore inevitably perceived as warlike, they allegedly (and perhaps actually) acted as spies for the people they claimed to be fleeing, and so on, all of which is clearly established in the written historical record. These responses are utterly familiar to us today as we search for solutions to, say, the Syrian refugee crisis.

The Military Frontier, like many of today’s refugee camps, served as a collection point for those who continued to flee the Ottoman Empire and also as a staging area for military forces preparing for a return to their original homeland. In this, the Uskoks bear comparison with those modern refugee exoduses that see armed forces, large or small, flee across borders to recruit and regroup in the refugee camp setting. A bit further afield from most modern refugee experience is the fact that these refugees clearly had agency – they negotiated their move, they negotiated the conditions of their settlement, and they honored the terms of their agreements scrupulously, to the point that they came to be identified with the land they settled.

In a recent article in Immigrants and Minorities (vol. 35, no. 2), the author notes the ongoing suspicion that some or all of the Uskoks were acting as informers for one or the other side.

However, these privileges, which gave them so much in the beginning and exemplified their agency, also locked them into an insular existence in a small and poor backwoods district. By the nineteenth century, when its people no longer served any military purpose, Žumberak had become known as the Uskokengebirge (Uskok Mountains), legendary for their hearty but impoverished inhabitants. Opportunity had turned to stagnation. Their identity as Žumberčani, sustained and cursed equally by their dual marginalization, came under some stress in the twentieth century as national conflict engulfed all of the people of former Yugoslavia, forcing them to choose one or the other national affiliation.

Today, the majority of the relatively small number of inhabitants of Žumberak consider themselves Croats. But among those who left in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and their descendants, a strong sense of separateness persists. The Uskok settlement has now been almost fully played out, as the vast majority of Žumberak’s inhabitants have moved on, either to urban areas in Croatia, Slovenia, and Europe, but also in many cases as small groups that continue to maintain their collective identity as Žumberčani (in Cleveland and Toronto, for instance).

CONCLUSION

The Uskok refugee movement stands as a unique opening to study a situation that shares many characteristics with movements since the Second World War. It has lasted in some form for nearly six centuries and offers an unparalleled opportunity to examine a refugee movement that has fully run its course. The Uskoks are a messy example – they compel us to think of refugees in a slightly different way than we do today and little about their story lines up perfectly with case studies we are familiar with today. But they give us food for thought we we wonder what will happen with, for instance, Palestinian refugees, stranded in camp-cities for decades, awaiting some type of solution to their unbearable suffering; or even with those for whom an arguably durable solution has been found. What might durable look like over decades and centuries rather than months or years?

Historians have been late to the study of refugee movements, and even when they have engaged, they have paid little attention to pre-nineteenth-century examples. There is much more to be learned about and from the Uskoks – and surely there are other examples from earlier times that offer similar possibilities, left ignored because they do not conform to our late-twentieth-century definitions of the refugee.