Stephen F. Knott is a Professor of National Security Affairs at the United States Naval War College. He served as co-chair of the University of Virginia’s Presidential Oral History Program and directed the Ronald Reagan Oral History Project. Professor Knott received his PhD in Political Science from Boston College, and has taught at the United States Air Force Academy and the University of Virginia. His most recent book, Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, was co-authored with Tony Williams and published in September, 2015.

The presidency of John F. Kennedy was arguably the high water mark of 20th century American progressivism. While one could argue that this honor belongs to Franklin Roosevelt, the rise of television allowed President Kennedy to forge a bond with the public that was far greater than he otherwise might have made in his two years, ten months, and two days in office. As a result of his mastery of television, the abbreviated Kennedy presidency became the benchmark by which many progressive politicians and scholars measure presidential success.

John F. Kennedy is the epitome of the visionary president promoted by Woodrow Wilson and other avatars of 20th century American progressivism. Kennedy’s charisma allowed him to form the type of bond that Woodrow Wilson and other progressive thinkers considered to be the critical element of effective popular leadership. Determined to liberate the American government from the constraints of the Constitution’s antiquated checks and balances, Wilson believed that the president (assisted by the best and the brightest administrators) was to serve as a visionary and lead the nation, in Kennedy’s case, into the “New Frontier.” Wilson’s expansive, one might even say boundless conception of presidential power was endorsed by many mid-twentieth historians and political scientists, some of whom were linked to the New Frontier, including Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Richard Neustadt, Henry Steele Commager, and James MacGregor Burns. All were advocates, in various forms, of the idea of “presidential government.”

JFK’S VIEW OF THE PRESIDENCY

In addition, Knott will discuss his new book on George Washington and Alexander Hamilton at 7 p.m. on Thursday, April 6 in the Boise State Education Building. He will also sign copies of his hew book, Washington & Hamilton: The Alliance That Forged America on Friday, April 7 from 7 – 8 p.m. at Rediscovered Books.

Dr. Stephen F. Knott will be on the campus of Boise State University on Friday, April 7 from noon – 1 p.m. presenting on the same topic as this article.

In addition, Knott will discuss his new book on George Washington and Alexander Hamilton at 7 p.m. on Thursday, April 6 in the Boise State Education Building. He will also sign copies of his hew book, Washington & Hamilton: The Alliance That Forged America on Friday, April 7 from 7 – 8 p.m. at Rediscovered Books.

Click here for information about all three events .

In a January, 1960, speech at the National Press Club, Kennedy argued that the central issue of the 1960 campaign was “not the farm problem or defense or India. It is the presidency itself.” The history of the United States was in fact the history of the presidency: “the history of this Nation – its brightest and its bleakest pages – has been written largely in terms of the different views our Presidents have had of the Presidency itself.” Not since Woodrow Wilson’s time had “any candidate spoken on the presidency itself,” and Kennedy hoped that the proper scope of executive power would be the central focus of the election of 1960. Dwight Eisenhower’s stodgy Rotary Club presidency was simply not suited for the challenges of the “revolutionary” 1960s – what was needed was a reinvigorated Wilsonian presidency to replace Ike’s “detached, limited concept of the Presidency.”

The presidency demanded, in Kennedy’s view, “a man capable of acting as the commander in chief of the Great Alliance” who would not concern himself with constitutional niceties, for he “must be prepared to exercise the fullest powers of his office – all that are specified and some that are not.” And he must fulfill Woodrow Wilson’s vision of a president serving as “educator-in chief, by “reopen[ing] channels of communication between the world of thought and the seat of power.” The chief executive must also be something of the nation’s preacher-in-chief, for the presidency “must be the center of moral leadership.” Kennedy’s seemingly infinite vision of presidential power was matched by his unbridled optimism in human potential. He would note in 1963 that “man can be as big as he wants. No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings.”

Dwight Eisenhower’s constricted view of presidential power was inappropriate for the central role “the Presidency was meant to have in American life,” Kennedy claimed. Foreshadowing the great issue that would dominate and divide the nation in the 1960s, Kennedy noted that the proper conception of presidential power including extinguishing a “brushfire [that] threatens some part of the globe – he alone can act, without waiting for the Congress.” The founding fathers drafted a “Constitution [that] envisioned: a Chief Executive who is the vital center of action in our whole scheme of Government.” Kennedy’s beau ideal of a president was one who embraced the idea that “upon him alone converge all the needs and aspirations of all parts of the country, all departments of the Government, all nations of the world.”

JFK IN THE WHITE HOUSE

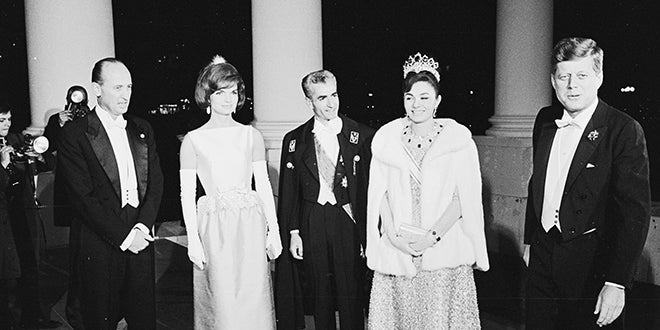

In his inaugural address, Kennedy committed the United States to paying “any price, bear[ing] any burden, meet[ing] any hardship, support[ing] any friend, oppos[ing] any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty. This much we pledge – and more.” He also called for an international effort to “explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths and encourage the arts and commerce” and appealed for “a struggle against the common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself.”

Kennedy’s presidential management style went well beyond Woodrow Wilson’s notion of centralizing federal power in the executive branch. For Kennedy, centralizing power meant centralizing it in the Oval Office itself. Kennedy was not only impatient with separation of powers, he viewed his own Cabinet, and the federal bureaucracy writ large, as an impediment to progress as well. Determined to be his own Secretary of State, Kennedy slighted his choice to head that department, Dean Rusk, whose selection was based in part on his deferential manner. Kennedy’s speechwriter Theodore Sorensen would later write with glee that “no decisions of importance were made at Kennedy’s Cabinet meetings and few subjects of importance, particularly in foreign affairs, were ever seriously discussed.” Sorensen also boasted of the fact that “not one staff meeting was ever held, with or without the President” adding that Kennedy “paid little attention to organization charts and chains of command which diluted his authority.” Kennedy, in fact, had no chief of staff, and believed that he was capable of playing that role. There would be no Sherman Adams in the Kennedy White House, since, in JFK’s view, Adams typified Eisenhower’s propensity for importing stultifying military practices into the more free-wheeling world of politics and government.

From the first day of his presidency, Sorensen claimed, Kennedy “abandoned the notion of a collective, institutionalized presidency.” In other words, presidential government under Kennedy was the personification of micromanagement from the Oval Office. This was policymaking by the select few, by the band of brothers. This was a presidency that put a premium on action, or more accurately stylish action, and woe to those like Rusk or Chester Bowles who lacked that style and were noted for their unattractive propensity for deliberation. The fleeting Kennedy presidency, the first television presidency, was from the beginning to its tragic end a media event. Kennedy was made for television, and his bronzed appearance in four televised debates had helped him defeat a sweaty, shifty-eyed, and ghostly Richard Nixon. As historian Alan Brinkley has noted, Kennedy was “a witty and articulate speaker, [who] seemed built for the age of television. To watch him on film today is to be struck by the power of his presence.”

The shock of the Kennedy assassination for those Americans who were alive in 1963 was rivaled only by the events of December 7, 1941, or later by September 11, 2001. The poignant images of the thirty-four-year-old First Lady kissing the President’s casket and his three-year-old son saluting the same were almost too much to bear. When the news broke from Dallas, the nation’s three television networks suspended their normal broadcasting schedule for the first time in their short history to focus non-stop on the funeral of the President, followed shortly by the murder of his assassin. After Kennedy’s death, 65 percent of the American public claimed they voted for him, although he had only received 49.7 percent of the popular vote.

THE MYTH OF JFK

Jacqueline Kennedy was determined to elevate her husband into a mythic figure and she set the stage for this by planting the “Camelot” myth in the mind of presidential chronicler Theodore White. Mrs. Kennedy recoiled at the idea that a nonentity like Lee Harvey Oswald had murdered her husband, noting that Jack “didn’t even have the satisfaction of being killed for civil rights . . . . It had to be some silly little communist. It … robs his death of any meaning.” Mrs. Kennedy’s myth has persisted into the 21st century through the works of Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., along with Ted Sorensen, Robert Dallek, Larry Sabato, Sean Wilentz, and countless others. For these chroniclers the Kennedy years were a brief, shining moment in which the world of ideas merged seamlessly, and gracefully, with the world of power. Schlesinger, the Kennedy family’s court biographer, wistfully observed that “the capital city, somnolent in the Eisenhower years, had suddenly come alive … [with] the release of energy which occurs when men with ideas have a chance to put them into practice.” Schlesinger’s view was shared by his colleague Ted Sorensen, the author of the worshipful biography Kennedy, published in 1965. Both men saw JFK, and later Robert Kennedy, as martyrs for world peace and racial equality.

The Kennedy legend celebrated by so many progressive politicians and scholars has distorted expectations of what the presidency can achieve, and in the long run eroded the prestige and effectiveness of the office. A century of progressive disregard for the Constitution, which began with Woodrow Wilson, and in which John F. Kennedy and his scholarly supporters played a key role, damaged our nation’s polity, possibly beyond repair. While Wilson, and Teddy Roosevelt to a lesser extent, laid the foundation for the modern presidency, it was John F. Kennedy’s movie-star persona, his charisma, conveyed through modern technology, that permanently embedded Kennedy’s personalized presidency in the American psyche. While many of Kennedy’s contemporaries took a more progressive stance on the issues, Hubert Humphrey, for instance on civil rights, or Adlai Stevenson on the Cold War, Kennedy captured the progressive imagination particularly after his murder in Dallas, when many progressives claimed that he was the victim of a conspiracy involving racist, right-wing extremists or the “deep state,” or a combination of both.

Despite the preponderance of evidence that President Kennedy expanded American involvement in Vietnam, was involved in a number of risky extra-marital affairs, including one with the girlfriend of the Chicago mob boss and another with a nineteen-year-old intern whom he shared with a White House staffer, and whose administration conducted multiple assassination attempts against Fidel Castro, he remains an admired figure among the American public and among presidential scholars. A Gallup Poll of Americans taken in 2008 ranked JFK at the top of the list in terms of presidents you wished “you could bring back” to be chief executive. JFK came in at 23% followed, by Ronald Reagan with 22%, Bill Clinton at 13%, and Abraham Lincoln at 10%. Another Gallup poll, this one taken in February, 2000, ranked Kennedy as “the greatest president ever.” The 2017 C-SPAN presidential leadership survey of historians and political scientists ranked President Kennedy eight overall, slightly behind Thomas Jefferson and ahead of luminaries such as Jackson, Wilson, and Eisenhower.

John F. Kennedy’s allure persists despite the fact that his presidency, the progressive presidency, promised too much of the federal government. The United States would do well to return to the constitutional presidency proposed by Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton, a proponent of an “energetic executive,” nevertheless acknowledged limits to what the presidency should do: it should concentrate on administering the government, conduct foreign negotiations, oversee military preparations, and if need be, direct a war. It should not attempt to bear any burden, nor should it engage in the kind of destructive hubris found in JFK’s proclamation that “man can be as big as he wants” and that “no problem of human destiny is beyond human beings.” The founding fathers understood something many progressives, including JFK’s “best and brightest,” did not: that the more you expand the roles and responsibilities of the presidency, and of the federal government writ large, the more you diminish it. It is important to note that the founders’ presidency provided both a floor and a ceiling that protected but also energized the office; without this, the office is trapped in an endless cycle of raised expectations followed by dashed hopes and rampant cynicism.