John Freemuth is Professor of Public Policy and Executive Director of the Andrus Center for Public Policy at Boise State University. His primary academic interest is with the public lands of the United States. Currently his work gravitates towards puzzling out the relationship between science and public policy as it relates to issues surrounding the public lands. He wrote “Thoughts on the Role of Science in Public Policy Making” in Ecology and Conservation of Greater Sage-Grouse: A Landscape Species and Its Habitats (University of California Press, 2011). He just published his and Zachary Smith’s Environmental Politics and Policy in the West (UC Boulder). He chaired the Science Advisory Board of the Bureau of Land Management, after being appointed by Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt. He was the Senior Fellow at the Cecil Andrus Center for Public Policy from 1998-2011, becoming Executive Director of the Center in July, 2016.

Mackenzie Case is a GIS and Policy Analyst at Boise State University. She will receive a Master of Public Administration with an Emphasis in Environmental, Natural Resource and Energy Policy and Administration in May 2017 and will pursue a PhD in Public Policy and Administration with an Emphasis in Environmental Policy and Administration starting in Fall 2017 at Boise State University. She also serves as the Student Congress Representative on the Public Lands Foundation Board of Directors and has previous professional experience in conservation nonprofits and fundraising. She received a BA in Politics at Cornell College.

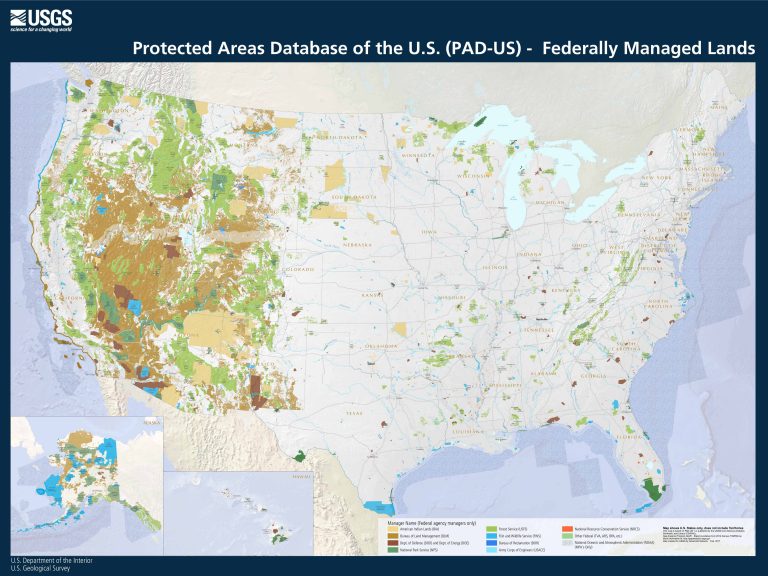

Our federal public lands are breathtaking in their ecological scope, in their bountiful natural resources, and in their policy complexity. The history of how we arrived at current policy arrangements is also long and convoluted. According to the Congressional Research Service, today the four major federal land agencies manage about 27% percent the United States’ land mass, much of which is concentrated in the west. The U.S. Forest Service manages about 193 million acres, the National Park Service about 80 million acres, the Fish and Wildlife Service 89 million acres, and the Bureau of Land Management 248 million acres.

Americans have had a long conversation about the purpose of the federal estate. Yet, the seizure of Malheur National Wildlife Refuge buildings in southeastern Oregon by armed and self-appointed “constitutionalists” was outside that conversation to many people. It was viewed as a dangerous escalation in a long, admittedly passionate but rarely violent, discussion of federal or public land management in the western United States. The Malheur event prompted many non-westerners to ask who the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) was and why they manage so much land. It also brought to the forefront many questions from those unfamiliar with western land issues, the history of the federal lands, or public land management policies.

THE HISTORY OF U.S. LAND POLICY

Government management of public land predates the country itself, as both the British and American colonists regulated logging to preserve supplies of timber for building naval vessels. After the Revolutionary War, the new country quickly sought both to acquire more land (the “Acquisition phase”) and to ensure private sector ownership (the “Disposal phase”). Acquisition was accomplished by war or purchase, while Disposal was done to raise cash and promote new settlement. The indigenous inhabitants of these lands were also removed, usually by force.

In the 1860s a new policy of “Retention” developed, primarily in the west, and is best understood through Yellowstone National Park’s designation as not just the first national park in the U.S. but also the world. Other parks would follow, though in an ad hoc and piecemeal fashion. The National Park Service was created in 1916 to manage and conserve these parks and provide “enjoyment for future generations.” Other lands fell under the Retention policy, as well.

By the 1880s, there were growing concerns over deforestation. This led Congress to give the President the power to create forest reserves. Later renamed national forests, they were placed under the administration of the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), which was created in 1905. Congress later revoked that power, but did create eastern national forests though land purchases under the Weeks Act. The charismatic Gifford Pinchot, first Chief of USFS, helped make the USFS the first professional land management agency in the U.S. Pinchot and others made it clear that the forests were to be managed for the production of resources for citizens’ benefit. Thus, the Retention policy evolved into an era of Federal Land Management with a utilitarian philosophy: forests should be managed for the “greatest good for the greatest number” in the long run.

President Theodore Roosevelt used executive authority to create early national wildlife refuges, including Malheur; other presidents would follow his lead, as would Congress. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (created in 1940 after many earlier configurations) now manages these early reserves and those established later. These lands were set aside specifically for preservation of land for wildlife and habitat, though other uses could be allowed.

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) was created in 1946 by merging the General Land Office and the Grazing Service, which was originally set up to manage grazing. The Grazing Service originated in the 1930s with the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 to bring stability to western grazing and to help reduce overgrazing. One key phrase of that act stated:”That in order to promote the highest use of the public lands pending its final disposal, the Secretary of the Interior is authorized, in his discretion, by order to establish grazing districts.” Before the Taylor Grazing Act, federal officials, including Secretary of Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur and President Hoover, offered to transfer the pre-BLM public lands (the public domain lands) to the states to manage, minus the sub-surface mineral estate. The states declined, citing the poor condition of the surface estate. The word “disposal” led some to conclude that eventually these lands would be transferred to the states to manage or perhaps be sold.

Western congressional representatives closely watched and in a sense supervised the BLM through the 1960s. Leading scholars such as Phillip O. Foss referred to this as a “private government,” and suggested the agency was “captured” by the interests it was supposed to regulate. To state it differently, the agency conformed to the desires of Congress’ ranching and mining constituencies. The BLM was often referred to as the “Bureau of Livestock and Mining” as those were the primary uses and users of these lands. BLM employees came from (and still often come from) smaller western towns and ranching backgrounds. They were primarily trained at western land grant universities, reinforcing the tradition of placing a priority on using federal lands for their natural resources. BLM lands are located almost exclusively in the west and BLM manages most federal lands because this was the land not already set aside as national forests or national parks and monuments. Some in the west still believed that the BLM lands would be “disposed” of in some manner – that is, transferred from federal to state ownership or perhaps sold.

This notion changed with the passage of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA). This act superseded the Taylor Grazing Act and made it national policy that the BLM lands would be retained in federal ownership, thus making this an example of Retention policy. Retention, and new environmental laws and public interest in the BLM lands for recreation, wildlife, wilderness and so on, helped set off the Sagebrush Rebellion of the late 1970s. There had been previous protests dating back to creation of the forest reserves, but this rebellion is well remembered. Ronald Reagan’s election helped defuse the movement, as his Secretary of Interior James Watt pushed for the restoration of natural resource use and the weakening of environmental regulations.

Today, the BLM manages much of its land for the use of resources, as does the USFS. These agencies are considered multiple-use in that preservation is part of their activities. In contrast, the National Park Service and US Fish and Wildlife Service have preservation as their dominant mission. Many residents in small rural western towns believe traditional uses and users of BLM lands are diminishing and over-regulated. Additionally, many Native Americans take issue with the notion that ranchers and others were here “first,” a refrain sung by the Malheur occupiers. Agencies can therefor struggle to determine the balance between use of natural resources and protection of these lands. It has often been said that the real challenge is to manage multiple users, rather than uses.

There has been an off-again on-again movement to transfer much of the federal lands apart from the national parks and wilderness (a land designation made by Congress) to states management. However, the cost of managing these lands, including the massive financial consequences of wildfire, and uncertainties over how the land could be used, continue to render this politically unpalatable to many.

PUBLIC LAND CHALLENGES IN THE AGE OF TRUMP

New Secretary of Interior Ryan Zinke takes office in this complicated political, historical, and cultural context. He described himself as a fan of Theodore Roosevelt, often considered one of America’s most pro-conservation presidents. Sportsmen’s organizations reportedly sought a nominee who was a hunter or fisherman and opposed proposals from some Republicans to sell off or transfer millions of acres of public land, and Zinke fit these criteria. As stated as his first day on the job, “I cherish our public lands. I have absolutely and unequivocally opposed any attempts to transfer, sell, or privatize our public lands, and serving as their top steward is not a job I take lightly.”

Although some conservation groups are cautiously optimistic that they can work with Zinke, others are worried about his support for fossil fuel production on public lands and his position on other key environmental issues. One of his first actions, perhaps aimed at pleasing sportsman groups, revoked a ban of lead bullets on federal lands; the ban having come right at the end of the Obama Administration. Consistent with the Trump Administration’s focus on “energy independence”, he thus far seems to support increased domestic oil and gas development. On federal lands, oil and gas development indeed remains legitimate use of multiple use federal land. However, given controversy over potential impacts to wildlife, recreation, and other uses of public land, the main challenge facing Zinke and public land agencies may be where that development should occur rather than should simply whether they should occur. Additionally, while Zinke has addressed tribal sovereignty as a priority issue, conflicts such as the now approved Dakota Access pipeline may predict further conflicts with how Native American concerns are addressed on federal lands.

Trump’s election has also lent new energy to cyclical calls for transferring federal public lands to state control. This controversy is more than a century old and deeply rooted in western history.

Zinke has sent mixed signals on this question. He resigned as a delegate to the 2016 Republican National Convention over disagreement with a GOP platform plank that supported public land transfers. However, he has also been criticized during his Congressional tenure for supporting a rules package that included language viewed as a step toward public land transfers. Trump also opposed federal land transfers early in 2016, but sportsmen and others are worried about whether he will stick to that position. Perhaps he will follow the path of someone like former Reagan-era Secretary of the Interior James Watt, who placated Sagebrush Rebels by changing regulations and supporting traditional multiple use activities. Ironically it was Congress who blocked the implementation of BLM’s new “2.0” planning regulations under the Congressional Review Act which then defaults to 1983 regulations; regulations that are outdated to many. Zinke’s opinion on the issue remains unclear, as does whether or not he will attempt to persuade Trump not to sign the bill blocking the implementation of the regulations.

Although Zinke’s commitment to federal land ownership may be heavily watched by conservation groups and sportsmen groups, it is important to note that any federal land transfers would require also require Congressional approval. Senate Democrats hold enough seats to filibuster such measures. Moreover, the case for land transfers is based on a specious argument that states can do a better job at managing public lands. This claim never answers the question of “better job at what?” while members of Congress pushing the concept already face heavy pushback from significant numbers of their constituents and the public. Despite backlash, however, some members of Congress seem to be prioritizing major changes in how federal lands are managed, including the designation of National Monuments.

Unsurprisingly, another major concern is that the Trump Administration may try to reverse some of President Obama’s national monument designations, including the recent Bears Ears National Monument in Utah. Historically, some individual monument proclamations – which presidents can make unilaterally – have been opposed by states and adjoining communities. However, it would be unprecedented for the Trump administration to try to reverse designations by President Obama. According to a Congressional Research Service analysis, the Antiquities Act does not include language authorizing repeal of proclamations, although boundaries defined in Antiquities Act designations may be slightly altered. However, the issue has never been litigated and Zinke’s opinion on the issue is also unclear. In his confirmation hearing, he suggested that Trump may consider attempting to revoke Bears Ears, but also that he would consult with local politicians and residents before making recommendations to President Trump.

In addition to these challenges, Secretary Zinke has yet to see his leadership team confirmed and put into place. Agency heads can be either political appointees or career civil service employees, though the civil service appointees serve at the pleasure of the president and would return to a different position if required. Agency heads are overseen by political appointees at levels just below the secretary. The people who fill these positions, and the organizations that influence those selections, will affect the department’s direction as much as Zinke will.

There is evidence that careerists in agencies understand that political appointees have agendas. The question then becomes whether the appointees try to work with or against the professionals in the agencies. Working with professionals, including scientists and other experts, appears to work better than the alternative. Moreover, this is not a partisan issue, as pointed out by former Secretary Jewell at a farewell speech to Department of Interior employees on the Boise State campus, where she emphasized listening to professionals, including scientists. There is some indication that Zinke wants to decentralize Interior pushing more decisions out to field level decision makers, but specifics are unclear.

Finally, many agency professionals may be fearful of budget cuts under the Trump Administration. Zinke himself expressed dissatisfaction with the White House’s proposal, which proposes cutting the Interior’s budget by 12%. Underfunded programs within the Interior could decrease morale for Interior professionals, as well as make any sweeping changes difficult to implement.

CONCLUSION

Secretary Zinke must also react to staffing and budgeting challenges, as well as Republicans in Congress who see the Trump Administration as a chance to push controversial agendas including public land transfers and challenging the Antiquities Act. In addition to political and administrative challenges, he will also have to contend with the often competing pressures from the public and interest groups, as well as external factors such as climate change (an issue that some members of Trump cabinet infamously refute). While Zinke strongly maintains that he shares the ideals of Teddy Roosevelt, balancing different uses on public lands such as conservation and resource extraction, would be a challenge for any incoming Secretary.