Vanessa Fry serves as the Assistant Director of the Idaho Policy Institute and Assistant Research Professor in the School of Public Service. Before joining the Idaho Policy Institute, Vanessa served as the Assistant Director for the Public Policy Research Center and Policy Innovation Fellow for the City of Boise where she conducted a feasibility assessment on using Pay for Success financing to address issues associated with chronic homelessness.

On an annual basis, the United States spends approximately $800 billion on social issues. However, one and a half decades into the 21st Century, the country continues to suffer from numerous social challenges, many of which haven’t seen improvement since the 1970s. For example:

- K-12 reading and math achievement rates have been stagnant despite 90% increase in public spending per student.

- The U.S. poverty rate has remained around 15%.

- Average yearly income of bottom 40% of U.S. households has changed little.

As a result, across the country, communities from Boise to Boston are faced with tremendous cost burdens related to persistent social issues like homelessness, lack of school readiness, and recidivism in the criminal justice system. These issues impact the public, nonprofit, and private sectors, yet bringing together the resources and knowledge of these oftentimes disparate interests is not easily accomplished. Using the issue of chronic homelessness as an example, I examine a way to coalesce these sectors and drive communities’ scarce resources toward more efficient and effective social programs.

Chronically homeless individuals are people who have been without housing for a year or more and also have a disabling condition like heart disease, substance misuse, mental health instability, or diabetes. They are people that are among the highest users of social services in the United States today. While serving as the Policy Innovation Fellow for the City of Boise I conducted an analysis of the financial and social costs Ada County faces due to issues related to homelessness. The research began with case studies of the impacts of the issue across Ada County. One of the case studies focused on a man in his mid-forties I’ll call ‘Joe’.

For much of Joe’s adult life he suffered from substance abuse – mainly the misuse of alcohol. For the last few years Joe had also been homeless. There were certainly costs to Joe and his well-being related to his substance abuse and homelessness, but the case study revealed there were also significant costs to the community.

Over a six month period, June 2015-December 2015, Joe allowed Boise Police Department (BPD) to track his interactions with the community. During that time it was found that in order to access alcohol Joe stole hand sanitizer from drug stores, bathrooms, and porta-potties. Due to the highly chemical nature of the hand sanitizer Joe often became violently ill from consuming it, requiring medical attention. As a result, in just six months Ada County Paramedics were dispatched 11 times to assist Joe. Joe also had 13 visits to a local hospital.

Because Joe stole the hand sanitizer, trespassed, and was often publicly intoxicated, he came into contact with the criminal justice system on multiple occasions. During the same six months, Joe was arrested 14 times and had 22 charges against him. He also spent 95 days in jail. The total community spending resulting from Joe’s actions were over $50,000 – and that was just from Joe’s interactions with the criminal justice and emergency medical systems.

THE COSTS OF CHRONIC HOMELESSNESS

What if there were 100 Joes in a community – a hundred people experiencing chronic homelessness? In 2015 that is exactly what Ada County was facing.

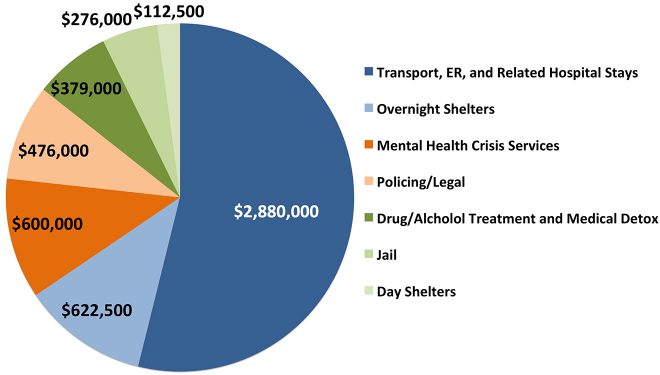

The next phase of the research estimated the reactive community spending associated with 100 chronically homeless individuals. The community had never embarked upon this calculation and there was not a system in place that systematically tracked a person’s interactions with multiple social service agencies. Therefore, collaboration with the local criminal justice, emergency medical, and shelter systems became imperative in estimating the costs. Results estimated the community costs of 100 individuals experiencing chronic homelessness in Ada County to be well over $5 million, with the vast majority of the spending related to emergency medical costs.

In conducting the analysis, it became evident that there were other costs more difficult to measure, including the economic costs to private sector businesses proximate to homelessness encampments or panhandling activities and the intangible costs a community experiences when a homeless individual dies due to exposure or other incidences. When these costs are taken into consideration the community is likely experiencing an annual cost burden well over $5.3 million.

Working across the community it became clear that regardless of sector, one clear outcome was desired – ending homelessness. That wasn’t the most common narrative people used, however. Organizations spoke about the outputs related to their specific work, like number of days in the jail or bed nights in the emergency shelter system, rather than the long-term desired outcome of ending homelessness. The community’s ability to come together to address a common goal was hindered. The actors had mindsets of scarcity regarding the limited resources available to address the specific issues their organizations were separately facing. Thus, rather than collectively using those resources to address the root causes of homelessness they were using them to pay for programs focused on the symptoms of homelessness. The result? Chronic homelessness in Ada County was on the rise, rather than on the decline.

This is just one example, but we can see the same story play out across the country.

At both the federal and local levels resources have habitually been dedicated to reactive social measures, such as policing or emergency medical services, resulting in an under-investment in prevention-related programming, even though preventative programs have been proven to be more cost-effective over the long run.

These social programs, including subsidized housing and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, are intended to ensure the most vulnerable populations’ basic needs are met. However, research has consistently shown these social programs often are not meeting society’s needs. Rather, social service spending tends to pay for a set number of services or outputs (e.g., number of nights in an emergency homeless shelter) rather than desired results or outcomes (e.g., reduction in interactions with the criminal justice system or reduction in emergency room visits). As such, outcomes are rarely assessed, which makes it challenging to identify where money is being spent on programs that are ineffective and do not work.

As a result, communities across the country are responding to the issues created by ineffective service. This high level spending on reactive measures (e.g., emergency room usage by individuals experiencing homelessness) may be avoided if the social issue were to be addressed in a more proactive fashion (e.g., providing preventative health care). However, tight budgets often prevent exploration of innovative solutions to these chronic issues. Without funding support, government has traditionally been unable to test new interventions to address the root causes of social issues, from recidivism to school readiness.

That changed in 2009 with the passing of the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act, which created the Social Innovation Fund (SIF). SIF provides the capital necessary for state and local governments to explore innovations and outcome-oriented approaches to some of the country’s most pressing social issues. One such approach, enabling the exploration of outcome-oriented social spending, is Pay for Success financing.

THE PAY FOR SUCCESS MODEL

Pay for Success (PFS) is a financing model that uses private sector and/or philanthropic capital to pay for preventative social and environmental services. The services provided are then rigorously evaluated. If the services achieve specific outcomes, then the initial investors are paid back, usually by the government entity interested in achieving those exact outcomes.

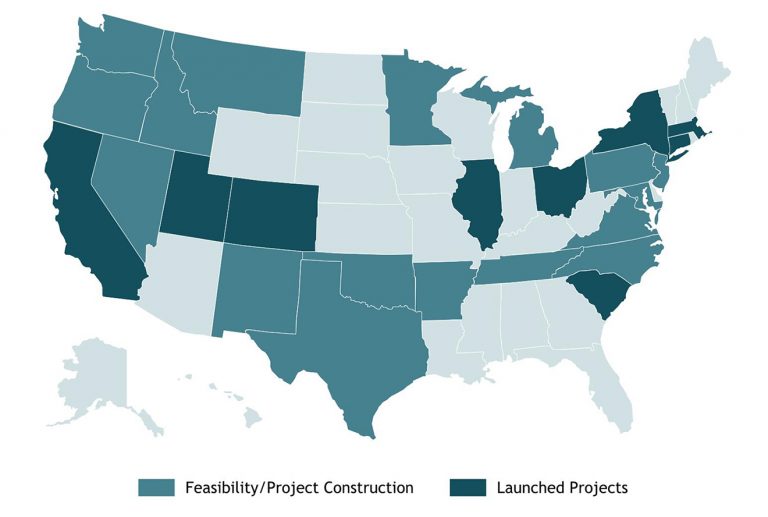

Twelve PFS projects have been launched across the U.S. in nine states and one in the District of Columbia. Dozens of other states and local governments are exploring the model’s feasibility.

In 2015 the City of Boise received funding from Sorenson Impact at the University of Utah (through a grant from the Social Innovation Fund at the Corporation for National and Community Service) to test the feasibility of using PFS to address issues related to chronic homelessness in Ada County, Idaho. A seven-fold framework, developed by Sorenson Impact, was used to guide the assessment.

When it comes to testing the feasibility of PFS, a community first must identify a persistent issue and a desired outcome relating to it. The long-term outcomes selected were reducing the interactions chronically homeless individuals were having with the criminal justice, emergency medical, and emergency shelter systems.

A PFS project must also use a proven intervention to address the chosen social issue. In 2015 Boise’s mayor, Dave Bieter, pulled together the public, private and nonprofit sectors by convening quarterly Housing and Homelessness Roundtable meetings. The group identified Housing First (download Housing in First Permanent Supportive Housing Brief pdf) as a program that had been effective in reducing chronic homelessness in peer communities, like Salt Lake County, Utah.

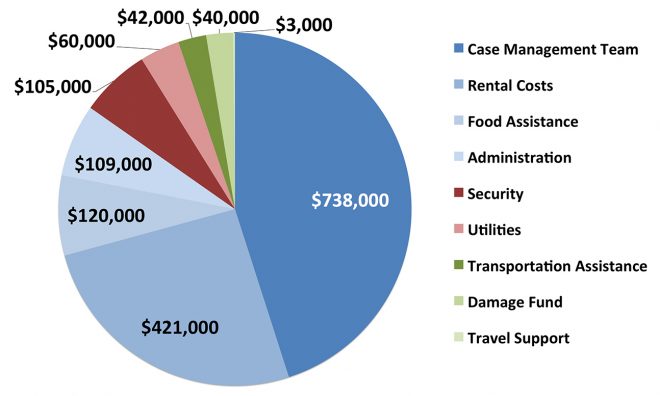

Once implemented, a PFS project should save resources while meeting the long-term desired outcomes. The assessment needed to determine what impact implementing Housing First would have on the stakeholders in Ada County. The current costs the community was facing (the $5.3 million) were compared to the costs of implementing the Housing First program, which was found to be $1.6 million annually (exclusive of one-time capital for launching the program).

Providing 100 chronically homeless individuals with a Housing First program would help decrease those individuals’ time in the emergency medical, criminal justice, and shelter systems. Based on outcomes from similar interventions, it was estimated that Ada County’s associated savings and cost avoidance from implementing Housing First could be upwards of $2.7 million annually.

With the community benefits clear, the next step was to determine where the capital would come from to implement the program. In PFS financing, a community generally raises capital for the new program in the form of an investment from the private and/or philanthropic sectors. However, rather than financing, a community can also use the structure of PFS to contract for evidence-based services, which was Ada County’s approach. Ada County stakeholders chose to scale their Housing First program to serve 40-50 chronically homeless individuals. At this level of service, the community was able to raise the money for the program solely through contributions by the public and nonprofit sectors.

Once implemented, the outcomes of the Ada County/Boise Housing First intervention will be rigorously evaluated to determine the realized outcomes, actual savings, and costs avoided. If proven successful, the community may look to private sector and philanthropic investors to finance scaling up of Housing First to serve all of Ada County’s chronically homeless population. These investors would be paid back their principal with interest from the savings incurred due to a successful program. As in any PFS financing project, if the program is not successful, the investors would not be paid back.

PFS can support the achievement of measurable outcomes while reducing the social and financial costs to a community. PFS projects help rally a community around a shared long-term outcome and can be utilized to address the root causes behind social issues such as teenage pregnancy, recidivism, school readiness, and childhood asthma.

Pay for Success mandates balancing the interests of multiple sectors in a way where communities come together to address a common goal. This balance can shift the paradigm of reactive social spending and help communities use limited resources in a more productive, efficient, and effective way. PFS can support fiscal responsibility and social well-being and be an effective tool to help increase our children’s literacy, reduce our nation’s obesity, decrease the number of people in the criminal justice system, limit teenage pregnancy, and, yes, end homelessness.