Luke Fowler is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Administration and MPA Director in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. He completed his Ph.D. at Mississippi State University in 2013. His research interests include policy implementation, energy and environmental policy, state and local government, public management, public budgeting and finance, and organizational theory. He has written articles for American Review of Public Administration, Review of Policy Research, State and Local Government Review, Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting, & Financial Management, Environmental Politics, Social Science Journal, and Electricity Journal. He has also presented papers at numerous conferences including the annual meetings of the Southeastern Conference on Public Administration and American Association of Public Administration.

Bryant Jones has worked in the federal government on environment, energy, and public diplomacy issues at the White House and the Department of State. He is a Public Administration doctoral student in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. Additionally, he is National Security Fellow at the Truman National Security Project. His research interests include inter-organizational management and relations as well as environment, energy, and national security policy.

Air Quality Awareness Week (April 30 to May 4, 2018) is an outreach program sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and its AirNOW partners, which include the National Weather Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Department of State, to promote awareness of air quality issues, including their impacts on human health. Air Quality Awareness Week is well-timed as warmer temperatures mark the beginning of a new summer season full of auto-travel, outdoor activities, and wildfires, which will inevitably lead to greater exposure of Americans to harmful air pollutants.

Although it may seem mundane to some, air quality is still a major environmental issue in the United States and abroad. This is particularly true for California and the Rust Belt states, where emissions from cars and industry have caused some cities to become among the most polluted in America. However, geography and weather in Western states also contribute to poor air quality, where wildfires and inversions increase particle pollution and worsen bad air days.

This year’s theme is Air Quality Where You Are, which is meant to inspire people to take steps in their local areas to reduce air pollution. While the Clean Air Act (CAA) is generally considered to be successful, millions of Americans are still exposed to air pollutants in their communities each year. As such, it is a good time to consider air quality where we are, and what local governments are doing to improve it.

A LITTLE BACKGROUND

The CAA is the backbone of air quality policy in the United States. Although EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt has worked to undermine the CAA over the last year, it is still estimated that between 1990 and 2020 the CAA will have prevented over 230,000 early adult deaths, 280 infant deaths, 200,000 cases of heart disease, 120,000 emergency room visits, 5,400,000 lost schools days, and 17,000,000 lost work days. Cumulatively, these reductions in health costs will also create $2 trillion in economic benefits, compared to $85 billion spent on CAA programs.

However, these benefits have not been equally distributed across the country, and local governments are key forces in creating local outcomes from state and federal programs. Starting with the original 1970 legislation and further solidified by the 1977 and 1990 amendments, the CAA relies on a federal-state partnership; for example, the EPA sets the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) while states develop State Implementation Plans (SIPs) to implement those standards. As the key environmental policy challenge is balancing environmental and health costs against economic benefits, this system purposely devolves decision-making to the level closest to those affected by the consequences of that balancing act. This has provided states significant discretion in developing their own policies, organizing resources, and shaping the role of local governments. Although 24 states have no local air agencies, the other 26 states have local air agencies that function as hidden partners in air quality management. These local agencies bring with them important knowledge and expertise concerning the political, socio-economic, and technical challenges of managing local air quality.

This begs two questions. First, what are local governments doing? And, second, have their efforts improved local air quality? To examine these questions, we surveyed managers of the 118 local agency members of the National Association of Clean Air Agencies (NACAA). Depending on the survey item, we received between 77 and 79 responses, making for response rates of between 65.3% and 66.9%.

WHAT ARE LOCAL GOVERNMENTS DOING?

To determine what local governments are doing, let’s look at three issues: the authority local governments have over air quality, the policy initiatives these governments are using, and who these local governments are working with.

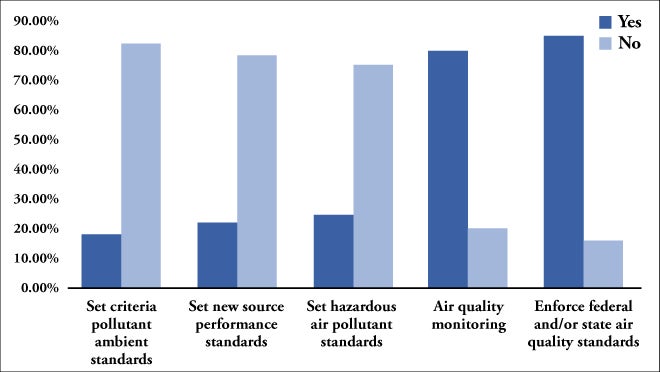

Figure 1. What Authorities Do Local Air Agencies Have?

Figure 1 above shows local air agencies are far more likely to be involved in monitoring and enforcement activities than in setting standards. Notably, the distinction between these two classes of authorities is that monitoring and enforcement are administrative tasks, while setting standards are political tasks. On the one hand, this allows local implementation capacity to be leveraged in enforcing federal and/or state standards and in monitoring local pollution. Local air agencies likely have a better understanding of local challenges to implementing policies and the sources of local air pollution than state agencies. On the other hand, local air agencies lack the authority to balance local values of environmental and health costs against economic benefits when determining air quality standards. This means that political decisions are still retained at the state-level and are not specifically adapted to local concerns.

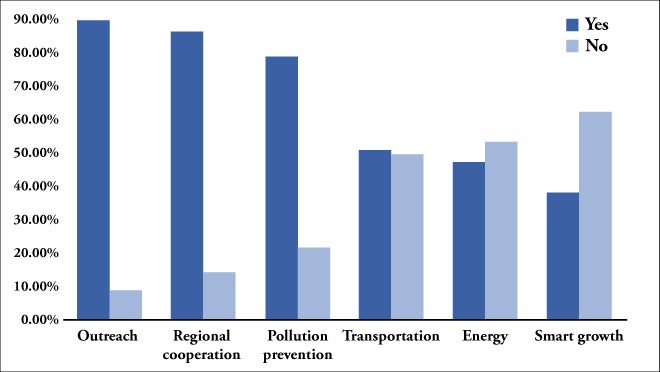

Figure 2. What Policy Initiatives Are They Using?

How then do these local governments go about managing air quality? Figure 2 shows conventional tools for managing air quality are the most common form of local initiatives. These include outreach (i.e., campaigns and outreach programs to educate the public on air quality issues), regional cooperation (i.e., partnerships with other organizations to reach a wider target population), and pollution prevention (i.e., programs addressing air emissions before they happen). On the other hand, more innovative tools for planning and developing urban landscapes to reduce emissions are less common, though still prevalent among local air agencies. These include transportation (i.e., adopting new technologies or strategies to reduce mobile source emissions), energy (i.e., adopting new technologies or strategies for energy efficiency and alternative fuels), and smart growth (i.e., planning and development with sustainability and the environment as a focal point).

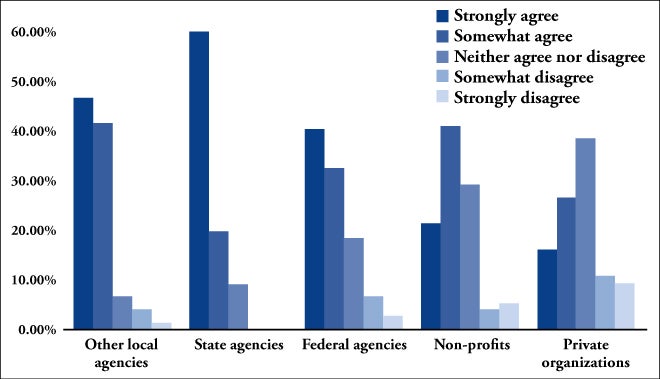

Figure 3. Who Are They Working With?

Much of the work these local governments do is cooperative in nature. To determine who local air agencies are working with and how well they are working with them, we asked respondents to rate their level of agreement with the following statement: my office actively cooperates or partners with [type of agency] working on air quality issues in my area. In general, Figure 3 shows that respondents are more likely to agree than disagree that they have cooperative relationships with other organizations working on air quality in their areas. However, these relationships seem to be focused on other governmental agencies, which is not surprising given the nature of air quality as a public good and the structure of the CAA that places legal obligations on state and federal agencies. On the other hand, respondents are less in agreement that they have cooperative relationships with non-profits or private organizations.

HAS THIS IMPROVED LOCAL AIR QUALITY?

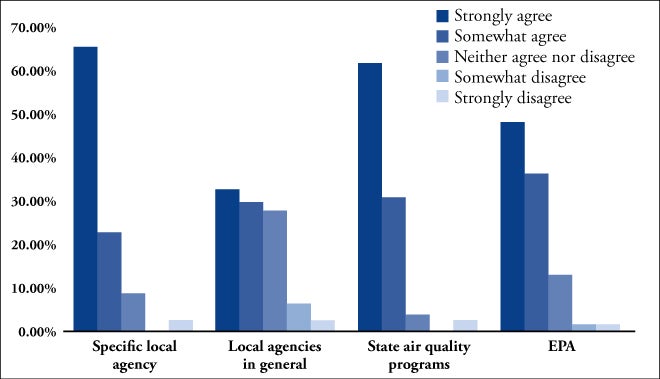

Taken as a whole, this survey data suggests that local air agencies are engrained in air quality management, but there are limitations to their capacity and activities. Given this, it merits asking whether and how effective these local government efforts have been when it comes to improving air quality. To determine this, we first consider what our survey respondents think. Specifically, we asked respondents to rate their level of agreement with the following statement: [type of agency] has a direct impact on air quality in my area. Figure 4 shows how much local managers agreed that specific agencies had a direct impact on air quality in their area. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of respondents agreed that their specific local agency had a direct impact on air quality in their area. More interestingly, though, respondents rated the impact of their local agency comparable to that of state air quality programs and the EPA. In other words, local air managers believe their agencies are just as important in managing air quality as state and federal agencies. On the other hand, while local air managers believe their agencies are important in managing air quality, they are less confident in the capacity of other local agencies to manage air quality.

Figure 4. Perceptions of Impact on Air Quality

Although these perceptions may seem counterintuitive, they largely align with our extensive research of these issues over the last two years. In general, our research indicates that when local governments are involved, air quality tends to be better. However, this is highly dependent on their jurisdictional sizes, partnerships, authorities, and policy initiatives. In most cases, larger municipalities have the capacity to unilaterally impact air quality over a regional area, while smaller cities are limited in their ability to create similar impacts. For smaller cities, cooperation with other governmental and non-governmental organizations is necessary to expand scopes of operations. Additionally, local governments are also constrained by their authorities to set air quality standards and ability to use policy to alter economic behavior. As such, local governments with more authorities and more diverse policy tools are also more effective in improving local air quality outcomes. Consequently, there are specific local air agencies that have drastically improved air quality in their areas, but others have fallen short.

AN OPPORTUNITY TO REFLECT

Air Quality Awareness Week is meant to be a time for us to reflect on air quality where we are and how it impacts our quality of life. As such, we need to think long and hard about what our governmental institutions are doing to improve it. Certainly, there have been many successes since the original CAA was passed in 1970 and since the latest amendments were passed in 1990. However, there is always progress to be made, especially when there are drastic inequalities across the country.

Although they may seem to be hidden partners, many local air agencies are taking on important administrative roles in making CAA programs work at the local level, through monitoring and enforcement, outreach programs, pollution prevention, and cooperative relationships with other government agencies. Other local air agencies are taking on even more responsibility by also setting air standards, creating policies to improve transportation and energy infrastructure, developing smart growth plans, and pursuing cooperative relationships with non-profit and private organizations. As such, there are plenty of examples of successful local air quality programs. However, while specific local agencies are making important impacts in their areas, not all are doing so and there are limitations to how effective local agencies can be in improving air quality.

Though they possess the potential for great effectiveness, creating local air agencies is not necessarily a silver bullet for reducing air pollution. Finding new ways to increase local involvement might be a key first step though, since local leaders tend to have a good understanding of the unique circumstances that contribute to problems in their areas. While we consider the air quality where we are this week, we should also consider the local agencies where we are and what they are doing to improve our air quality.