Eiichiro Tokumoto, a former Reuters correspondent, is an author and investigative journalist in Tokyo, Japan.

This article has been translated by the author and is reprinted with the permission of Shukan-Shincho Weekly Magazine. The original article, in Japanese, can be found on the Daily Shincho website.

INTRODUCTION BY GARRY V. WENSKE

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the investigations by the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Multi-National Corporations, chaired by Idaho’s Senator Frank Church. The Committee’s investigations of bribery of foreign officials by major U.S. corporations resulted in the arrest of Prime Minister Tanaka of Japan.

A recent article in Japan’s Shincho Magazine by Eiichiro Tokumoto, an investigative journalist, who used the Frank Church Collection at Boise State for some of his research, concluded that Church was “the man who pulled the trigger to unleash the Lockheed scandal, the biggest political scandal in postwar Japan.” The Frank Church Collection at the Boise State University Library contains one of the largest collections of its kind and has been used by thousands of researchers as a source of documentation.

Garry V. Wenske is Executive Director of The Frank Church Institute at Boise State University and former Legislative Counsel to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee chaired by Senator Frank Church.

FLASH POINT OF THE LOCKHEED SCANDAL REVEALED FOR FIRST TIME

Boise, the state capital of Idaho, is a city of some 200,000 located near the junction of the historic Oregon Trail, about 90 minutes by plane from San Francisco. Its natural surroundings project a relaxing atmosphere quite unlike a large metropolis such as New York. Outside of the city spread over grassy hills can be found the Morris Hill Cemetery.

In June of this year, under sunny skies of early summer, I stood quietly before a gravestone, upon which several small wreaths had been placed. The memorial was inscribed with the words FRANK CHURCH, 1924-1984. It is the final resting place of former U.S. Senator Frank Church, a Boise native. Once regarded as one of the city’s greatest native sons, it shows that he is still respected even today.

Forty years ago, Church was “the man who pulled the trigger” to unleash the Lockheed Scandal, the biggest political scandal in postwar Japan, which led to the arrest of former Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka.

On February 4, 1976, when Church was serving as chairman of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Multinational Corporations, under the Foreign Relations Committee, it was revealed that U.S. aircraft maker Lockheed Aircraft Corporation had earmarked over three billion Japanese yen in secret funds to sell planes to Japan.

The payoffs, for the purpose of selling the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar passenger jets to All Nippon Airways, were made in the form of bribes distributed to high-ranking government officials by right-wing fixer Yoshio Kodama. Also involved in the scandal was Kenji Osano, a businessman known for his political connections, and the Marubeni trading company, which represented Lockheed sales. The code name “Peanuts” was used on receipts to indicate payoffs. At hearings of the Church committee, Lockheed’s vice chairman A. Carl Kotchian testified that a total of approximately $2 million (nearly 600 million yen) had been distributed to Japanese government officials through Marubeni.

The question of who had accepted the money set off a storm in Japan, which on July 27 culminated with Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office’s arrest of former Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka on suspicion of violating of the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act. It was the first time in history of a person who had held the post of prime minister being arrested for a crime committed during his tenure. It was Washington, and Chairman Frank Church, who acted as the flash point to what became known as the Lockheed Scandal.

For that reason, perhaps, speculation still persists in Japan concerning details of the scandal, to the degree of conspiracy theories circulated to the effect that the U.S. government sought to oust Tanaka. What was the Lockheed Scandal really about, and what actually happened in Washington at that time? More than anyone, those details would have been known by Frank Church.

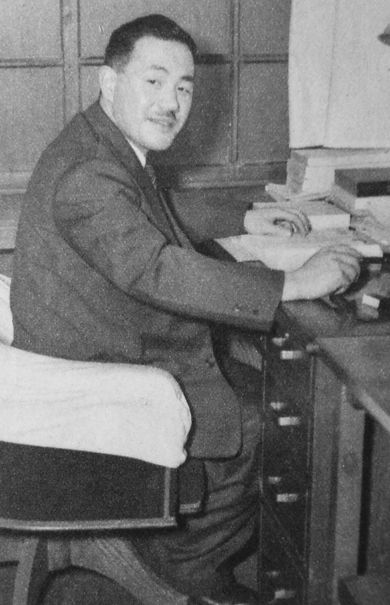

Born in Boise in 1924, Church was influenced by his father, the owner of a sporting goods store who harbored a strong interest in politics. After graduation from a local high school he matriculated at Stanford University, and during the Second World War served as a U.S. Army intelligence officer assigned to Asia. After the war Church earned a degree in law, and in 1957, at the relatively young age of 32, was elected to the U.S. Senate.

During his time in the Senate, Church began speaking against the war in Vietnam and American policy in Southeast Asia. During the 1970s he was tabbed to chair the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, which disclosed Central Intelligence Agency plots of assassinations of foreign leaders. In 1976 Church announced his candidacy for president of the United States on the Democratic ticket, but lost the nomination to Jimmy Carter. Following his defeat for reelection to the Senate by a Republican rival, he withdrew from politics, but remained in Washington D.C. where he practiced law. From his record he stood out as a staunch liberal Democrat.

As he succumbed to pancreatic cancer in April 1984, he cannot, alas, answer any questions concerning the Lockheed Incident.

In Church’s stead, however, a former subordinate agreed to be interviewed. His name was Jack Blum, and he served as associate counsel of the Church committee as well as a leading investigator of the Lockheed case.

LOCKHEED’S MANAGEMENT CRISIS

A native of New York who is currently age 75, Blum became a member of the investigation staff of the U.S. Congress after graduating from university, and was in his mid-30s at the time he was involved with the Church committee. He went on to become a veteran investigator into white-collar financial crime. Blum recalled the details of the Lockheed Incident of over lunch in a restaurant in a Washington D.C. suburb.

According to Blum, the Church committee had investigated several multinational corporations including Gulf Oil and Exxon. Among aircraft manufacturers it had initially focused on bribery activities not by Lockheed, but Northrop Corporation.

“When we were investigating payoffs by Northrop in foreign countries around June 1975, its president testified that they used Lockheed as a model. We were investigating fighter planes, but it turned out that in Japan it was a commercial plane, the L-1011.”

Then the committee members became excited over an unexpected development, and Lockheed and U.S. government organs were immediately requested to submit information. The late Senator Church had bequeathed his personal correspondence and documents to Boise State University, and they contained documents related to the Lockheed investigation. Looking at declassified documents of the Gerald Ford administration from the time of the scandal, and combining them with the statements of Jack Blum from my interview brought created a vivid image of what had transpired.

On August 15, 1975, about six months from the time the scandal came to light, Senator Church sent a letter to William Proxmire, chairman of the Senate committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, requesting his cooperation. It read: “The foreign activities of the Lockheed Corporation came to our attention in early June during hearings on Northrop Corporation and we began an active investigation. A subpoena was issued and we received a substantial number of documents…Lockheed’s sorry record raises the very serious question of whether the company has withheld material information from your Committee in seeking the loan.”

On the 27th of the same month, Church also sent a letter to the president of the Export-Import Bank, asking him to provide all materials relating to the export of the L-1011 and other aircraft. Why did Church contact an organization so out of its field? One may have harbored some suspicions over the loan, but behind the matter Lockheed was in the midst of a deep financial crisis.

At the start of the 1970s the U.S. government launched an organization called the Emergency Loan Guarantee Board (ELGB), whose purpose was to provide guaranteed loan assistance to major corporations whose failure could have a material adverse impact on the economy. Lockheed, which was having difficulty selling its aircraft, applied for assistance. When its offers of bribes were uncovered,

the ELGB and U.S. Treasury Department, and the Senate Banking Committee, which provided oversight, became infuriated, due to concerns that the company had used part of the assistance it had received from American taxpayers to bribe foreign government officials. The Senate banking committee chairman William Proxmire conveyed this anger in a letter sent to Secretary of Treasury William Simon.

“In my view,” he wrote, “the single most effective method for bringing these practices to a halt would be to disclose the names of the foreign officials who received the payments from Lockheed and the names of the so-called marketing consultants or agents who made these payments on behalf of Lockheed. The very fact that these names were disclosed would serve as a powerful deterrent in discouraging future demands for pay-offs on the part of foreign officials doing business with U.S. corporations.”

Naturally, these foreigners included former Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka and Yoshio Kodama. In his reply to Proxmire, Secretary Simon wrote: “Lockheed’s financial condition is significantly weaker and its cash position significantly more vulnerable than the other corporations to which you allude in your letter…the release of the information you have requested could cause the failure of the company with all its attendants injuries and dislocations.”

FORMER WAR CRIMINAL AN AGENT FOR BRIBERY

Upon learning that the U.S. government has become aware of its overseas bribes, Lockheed officials turned pale. In late August 1975, immediately after ELGB’s staff visited Lockheed’s headquarters in California to review the bribery situation, Lockheed’s vice president and treasurer committed suicide.

At that time however, the U.S. government was torn over whether or not to make public the names of the foreign officials, and the Church committee had also focused its attention on bribery cases that took place in Europe and the Middle East. According to Blum, in November 1975, the situation changed rapidly around the time he traveled to Europe. Earlier that month, Blum had visited West Germany and the Netherlands to investigate the bribes paid by Lockheed, and during his trip he was informed by a colleague of something that left him highly astounded.

“During my trip to Germany, I was told that really important payoff was in Japan. Before that, nobody understood what those documents were, because many of them were written in Japanese. The Congressional Research Service translated them into English, and our staff were astonished. The first discovery was that the middleman was former war criminal, Yoshio Kodama. We did research at the Library of Congress and went to the National Archives to have record of the Tokyo International Military Tribunal and people who investigated him. That was really astonishing. An American corporation hired a former war criminal and bribed the Prime Minister of a major country, an important U.S. ally. And Kodama had ties with the yakuza and was involved with so many dirty things across the board. How did this guy get into the Japanese political structure? But until then, nobody, including ruling party politicians, questioned it.”

While it may be difficult to imagine today, it can be said that in the postwar history of Japan, Yoshio Kodama led a rather bizarre existence. In his youth, Kodama was no more than a young and aggressive ultranationalist. His name first popped up during the war, when he organized the Kodama Agency in Shanghai at the request of the Japanese Imperial Navy. His ostensible function was procurement of materials for the Japanese war effort, but he was essentially looting assets from Chinese

Soon after the war’s end, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers designated Kodama a Class A war criminal and ordered his arrest. He was incarcerated in Sugamo Prison. After his release, he used some of the huge assets he had brought back from China to donate money for the founding of the Liberal Party, the predecessor of today’s Liberal Democratic Party.

Afterwards, Kodama became known as a fixer, not only in the realm of politics, with the latent power to influence rightist groups, underground criminal syndicates and corporate racketeers. The source of his power was his capability to intimidate people. Kodama set up errant individuals based on information he’d obtained from underworld, and sometimes entrusted rightists or Yakuza to attack them, thereby keeping himself insulated from the long arm of the law.

Kodama, however, failed to intimidate the U.S. Senate committee. If it had been the Japanese Diet, hinting at trouble would have been enough to cause politicians to tremble in fear and call for a halt to investigations. But the Church committee and its investigative staff, who were mostly in their 20s to their early 30s, smoldered with youthful idealism. They did not seem the least bit intimidated by the dark curtain of Japan’s rightists.

THE DEBATE THAT CHANGED JAPAN’S HISTORY

At that time, had the Church committee known that Tanaka, the former prime minister, had been included among the bribe recipients? With a vigorous nod of his head, Blum continued.

“We discovered a number of things in the countries that were investigated, but important point was that there was nothing of the magnitude of Japan. It was a payoff to the highest level of the Japanese government, not a third-world country.”

Lockheed, however didn’t just stand by and watch. It knew that if the investigation were to proceed, sooner or later the publicizing of the names of foreign government officials might deal the company a mortal blow. So it sought out cooperation of a major figure in the Ford Administration — Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger.

On November 19, 1975, Lockheed’s legal counsel Rogers & Wells sent a letter to Kissinger warning against unfairly maligning friendly foreign leaders and governments that were on the receiving end of the bribes.

The letter read, in part: “…due to the extreme sensitivity of some of the information involved, Lockheed would prefer at least initially to describe orally some of the documents should you or any representative you may designate desire to verify the seriousness of the problem.”

Nine days later, Secretary Kissinger wrote to the U.S. Attorney General, warning against making public of committee findings as disclosure of names of foreign officials might have grave consequences for foreign relations.

As Jack Blum recalled to me, “I was not in that meeting, but Lockheed’s legal team, Rogers & Wells attorneys, came to see Church, asking him to limit the investigation to the Middle East.”

Up to that point, it is clear that the investigation had revealed bribery by Northrop to sell its planes in the Middle East, where officials received enormous commissions through transactions with international arms dealers. For Lockheed to also have been involved seemed nothing out of the ordinary. How then did the Church committee respond to the requests to protect high-ranking officials in Japan or Europe who had been involved in certain types of deals?

“Frankly speaking,” Blum continued, “we had division of opinion at that time. I think Jerry Levinson, the committee’s chief counsel, wanted to go along with Rogers & Wells. But I said we can’t do that, because we had too much evidence, such as receipts with the codename Peanuts. It was too important to overlook. I debated with Levinson and Church backed me up and said, ‘Let’s go.'”

If Jack Blum had lost that debate, one can only wonder how things might have turned out when revelations of the Lockheed scandal that was to lead to Tanaka’s arrest came to light the following February. Without any mention of Tanaka, Kodama and Marubeni, the incident might very well have attracted little attention. So in a very real sense, the debate that took place in a room of the U.S. Senate office building in the winter of 1975 can be said to have changed Japan’s history.

Church’s military service record in the archives at Boise State University, may suggest a surprising reason why Church decided to along to go along with Blum’s argument. As a young U.S. Army intelligence officer, Church at the end of World War II had been posted in Shanghai, Yoshio Kodama’s old stomping grounds. In letters that Church wrote home to his family, he raised questions over the tragic conditions of the Chinese, Western colonialism and American companies that operated in Asia.

While it is unlikely Church and Kodama ever encountered one another at that time, it may be said that in a sense the roots of the Lockheed scandal date began in the late stages of the war in China. Kodama, who became the fixer representing Lockheed, had acquired huge wealth from his illegitimate wartime activities in China. And Frank Church, a liberal politician, was critical of multinational corporations. It was an irony of fate that the lives of the two, which took completely different directions after the war, crossed paths in the Lockheed scandal.

NO RELEASE FOR HIS PENT-UP ANGER

Then how did Kakuei Tanaka, who was the first Prime Minster to be arrested, view the scandal? The relationship between Lockheed and Kodama extended back to the late 1950s, when Japan’s Defense Agency (currently the Ministry of Defense) began its F-X program for procurement of jet fighter aircraft. This murky process led to the involvement of influential members of the Liberal Democratic Party, even prime ministers.

Two other anecdotes can be found relating to this matter. One was the memoirs (titled “Netsujo” or “Passion”) of Kazuko Tsuji, a geisha and Tanaka’s mistress who was based in the Kagurazaka district of Tokyo. Tsuji related that after the Lockheed incident became public, Tanaka had told her, “There’s no precedent of a prime minister being arrested.”

Tsuji wrote: “It appeared Tanaka believed there was no chance he’d be arrested although Takeo Miki, who was a member of the same party but who abided by a different political creed, was head of the government. Previously a Minister of Justice had exercised directional authority to avoid arrest of Eisaku Sato, who while serving as Secretary-General of the Liberal Party had been on the verge of being arrested for his alleged involvement in a bribery scandal involving the shipbuilding industry. From this, Tanaka was confident there was no chance a prime minister would be arrested, and didn’t take it seriously.”

The shipbuilding bribery scandal occurred soon after the war, during the government under Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, when members of the ruling Liberal party allegedly accepted bribes from shipbuilding and ocean freight transport companies. When the prosecutor began an investigation, Justice Minister Takeru Inukai intervened and the full truth never came to light.

The second item concerns a memorandum of conversation with Nixon’s then-National Security Adviser, Henry A. Kissinger, who on June 12, 1972 was visiting Japan. This was at the time when Tanaka’s political rival Takeo Fukuda was engaged in an intense battle over who would succeed Prime Minister Eisaku Sato. According to the declassified U.S. document Tanaka had asserted, “I first started my political activities under Prime Minister Shidehara, who was one of the disciples of the late Prime Minister Yoshida. Since then I have remained a good student of the Yoshida school of political training.”

When reading this file, at first glance I felt skeptical, wondering why it was that Tanaka had stressed such personal background. But according to people in politics and finance who had dealings with Tanaka however, it was a phrase he liked to use.

Yoshida and elite politicians under Yoshida’s tutelage, referred to collectively as the “Yoshida school,” developed into the mainstream conservative force that dominated Japan’s politics in the postwar era. These bureaucratic and financial circles, along with powerful family connections, formed the establishment to which Tanaka, who was born and raised an impoverished farmer in snow-covered Niigata prefecture, managed to ascend to the pinnacle.

At that time, Tanaka harbored confidence that he was welcomed as a member of the mainstream conservative establishment, and naturally felt insulated from the judiciary. As it turned out, he was beset by a mixture of anger, sadness and humiliation at what he saw as betrayal, and conveyed so to his mistress soon after being released on bail.

In “Passion” Tsuji wrote, “I knelt on the tatami mat and looked up to his face. Recalling that moment, from his expression the words, ‘There’s no way for him to release that pent-up anger’ occurred to me.

“I thought surely, for him to experience the humiliation to which no previous prime minister had ever been subjected must have been mortifying. I never felt sorrier for him than at that moment.”

The flashpoint in Washington that ignited the Lockheed scandal not only exposed the sleazy machinations of Yoshio Kodama and the crimes by multinational corporations and a prime minister; it also revealed the corruption that was rampant the mainstream conservative establishment that had ruled Japan since the end of the war. As such, the Lockheed incident must surely rank as the greatest scandal of the postwar era.