Cody Jorgensen is Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at Boise State University. His research interests include drug policy, gun violence, developmental and biosocial criminology, policing and forensics and quantitative methods.

The following is the second policy brief in a series that explores findings from the School of Public Service’s 7th Annual Idaho Public Policy Survey and places those results within their broader policy context.

The Police Mission

Fighting and controlling crime is the primary mission for law enforcement agencies. While crime control is not the only thing that police do, it is their public mandate and raison d’être (Bittner, 1990) and what the public expects from their police. The stereotypical image of police in our society is one of a crime fighter (or a soldier) fighting a war on crime, an image that police officers commonly embrace (McLean et al., 2020). Law enforcement affects crime rates via two primary means: deterrence and incapacitation.

When police deter crime they essentially prevent it from occurring in the first place. In this sense, police presence in a community sends a deterrence threat to members looking to take advantage of potential criminal opportunities. Fear of being caught by the police and subsequently punished induces the deterrent effect (Nagin et al., 2015), although obviously police cannot deter all crime.

Once a crime is committed, police are tasked with investigating it and ideally identifying and arresting the culprit(s). Taking a suspected criminal off the streets through arrest incapacitates them for a time and prevents them from committing more offenses while contained by the criminal justice system. By solving crimes, police can affect crime rates by incapacitating criminals (Cloninger & Sartorious, 1979).

This begs the question: Just how good are the police at solving crime and do the police meet public expectations of police performance in terms of solving crime?

Idahoans’ Expectations of Police Performance on Solving Crime

Boise State University’s School of Public Service/Idaho Policy Institute administered the 7th Annual Idaho Public Policy Survey in November 2021. The survey yielded a representative statewide sample of 1,000 Idahoans and collected data on a range of topics related to their interests.1 Two questions gauged Idahoans’ expectations of police performance on solving crime:

- On a scale of 0 to 100 percent, what percentage of violent crimes must police in Idaho solve in order for you to say that they are doing a “good job” at solving violent crime2?

- On a scale of 0 to 100 percent, what percentage of property crimes must police in Idaho solve in order for you to say that they are doing a “good job” at solving property crime3?

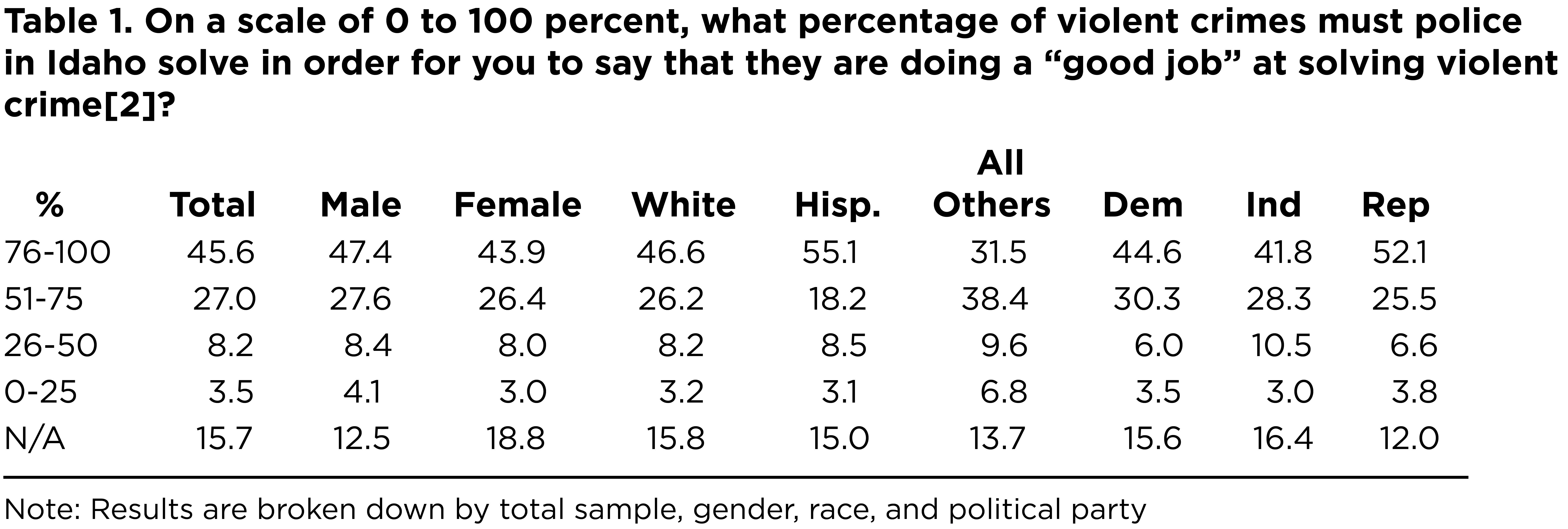

Tables 1 and 2 below show the results of these questions from the representative sample of Idahoans broken down by total sample, gender, race, and political party4. The results show that 45.6% of Idahoans expect the police to solve 76-100% of violent crimes in order for them to say that the police in Idaho are doing a good job at solving violent crime. For 27% of Idahoans, that percentage must be between 51-75%. For 8.2% of Idahoans, the police must solve 26-50% of violent crimes for them to say that the police are doing a good job, and for 3.5% of Idahoans, that percentage must be 0-25%. These expected percentages are generally similar across gender, race, and political party with a few exceptions. African-Americans and the “other” racial category in Idaho tend to have lower expectations of police than the general Idaho population.

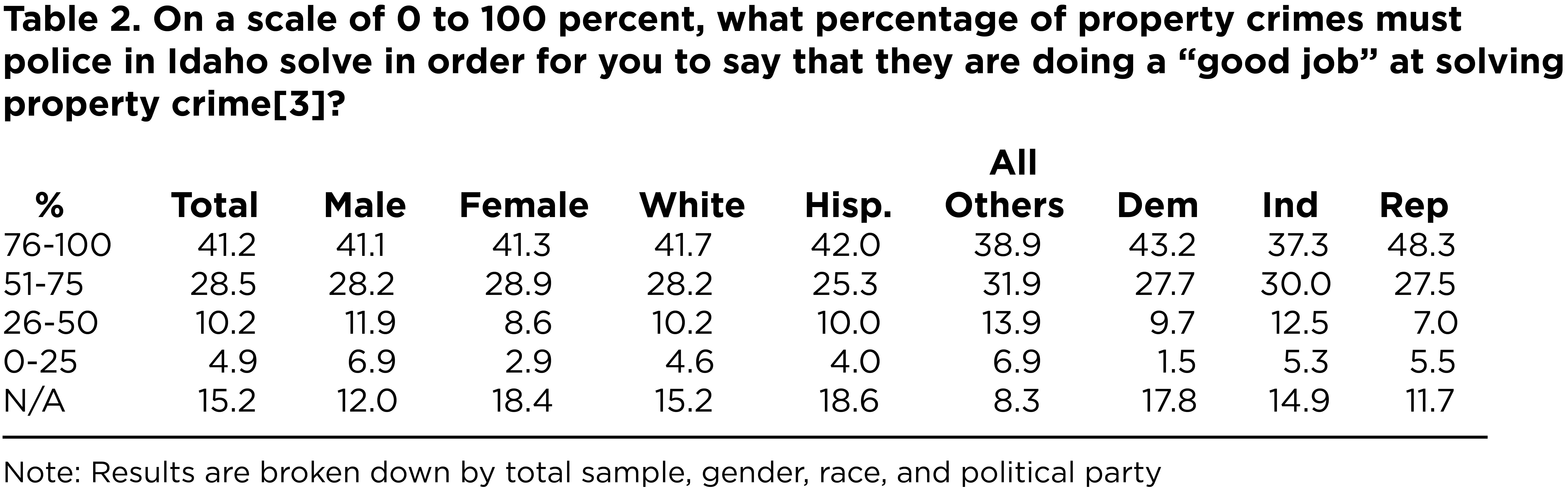

The results also show that Idahoans generally have similar expectations of police solving property crimes; however, the expectations are slightly lower for property crimes than for violent crimes. This suggests that Idahoans expect the police to be better at solving violent crime than property crime. The data indicate that 41.2% of Idahoans expect the police to solve between 76-100% of property crimes for them to say that the police in Idaho are doing a good job at solving property crimes. For 28.5% of Idahoans, that percentage must be between 51-75%. For 10.2% of Idahoans, the police must solve 26-50% of property crimes for them to say that the police are doing a good job, and for 4.9% of Idahoans, that percentage must be 0-25%. It should be noted that roughly 15% of the survey respondents did not answer these two questions.

Actual Police Performance on Solving Crime

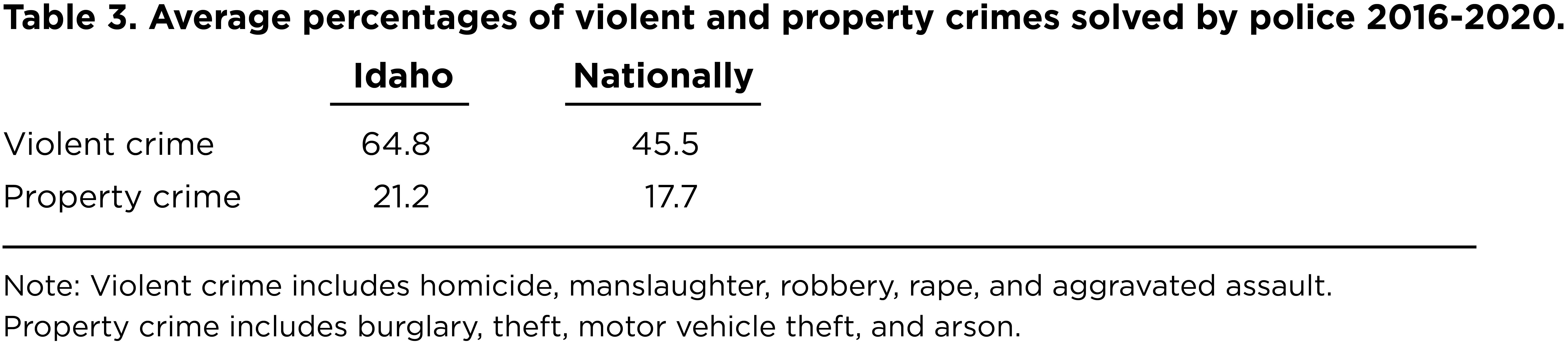

In order to put these survey findings in proper context, we need to examine the actual percentages of violent and property crimes solve5 by law enforcement in Idaho. Table 3 below shows the percentages of violent and property crimes solved by Idaho police and police nationally averaged from 2016-2020. The data on crimes solved by police in Idaho come from the Idaho State Police (ISP) Uniform Crime Reporting program, while the data on crimes solved by police nationally come from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Uniform Crime Reporting program.

The data show that over the past five years, police in Idaho were able to solve 64.8% of violent crimes through arrest, and 21.2% of property crimes on average. Law enforcement in Idaho did a better job at solving crime than law enforcement nationally. That said, 38.7% of Idahoans expect the police in Idaho to solve up to 75% of violent crimes in order for them to say that police in Idaho are doing a good job at solving violent crime. This means that law enforcement agents in Idaho are not meeting the expectations of 45.6% of Idahoans who expect police do solve more than 75% of violent crimes.6

For property crime, 4.9% of Idahoans expect the police in Idaho to solve at least 25% of property crimes in order for them to say that police in Idaho are doing a good job at solving property crime. This leaves 79.9% of Idahoans believing that law enforcement agents in Idaho are not doing a good job at solving property crime.7 In sum, the data show that the police in Idaho are not meeting the “good job” expectations Idahoans have of them in terms of their ability to solve both violent crime and property crime, although Idaho police come closer to that metric at solving violent crime.

It is useful to also break down the percentages of Idaho crimes solved by crime type. On average over the past five years, authorities in Idaho have been able to solve 66.5% of homicides, 41% of rapes, 45.1% of robberies, 70.9% of aggravated assaults, 17.7% of burglaries, 24.5% of thefts, 20.9% of motor vehicle thefts, and 31% of arsons.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

The data presented above show that there is a disconnect between Idahoans’ expectations of police performance and actual police performance in terms of solving crime. This disconnect may or may not matter in the grand scheme of things for interested stakeholders, particularly the police, as Idahoans’ expectations are likely unrealistic and many crimes are simply unsolvable. The police can do everything reasonably possible, and do so correctly, and still have the investigation come up empty handed. In recent memory, the police have never been able to solve as many crimes as the people of Idaho expect.8 What is more, the percentage of crimes solved by police remains relatively stable across time. As such, it may not be in the best interests of stakeholders to placate the public’s unrealistic expectations.

On the other hand, it may be worthwhile to address this disconnect and bridge the gap between Idahoan’s expectations of police performance and actual police performance. One way to accomplish this goal would be to reduce the public’s unrealistic expectations to something more in line with reality. The public’s unrealistic expectations are likely due to a lack of information. People simply do not know enough about policing to form realistic opinions of police performance; and what they think they do know often comes from TV shows which can warp their beliefs (Callanan & Rosenberger, 2011). In this case, the police could improve communication with community members and be transparent about the realities of police investigations. However, this would probably require law enforcement to acknowledge the limitations surrounding police work.

Another way to accomplish the goal of bridging the performance gap would be to increase the percentage of crimes that police solve. Police in Idaho already do a better job at solving crime than police nationally. However, there is always room for improvement. Law enforcement agencies can take steps to foster a healthy relationship between them and the community they serve (Hunter et al., 2000). Community members are more likely to cooperate with the police and help them with their investigations when the police are viewed as legitimate and trustworthy by the public (Tyler, 2021).

Civilians are a vital source of information to police investigations. After all, they are the ones who report crimes to the police and tell them who the suspect is, where they live, who they hang out with, where they work, etc. If the police-community relationship is fractured, community members are less likely to volunteer this kind of information to the police. It is in everyone’s best interest, including agents of law enforcement, to maximize the health of the police-community relationship. One possible advantageous side effect of doing so could be that the police solve more crimes. That is a win-win scenario.

References

Bittner, E. (1990). Aspects of police work (p. 30). Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Callanan, V. J., & Rosenberger, J. S. (2011). Media and public perceptions of the police: Examining the impact of race and personal experience. Policing & Society, 21(2), 167-189.

Cloninger, D. O., & Sartorius, L. C. (1979). Crime rates, clearance rates and enforcement effort: The case of Houston, Texas. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 38(4), 389-402.

Hunter, R. D., Mayhall, P. D., & Barker, T. (2000). Police-community relations and the administration of justice. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

McLean, K., Wolfe, S. E., Rojek, J., Alpert, G. P., & Smith, M. R. (2020). Police officers as warriors or guardians: Empirical reality or intriguing rhetoric?. Justice Quarterly, 37(6), 1096-1118.

Nagin, D. S., Solow, R. M., & Lum, C. (2015). Deterrence, criminal opportunities, and police. Criminology, 53(1), 74-100.

Tyler, T. R. (2021). Why people obey the law. Princeton university press.

Notes

- The survey methodology employed allows the results to be generalizable to all Idaho residents.

- Violent crime refers to homicide, rape, robbery, and assault, etc.

- Property crime refers to theft, motor vehicle theft, burglary, and arson, etc.

- Results can also be broken down by age, income, education, residency, and many other factors. These results are available upon request.

- Decades of clearance rate data from ISP and FBI are publicly available.