Marc C. Johnson served as press secretary and chief of staff to Idaho’s only four-term governor Cecil D. Andrus.

This essay is adapted from a short course on the McCarthy Era in Idaho that the author taught at the Osher Institute at Boise State in April.

The short period from 1947 to 1956 may well have been the most tumultuous and also the nastiest period in Idaho political history. In under a decade, eight different men represented Idaho in the United States Senate, four incumbent senators — two from each party — lost re-election, the state was represented three times by appointed senators, two incumbents died in office and one senator, Glen Hearst Taylor, one of the few Democrats ever elected to the Senate from Idaho, bolted his party in 1948 and ran for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket.

The period produced an intense focus on anti-Communism and two Idaho Republican Senators became among the most devoted followers of controversial Wisconsin Senator Joseph R. McCarthy. The McCarthy Era in Idaho did not last long, but it left a mark on the state’s politics for generations.

November 7, 1950 — election night — and the junior senator from Wisconsin, Joseph Raymond McCarthy, is celebrating. From California to Illinois, from Utah to Maryland, McCarthy’s high profile hunt for Communists in the federal government, launched only the previous February, has been key to Republicans winning a half dozen U.S. Senate races and now McCarthy has new allies ready to help him press his attacks.

In Maryland, McCarthy helped engineer the end of Democratic Senator Millard Tydings’ 24-year career, getting even with Tydings for having dismissed as “a hoax and a fraud” McCarthy’s allegations that “known Communists” had burrowed deeply into the U.S. State Department. McCarthy responded to Tydings’ dismissal of his crusade by both getting mad and getting even. McCarthy labeled Tydings, a decorated World War I veteran and conservative Democrat who was often at odds with Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, an agent of the international Communist conspiracy. His staff created and circulated a composite photo of Tydings appearing to show the senator in conspiratorial conversation with the head of the U.S. Communist Party. The photo was a brutal smear, but also extremely effective. Tydings was swamped.

In California, Congressman Richard Nixon, a member of the House Committee on un-American Activities, a young politician already possessed of a national reputation as a Commie hunter, also won a Senate seat in 1950. Nixon disparaged his liberal opponent, Democratic Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas, never quite calling her a Red, but as Douglas said, creating “the impression that I was a communist or at least communistic.” A “pink sheet” circulated during the campaign that catalogued Douglas’ alleged “communistic” positions. Nixon won in a walk.

In Utah, Republican Wallace Bennett attacked three-term Democratic Senator Elmer Thomas, a history professor and Asia expert, for having “communist” positions. Pamphlets circulated charging the one-time LDS missionary with belonging to various Communist front organizations and suggesting Thomas’ foreign policy views were influenced from Moscow. Bennett won 54 percent of the vote.

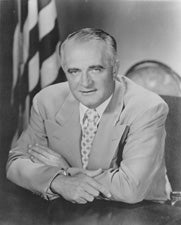

But it was in Idaho in 1950 that McCarthy really scored. Due to the death of Idaho Democratic Senator Bert Miller in 1949, Idaho experienced a political rarity a year later — two Senate elections in the same cycle — and that anomaly allowed Joe McCarthy to enlist both of Idaho’s senators, staunch conservatives Herman Welker and Henry Dworshak, in his anti-Communist cause. Welker became so identified with McCarthy that reporters dubbed him “Little Joe from Idaho” and Welker was referred to as McCarthy’s best friend in the Senate. But just six years later McCarthy’s tactics, as well as Welker’s, had alienated many voters, including many Republicans, and the McCarthy Era came to a sputtering end. Still, for a short time in the early 1950s, with the consistent support of both of Idaho’s senators, McCarthy and his virulent anti-Communism wielded enormous political influence in Idaho.

As McCarthy biographer Thomas C. Reeves wrote, “People whooped and cheered” as they celebrated the 1950 election results from Idaho and elsewhere during a boozy victory party at a house in the Virginia suburbs At one point during the evening the septic tank backed up flooding the floors and the Communist-hunting senator from Wisconsin and other guests were observed, “wading through the overflow in their bare feet. The symbolism somehow escaped him.”

Post-World War II Idaho politics were unpredictable, intraparty challenges were common, partisanship, often exemplified by newspaper treatment of candidates, was extreme and anti-Communism, a defining theme of the period, was often an emotional, divisive and decisive issue. The turmoil produced some notable political characters, brought to an end the colorful and controversial career of perhaps the most liberal politician ever elected in Idaho, Democratic Senator Glen Hearst Taylor, and remarkably, particularly considering Idaho’s partisan make-up today, helped launched the unlikely political career of Senator Frank Church.

THE SINGING COWBOY

Glen Taylor launched his improbable political career under a big Stetson hat with a guitar in his hands. Raised as the 12th of 13 children on a farm near Kamiah, Taylor’s father was a preacher and young Glen, sporting no more than a sixth grade education, came early to his skills as an actor, entertainer and political evangelist. With his wife, Dora, Taylor created The Glendora Ranch Players, a traveling theater group that eventually transitioned into a country western band. Taylor’s colorful musical troupe and his skill as a showman created his entre into politics, but it was the Great Depression of the 1930s, with devastating levels of unemployment, impoverished families and widespread political upheaval that radicalized Taylor and pointed him toward Washington, D.C. “Once a farmer brought his five youngsters, three fryers, and a sack of potatoes to a show,” Taylor’s biographer F. Ross Peterson wrote. “The farmer asked Taylor which he would take to let the kids see the play — chickens or potatoes. Taylor looked longingly at the fryers, then said, ‘I’ll take the potatoes — they’re more filling.’”

The Taylor family eventually settled in Pocatello where the band secured a weekly radio show on KSEI and Taylor plotted his first political campaign, a race for Congress in 1938. Running as a liberal Democrat he lost — badly. He ran again in 1940, this time for the Senate, and again lost. Launching yet another Senate campaign in 1942 Taylor told reporters, “Dora and I decided we could save rubber and gas if, instead of using our car to campaign, I were to saddle up and ride around the state.”

The horseback campaign was an attention-catching gimmick, but Taylor lost yet again. Like most good politicians, however, he learned from defeat. He sharpened his message, focusing on economic fairness and a decent shake for the little guy and he identified enemies, particularly Idaho Power Company and Morrison-Knudsen, the big Boise-based engineering firm. The ambitious candidate also addressed what he considered to be an image issue — his growing bald spot, a physical feature that Taylor was convinced made him look older than his age and was impacting his political appeal. His solution was both novel and eventually lucrative. Using an old tin pie plate Taylor fashioned a skullcap of sorts, attached hair and constructed a serviceable hairpiece, the first of what would become the “Taylor Topper.”

In 1944, with national attention turning to the shape of the post-war world and particularly the creation of the United Nations, Taylor, an unabashed liberal internationalist, ran again for the Senate against incumbent Democrat Senator D. Worth Clark. A conservative Democrat often at odds with Franklin Roosevelt’s foreign policy, Clark was a solid favorite in the primary, but Taylor had matured as a candidate after three losing campaigns. The horse and the Stetson were mostly retired and Taylor was a skilled stump speaker who could still entertain a crowd with a song. The Idaho writer Vardis Fisher remembered Taylor as “one of the greatest speakers of our time.” Fisher said he listened to Taylor “every time I get a chance, not because he ever says anything, but because he says nothing superbly.”

Clark, the incumbent and scion of a legendary Idaho political family — his cousin was Bethine Church, the wife of the future senator, and two of his uncles served as Idaho governors — should have made short work of the three time loser, but it was Clark who lost the Democratic primary by 216 votes. Taylor, with FDR leading the ticket in Idaho, then dispatched the Republican candidate, Governor C.A. Bottolfson in the 1944 general election. The Singing Cowboy was in the Senate.

Almost immediately Taylor established himself on the far leftwing of the Democratic Party. He was pro-United Nations, favored national health insurance, advocated a Columbia Valley Authority modeled on the Tennessee Valley Authority, argued for more western reclamation projects, better housing for veterans and creation of a Fair Employment Practices Commission. Taylor eventually broke with President Harry Truman (Truman became president upon the death of Roosevelt in April 1945) over Truman’s increasingly hard line against the Soviet Union and a lack of progress on civil rights. In 1948, only three years into his Senate term, Taylor left the Democratic Party to run with former Vice President Henry Wallace on the left-leaning Progressive Party ticket.

Taylor’s rejection of the Democratic Party, his internationalist foreign policy views and his outspoken support for civil rights — Taylor was arrested in Birmingham, Alabama in 1948 for entering a building through a doorway marked “colored only” — further cemented his reputation as a radical. Taylor’s positions played into the developing political narrative in Idaho that he was at best a dupe of the Communists, or at worst a genuine fellow traveler, particularly after the Progressives refused to repudiate support from socialists and Communists in the 1948 campaign. The Progressive ticket was crushed in the presidential race and even Taylor couldn’t prevent an embarrassing loss in Idaho. The Wallace-Taylor ticket gathered in fewer than 5,000 votes in Idaho, a dispiriting showing for a senator who needed to face voters in his own re-election in 1950.

“I HAVE HERE IN MY HAND…”

On February 9, 1950, McCarthy was the featured speaker at a Republican Party dinner in Wheeling, West Virginia. As a first-term backbencher elected in 1946, McCarthy was little known beyond Wisconsin or the Senate, but after his headline grabbing Wheeling speech he became, almost overnight, the most famous senator in the country. Perfecting the politics of fear and alienation that would soon attach his name to an era, McCarthy told his audience that Americans faced a grave threat — enemies from within:

The reason why we find ourselves in a position of impotency is not because our only powerful potential enemy has sent men to invade our shores… but rather because of the traitorous actions of those who have been treated so well by this Nation. It has not been the less fortunate, or members of minority groups who have been traitorous to this Nation, but rather those who have had all the benefits that the wealthiest Nation on earth has had to offer… the finest homes, the finest college education and the finest jobs in government we can give.

This is glaringly true in the State Department. There the bright young men who are born with silver spoons in their mouths are the ones who have been most traitorous…

I have here in my hand a list of 205… a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department…

McCarthy never produced an actual list of “known Communists,” but his sensational allegations generated page one headlines from coast to coast and his brief and destructive career as the best-known demagogue of the Cold War was launched. Just 18 days after the Wheeling speech, Glen Taylor became one of the first politicians in the country to call McCarthy out. He denounced the Wisconsin senator’s wild accusations on the Senate floor and expressed hope that the public would “rise up and demand an end to it all.”

THE BITTER ELECTION OF 1950…

But rather than an end to the climate of fear and character assassination, Taylor was about to experience the full effect of McCarthy’s tactics. Democrats and Republicans alike assaulted Taylor. His loyalty was attacked. He was accused of being the voice of Soviet Russia on the Senate floor. “All the candidates, with few exceptions” University of Idaho historian Boyd Martin wrote at the time, “were running against Taylor. This was especially true of Herman Welker.”

Republican Welker, a 43-year old Payette attorney and former prosecutor, served only a single term in the state senate before seeking the U.S. Senate seat. Welker largely ignored his Republican challengers in 1950, including former Governor C.A. “Doc” Robins, in order to concentrate his fire on Taylor. Welker even demanded that Taylor debate him before either man had won his own party’s nomination. When Taylor ignored the debate demand, Welker said the incumbent senator was afraid to face him because “he knows I would hang his hide on the fence… and expose his communist-line activities.”

During a July 4 speech in Eastern Idaho, Welker took a page directly from McCarthy’s playbook and announced that there were “87 communists in Idaho.” He never explained how he knew the exact number, but Welker assured his listeners that among Taylor’s supporters were “radicals and stooges and crackpots who consistently follow the party line and play into the hands of the communist cause.”

Democrat Clark joined in the character assassination, saying of Taylor that, “a public official does not need to be a card-carrying communist to be a stooge or dupe.” The former senator accused Taylor, the incumbent senator of his own party, of being “duped by communists into playing their game at the expense of Americanism.”

The Idaho Statesman was unrelenting with its attacks on Taylor and likely played a decisive role in his defeat. John Corlett, the paper’s long-time and highly regarded political editor, admitted years later that the 1950 campaign was the only time in his career that he set out, “under the direction of my publisher and editor, to destroy a person and that person’s philosophy.” Day after day in advance of the Idaho primary the Statesman hammered away at the fiction that Taylor was a Communist agent or at best a naïve Communist stooge. Taylor, the newspaper asserted, represented “the Russians on the floor of the United States Senate.”

Taylor, his typically strong support from organized labor diminished by a third Democratic candidate in the primary who also enjoyed labor support, could not survive the onslaught and Clark narrowly won the Democrat primary, reversing the outcome of six years earlier. One national magazine noted that the Singing Senator had been sent back to his guitar, while Welker, the beneficiary of the building anti-Communist sentiment in Idaho and the nation, defeated former Senator Clark in the general election. Taylor left the Senate dead broke with few employment prospects and he soon left Idaho for California in order to find employment as a sheet metal worker.

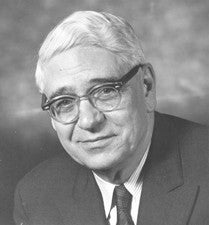

Idaho’s other Senate race in 1950 featured less drama, but also produced a McCarthy ally. Former congressman and appointed senator Henry Dworshak of Burley won a close election against Ricks College political science professor Claude Burtenshaw. Burtenshaw, a Democrat, attempted to out-McCarthy his Republican opponent and accused Dworshak of “playing the Kremlin’s game” by voting against the Marshall Plan and U.S. aid to Greece and Turkey, but the Republican, seen as the more natural McCarthy ally, won the race.

LITTLE JOE FROM IDAHO

Senate observers immediately identified Welker as “a committed McCarthyite.” A national magazine profile played off Welker’s anti-Communism and his University of Idaho connections with a headline that read “The Senator from Moscow (Idaho).” The favorable piece in The American Mercury said Welker “represents a large segment of the American people to whom nationalism isn’t an ugly word.” The Idahoan was “against the Communists and their camp followers, the Socialists, New Dealers and one-worlders.” Welker landed seats on the influential Judiciary and Armed Services Committee and honed his reputation as a slashing, tough debater, but his focus on hunting for Communists left little time to cater to Idaho interests. Beyond helping the Washington Senators baseball team sign a promising young ballplayer, Payette High School’s Harmon Killebrew, Welker had little to brag about back home.

As McCarthy turned attention to his own 1952 re-election in Wisconsin, Welker was front and center at a tribute dinner for McCarthy in Milwaukee. The Idahoan heaped praise on his Senate colleague and warned that “subversives” were bent on defeating his friend. McCarthy won re-election relatively easily while nationwide voters installed Republican Dwight Eisenhower in the White House. Yet, even the new GOP administration failed to blunt the McCarthy-Welker hunt for Communists in government, with both senators offering pointed critiques of Eisenhower’s handling of foreign affairs and particularly Communism.

Welker and McCarthy even accused long-serving presidential advisor Arthur Dean of communist sympathies.

McCarthy alleged that the United States Army manufactured a huge cover up of Communists in the military, while Welker launched a slashing attack on the American diplomat who led negotiations with Chinese and North Korean Communists at the end of the Korean War. Welker’s target was Arthur Dean, a pillar of the eastern Republican establishment and a law partner of Eisenhower’s Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. Following his diplomatic stint in Korea, Dean commented in a newspaper interview that “there is a possibility the Chinese Communists are more interested in developing themselves in China than they are in international Communism. If we could use that as a decisive method of putting a wedge between the Chinese Communists and the Soviet Union, I think we might try it.” Dean continued, “I’m 100 percent anti-Communist, but if short of military operations there is a chance of dividing Communist China from Russia, we ought to take a look at it…”

Welker, a member of the Senate’s Internal Security Subcommittee, pounced. Dean was offering the view, the Idahoan said, “held by pro-Red China apologists in the State Department.” Welker dismissed out of hand Dean’s notion that Chinese Communists might be more focused on developing their country than in advancing international Communism. “I can’t believe anything can be farther from the truth,” Welker said. Dean, he contended, was peddling thinly disguised Communist disinformation.

Welker probed Dean’s association with the Institute of Pacific Relations, an Asian-focused think tank, amid unsubstantiated allegations that Communists populated the institute’s staff. Dean subsequently spent weeks defending himself, forced to respond to questions about his associations and denying that he was sympathetic with Communism, all for suggesting that the United States might consider a more nuanced approach to dealings with China. Welker concluded that Dean’s record failed to display “any outstanding shrewdness in his understanding of the devious ways of the Communists.”

Welker’s attacks on Arthur Dean were a classic case of constructing a political mountain from the microscopic grains of a molehill. When Dean died in 1989 the New York Times noted that for more than three decades he had “served as a negotiator and adviser to Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson. He was credited with helping to persuade Lyndon B. Johnson to stop the bombing of North Vietnam in 1968 and to not seek re-election.” Dean also served as the U.S. delegation chief to the talks that eventually produced a partial nuclear test-ban treaty in 1963. Arthur Dean, labeled a pro-Communist apologist by Welker in 1954, was clearly no Communist, but rather a consummate public servant called upon for years by presidents of both parties to handle sensitive diplomatic tasks.

McCarthy’s persistent attacks on the Army that same year prompted a Senate investigation of his charges. Since McCarthy could hardly continue to chair his Permanent Committee on Investigations, in effect investigating his own allegations, he temporarily stepped down. Idaho’s Dworshak, who subsequently played only a minor role in the infamous Army-McCarthy hearings, assumed McCarthy’s seat on the committee. The Army-McCarthy hearings might well have ended in inclusive confusion had McCarthy not gratuitously attacked the background of a young attorney only tangentially connected to the investigation and had McCarthy’s own controversial counsel, Roy Cohn, not become embroiled in allegations that he sought favorable treatment from the Army for a friend. When Cohn, a polarizing figure until the end of his life and in the 1980s an early political mentor of Donald Trump, eventually resigned as McCarthy’s lawyer, Welker praised him on the Senate floor as the most brilliant attorney he had ever met.

The real import of the Army-McCarthy hearings was live television. For the first time, and for an extended period, the American public actually saw McCarthy in action — his mocking tone, disdain for facts and remarkable and cynical ability to turn any criticism into an attack on the motives of his critics. The impact on the public and the Senate was enormous and a handful of Senate Republicans finally moved to confront McCarthy’s excesses. A motion to censure the Wisconsin senator was introduced and a select committee, chaired by Utah Republican Arthur Watkins, opened an investigation. McCarthy, in keeping with his by now well-practiced methods, condemned the Watkins Committee as nothing less than enablers of the vast Communist conspiracy. Welker meanwhile suggested publicly that if his friend McCarthy was to be censured he should be censured, too.

TAYLOR RIDES AGAIN

Meanwhile in Idaho, Glen Taylor, hoping to regain his Senate seat, mounted up for one more campaign, this time against Henry Dworshak. Welker was not on the ballot in 1954, but he nonetheless played an outsized and likely decisive role in Dworshak’s campaign against Taylor. In a series of appearances across the state Welker attacked Taylor just as he had four years earlier, assailing the former senator’s ties to the Progressive Party and suggesting the one-time cowboy guitarist was dangerous and un-American. Taylor was, Welker said, one of “the Communist Party’s most pathetic and willing dupes.” Vice President Richard Nixon joined in the assault while campaigning before a crowd of 2,300 in Pocatello, calling Taylor “a dedicated left winger.” Nixon’s rebuke was mild compared to some of the more incendiary things Welker alleged.

Taylor struggled to defend himself, admitting he was an unabashed liberal, but no Communist. He appealed, unsuccessfully, to his opponent Dworshak to denounce the smear campaign. The attack on his loyalty, Taylor said, “out does anything ever attempted by Joe McCarthy in violating every American’s idea of decency and fair play.” Some political observers thought Taylor’s skill on the stump and the loyalty of his core supporters might be enough to blunt the sustained attacks, but the overwhelming negative barrage swamped any appeal for reason and fairness. Dworshak coasted to a 60,000-vote victory and Taylor’s political obituary was written once again – once again prematurely.

CENSURING MCCARTHY

During the post-election lame duck session of Congress in 1954, with some Senate Republicans determined to head off a bruising intraparty fight over McCarthy’s censure, attempts where made to work out some type of accommodation that might avoid a nasty, public showdown. If McCarthy apologized for his comments about the Watkins Committee, for example, the push for censure might well have been blunted. McCarthy was reportedly interested in such a face saving move, but several of his supporters, especially Welker and Indiana senator Republican William Jenner, were adamant that there could be no retreat.

McCarthy, saying he did not want to disappoint his friends and perhaps realizing that supporters like Welker and Jenner had come to believe even more than he in his anti-Communist crusade, agreed to fight the censure resolution on the Senate floor. The outcome was a foregone conclusion, although the contentious debate took days to play out with Welker quarterbacking McCarthy’s defense. As the vote neared, Welker was reported to have wandered about the Senate chamber mumbling obscenities under his breath. Ultimately 22 senators, including Welker and Dworshak, opposed McCarthy’s censure, while 67 voted in favor. Joe McCarthy became only the fifth United States senator to officially have his conduct condemned by his colleagues.

The censure resolution accelerated the pace of both McCarthy’s personal and political decline and the arc of Welker’s career followed that of his friend. Welker’s repeated attacks on the Eisenhower Administration, his apparent indifference to Idaho issues and his increasingly erratic behavior — rumors circulated of a drinking problem and it was only later discovered that Welker suffered from a brain tumor — took a toll. By the time Welker faced re-election in 1956 he was so unpopular among Idaho Republicans that he drew four primary challengers and won re-nomination with only 42 percent of the vote. Welker’s showing in Eastern Idaho was particularly dismal — he was held to under 10 percent of the Republican vote — and would help seal his general election defeat.

The Democratic Party primary in 1956 featured just as much, if not more, turmoil, with Glen Taylor making his seventh run for federal office. As the best known contender in a four candidate Democratic primary, Taylor seemed to have an edge, but the contest came down to a slugfest between the old liberal fighter and a fresh faced newcomer. Thirty-two year old Frank Church — he looked even younger — was the newcomer. A Boise lawyer with a polished and effective speaking style, Church ran a spirited, positive campaign largely avoiding the overarching issue of McCarthyism and focused instead on Idaho’s economic development.

Taylor responded by accusing Church of being a tool of big business, perhaps the first and only time that charge was leveled, and for being only “a high school orator.” For his part, Church, who had won a high school speech contest, counted on winning the Democratic nomination by appealing to Idaho Democrats who had grown weary of Taylor repeatedly running and losing. His political calculation was precise and Church defeated Taylor in the primary by the uncomfortably close margin of 170 votes. Taylor immediately alleged that Church, thanks to his connection to the Clark political dynasty, had stolen the election through the machinations of the “Clark Machine.” Taylor’s personal door-to-door canvasing in Elmore County failed to develop convincing evidence of voting irregularities and an appeal to the Senate went nowhere. Still, the old campaigner refused to give up and mounted a write-in effort in the general election, a write-in campaign Taylor admitted in his memoir that his campaign had been financed to the tune of $35,000 by Welker supporters who were convinced Taylor would draw votes from Church in a three-way race. Considering all the grief Welker had dealt him over the years, Taylor said the financial help was the least Welker could do.

Beyond his support for McCarthy and his own redbaiting experience — “a bruising political infighter who kept an eye on the jugular,” as Church’s biographers have written — Welker lacked a compelling record. One newspaper editor said an album of Welker’s legislative accomplishments would be nothing but empty pages. Welker fell back on what had always worked in the past — he attacked Church as a tool of “radical pinks and punks.” But this time the redbaiting attack fizzled.

Welker attempted to make an issue of Church’s endorsement by the National Committee for an Effective Congress, a group organized by Eleanor Roosevelt in 1948, that Welker described as a financial conduit that would allow Communist money to influence Idaho politics. Church, effectively using television advertising for the first time in Idaho, cleverly responded that Taylor had branded him a tool of big business, while Welker called him a Communist stooge — both could not possibly be correct. Welker even suggested the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 school desegregation ruling was not merely Communist inspired, but that Communists “wrote it.”

Young Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy campaigned for Church, as did the Democratic vice presidential candidate Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee. Newspaper advertisements implored Idahoans to elect a “sane and sober” senator and one Church radio jingle, set to the tune of “Get Along Little Doggie” suggested it was time to “get along without Herman.”

After managing less than 38 percent of the vote in the Democratic primary against Taylor and two other candidates, Church piled up more than 56 percent of the vote — a stunning 46,000 vote margin — over Welker, with obviously many Republicans backing the Democrat. Remarkably, Taylor’s write-in campaign drew more than 13,000 votes. He claimed he had spent more money — money supplied by Idaho Republicans — in the write-in effort than in any of his other campaigns. Nationally, the defeat of an incumbent Republican in Idaho, particularly one considered “McCarthy’s best friend in the Senate,” was viewed as a stunning upset. The New York Times described the new Idaho senator as a “pink cheeked attorney, scarcely older than a boy out of college” and Boyd Martin, the University of Idaho political scientist, wrote after the election that, “Both parties appeared pleased with the final results. In one election Idaho’s two most controversial figures, Taylor and Welker, had fallen.”

McCarthy, who did not personally campaign for his friend, publicly blamed Eisenhower for Welker’s loss even though several administration figures, Vice President Nixon for example, made Idaho appearances and the president sent Welker a “Dear Herman” letter that served as an official endorsement. Eisenhower, “a so called Republican president,” in McCarthy’s view, was guilty of “purging” Welker, in retaliation, McCarthy said, for the Idahoan’s attacks on the administration.

A little over a year later McCarthy was dead. He was just 49. Welker was in a small delegation that made the trip to Appleton, Wisconsin for the funeral. Six months later Welker, just 50-years old, was also dead of the brain tumor that likely went undiagnosed for some time. Henry Dworshak, twice appointed and twice elected to the Senate during Idaho’s post-war years of political turmoil remained a staunch anti-communist and one of the Senate’s most conservative members until his death in 1962. Asked in 1955, a few months after McCarthy’s censure, what had become of “McCarthyism,” Dworshak seemed surprised. “McCarthyism? Haven’t heard anything about that lately. I thought we had done with that at the last session,” he said.

Glen Taylor’s political career finally ended in 1956. He moved permanently to California and made a handsome living manufacturing and selling his Taylor Topper hairpieces. In a memoir published in 1979 Taylor continued to argue that Church had somehow stolen the 1956 primary, but he also admitted that his post-political life had finally allowed the financial security that he had never before enjoyed. Taylor contended he never regretted running for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket, even if that decision and the resulting wild allegations about his supposed Communist sympathies contributed to the end of his Senate career.

The McCarthy Era lost its champion with the death of the Wisconsin senator in 1957 and McCarthy’s influence in Idaho faded with Welker’s defeat in 1956, but echoes of this short and intense period in the late 1940s and early 1950s lingered for decades.

Frank Church went on to serve four terms in the Senate, leaving a legislative and investigative record that continues to draw both praise and scorn. It is a rich paradox of Idaho political history that Church won his first Senate election in 1956 by defeating an ultra-conservative McCarthyite and lost his last race in 1980 amid allegations that his support for the Panama Canal treaties and his illuminating and historic investigation of the Central Intelligence Agency played into the hands of the country’s Communist adversaries.

As journalist and historian Adam Hochschild has noted, “a curious thing about the United States is that anticommunism has always been far louder and more potent than communism.” Unlike other developed democracies — France, Italy and India for example — American Communists have never enjoyed any significant political success. Even with Communist support in 1948, the Henry Wallace-Glen Taylor Progressive Party ticket managed only 2.4 percent of the national vote. Anticommunism, on the other hand, remained a potent political force for nearly half a century and propelled politicians like Richard Nixon, Joe McCarthy and Idaho’s Herman Welker to national prominence and the allegation that an opponent was “soft on Communism” remained a powerful talking point for Idaho Republicans, literally until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

At the same time the excesses of the McCarthy Era Communist hunting zeal frequently led to a fear and coarseness in our politics and our culture that was often not only profoundly unfair — Glen Taylor is a case in point — but also frequently served to keep the country from more positive and arguably more important pursuits.

Tucked away in the decades of correspondence, speeches and committee reports that constitute Church’s voluminous Senate papers is an opposition research memo prepared by his campaign in 1956. “The Welker — McCarthy smear team swaggered though a nightmare of falsehood and terror,” the paper concluded, “the time has come to pass judgment on one of the chief trigger men of these un-American political mobsters.” That description, portraying the disciples of 1950s McCarthyism as the real un-Americans, provides an enduring lesson from the McCarthy Era. Fear, distrust, incivility, the simple answers to complex problems that can make demagogues like Joe McCarthy and his disciplines both attractive and dangerous, remain features of our politics now just as they were more than 60 years ago. And sadly, the skillfully stoked fears of a demagogue often work as well today as they did in the 1950s.