Matthew May serves as a postdoctoral associate with the Idaho Policy Institute and holds a Ph.D. in Public Policy and Administration from Boise State University. His research interests include elections, electoral policy, and the legislative process, paying particular attention to the implications surrounding a state changing from one primary system to another.

Fewer state employees are turning out to vote in Idaho’s primary elections. While turnout can be affected by a number of factors, a survey of Idaho state employees suggests that this behavior may be driven, at least partially, by the state’s recent shift to a closed primary system. Under the previous “open” system, no record of a voter’s partisan affiliation was kept, leaving them free to participate in the partisan primary of their choice. Under the new “closed” system, voters must publicly declare a partisan affiliation beforehand in order to participate.

A state’s choice of primary system can influence election outcomes – it can affect voter participation and the partisanship of the winning candidate. There are additional costs attached to primary systems, though, ones that have been largely hidden from view up until now. Data indicates that under the closed primary, state employees are affiliating with political parties at a lower rate than the average Idaho voter. In order for policymakers (and the public) to assess the costs of a primary system fairly, it is important to first define what those costs are.

THE PRICE OF CLOSED PRIMARIES?

When a state shifts from one primary system to another, the most direct change occurs in the voting process itself. At a superficial level, the effect of such a shift might seem minimal; depending on the direction of the change (from open to closed or vice versa), it simply adds or removes a step to the voting process. Other effects also exist, however, and are often more difficult to observe. Until recently, most scholarship on these effects focused on voter turnout (arguing that more closed systems depress voter turnout) and partisanship (arguing that more closed systems produce more partisan candidates). I argue that another importance that has been largely overlooked concerns administrative discretion and the potential conflict that arises when professionally neutral state employees must publicly declare a partisan affiliation.

How would this affect state employees? Simple. Policymakers implement public policy via the professional bureaucracy (a term I use not as a pejorative, but simply to refer to all state employees). A key dimension of policymaking is how much authority to delegate to that bureaucracy—how much discretion or latitude should they be afforded in how they actually implement public policy? When you introduce the partisan affiliation of state employees into the mix, it can potentially influence a policymaker’s decision to delegate authority, as policymakers may be more inclined to “trust” politically like-minded state employees. Moreover, fear of this intervention may, in turn, influence the actions of the state employee, as it incentivizes them to remain unaffiliated in order to maximize their professional discretion. More succinctly, it presents state employees with the following dilemma: (1) register with a political party publicly or (2) opt to not participate in primary elections. Under the first option, a state employee risks less discretion from policymakers. Alternatively, under the second option, they lose the ability to influence the outcome of a primary election. (This dilemma also applies to other professions, such as journalists and academics, although the scope of my research was limited to state employees.)

THE CASE OF IDAHO

In 2011, the state of Idaho shifted from an open primary system to a closed primary system. The change was the result of a 2007 rule adopted by the Idaho Republican Party Central Committee to allow only registered party members to participate in its nomination of candidates. When the state legislature failed to change its primary system in the subsequent legislative session, the Republican Party sued the state and won. Consequently, in 2011 the Idaho legislature passed House Bill 351, which established a statewide party registration system for voters and defaulted primary elections in Idaho to party-members-only (although parties retain the right to open their own primaries if they choose).

In a single-party-dominant state like Idaho, opting out of the primary could effectively cut state employees out of the political system entirely. Over the past 22 years, nine of 12 election cycles have seen over 40% of the seats in the Idaho Legislature have no major-party challenger in the general election. In essence, winning the primary wins the legislative seat. When the primary electorate effectively determines the outcome of a legislative contest, being able to participate in that election carries great importance. As such, the dilemma state employees face over whether to declare their party affiliation or avoid questions about their professional independence is very real, as the tradeoff may be losing the ability to influence their own representation.

There is anecdotal evidence that some state employees in Idaho have indeed opted to exclude themselves from primary elections. In 2012, both the Legislative Services Office (which consisted of 66 full-time employees at the time) and the Office of Performance Evaluations (which consisted of eight full-time employees at the time), chose not to participate in primary elections in order to preserve their status as nonpartisan staff. In so doing, they sought to preserve their roles as non-partisan professionals that could be relied upon by both the majority and minority parties in the Idaho Legislature. With opting out of the primary occurring in at least two state offices (admittedly two offices that closely interact with the legislature), it bears asking whether these offices are outliers due to their proximity to the Idaho Legislature itself or if the act of opting out by government employees is more widespread throughout the state.

ANALYZING THE EFFECTS OF IDAHO’S PRIMARY SHIFT

Most of my analysis is based on comparing voting behavior prior to the primary system shift with voting behavior after the shift. I use four indicators of the effect of the shift on state employees: (1) A state employee’s willingness to participate in primary elections; (2) Actual voter turnout levels of state employees in primary elections; (3) Partisan affiliation rates among state employees; and (4) State employees’ self-described levels of concern over being perceived as partisan in their professional capacity.

To assess how widespread this phenomenon was, I took a two-pronged approach using both survey data and voting history data. I anonymously surveyed staff in four Idaho state agencies/entities: the Idaho State Department of Agriculture, the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality, the Idaho Supreme Court, and the Idaho Transportation Department. The breadth of public policy covered by these agencies, as well as the relatively large number of employees working in them, make this sample generally representative of the larger pool of state agencies and maximizes the opportunity to gain insight into the motivations of a typical state employee. This was supplemented by a separate original data set that looked at the voting history of a random sample of over 1,400 state employees in Idaho and tracked their electoral participation over time. (For more information on how I conducted this study, see here.)

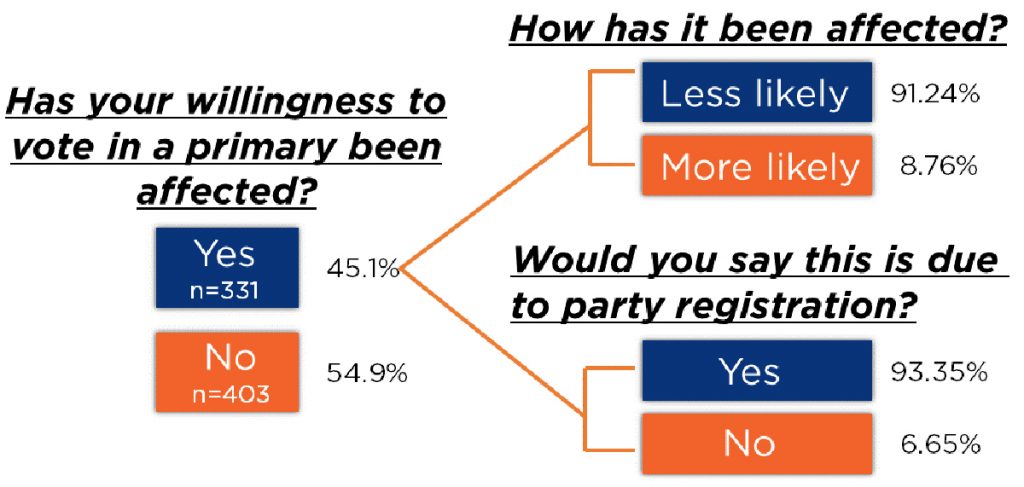

The first indicator is one of the more direct measures of the primary system’s effect on state employees in Idaho. When asked whether their willingness to vote in a primary election has changed since the implementation of the closed primary:

- Approximately 45% of survey respondents said yes, their willingness to vote in a primary had been affected.

- Roughly 91% of those who answered “yes” said that they were now less likely to vote in a primary, while only 9% said they were more likely to vote.

- 93% of those who answered “yes” attributed their change in behavior to the party affiliation requirement of the closed primary system—only 7% said that their change in behavior was unrelated.

With nearly half of all survey respondents saying the closed primary is a direct cause of a change in their voting behavior, there is strong support for the argument that the primary system shift is producing a noticeable effect among state employees.

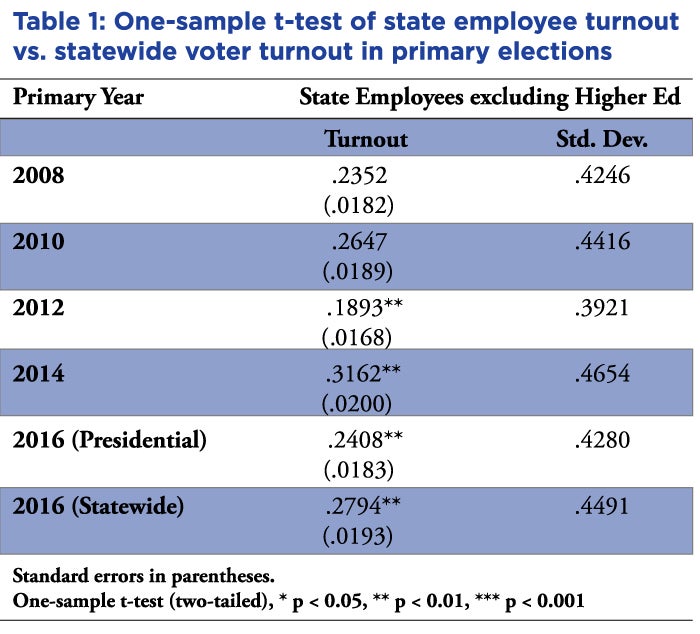

When it came to voter turnout, I found evidence of a decline in participation among state employees under the new primary system. Approximately 64% of survey respondents reported that they had voted under the open primary, but only 58% had done so under the closed primary. Voting history data corroborates this finding, with average voter turnout for all Idaho voters declining 4% under the closed primary. State employee turnout saw a decline in the first closed primary, as well, especially among those who remained unaffiliated. There are also indications that the primary system shift has produced a more substantial effect among state employees who work for state agencies versus state employees who work for a higher education institution. More specifically, voting history data shows a statistically significant difference in the turnout rates of (non-higher ed) state employees compared to all voters in Idaho. Moreover, this difference was present only in the period of the closed primary. This suggests that the introduction of the new primary system could be responsible for that difference. These results are summarized in Table 1.

The evidence suggests that the closed primary has, at least partially, depressed state employee turnout in Idaho’s primary elections.

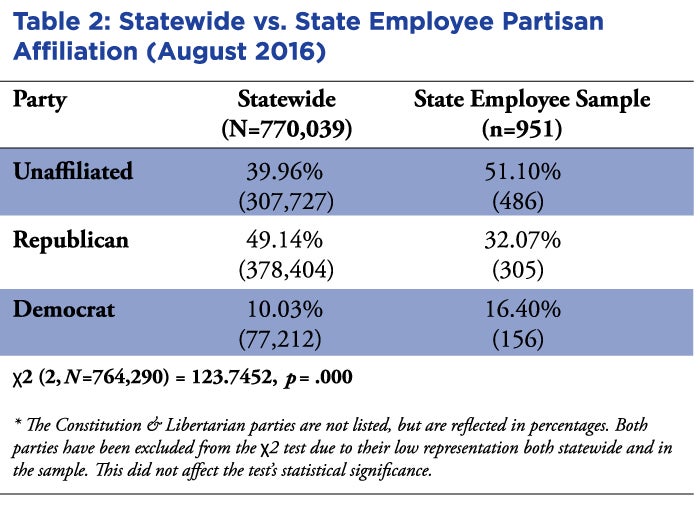

Partisan affiliation rates told a similar story. Survey respondents were almost evenly split between those who had affiliated with a political party (46%) and those who had not (44%), with the remainder (9%) indicating they were unsure of their status. For comparison, approximately 60% of all Idaho voters had declared a partisan affiliation as-of August 2016. This suggests that state employees are affiliating at a lower rate than the average Idaho voter. Affiliation rates from the voter history data, as shown in Table 2, are consistent with these findings. Approximately 51% of state employees in the sample remain unaffiliated. The difference in affiliation behavior between state employees and the general public is statistically significant, suggesting that state employees have reacted to the primary shift in a way that is meaningfully distinct from the average Idaho voter.

For the final indicator, I found that concerns about being perceived as partisan have also risen among state employees. While only 17% said they were concerned over being viewed as partisan professionally under the open primary system, that number has increased to 26% under the closed primary. This increase suggests that there is a growing unease among state employees regarding the closed primary and how it could affect them professionally. This concern, in turn, may be one of the drivers behind their decision to participate or not.

CONCLUSION

Although the evidence reported here seems to indicate Idaho’s switch to the closed primary had significant effects on the political choices available to the state’s bureaucracy, we should also keep in mind that there have only been four primary elections since Idaho’s shift to a closed primary (2012, 2014, the 2016 presidential primary, and the 2016 statewide primary). This means voters are still adjusting to the new system and what it means, and therefore more attention must be paid to it over time.

That said, taken together these four areas show that there are clear indications that state employees are concerned over the shift and it has so far affected their voting behavior. Why should the average Idahoan care? Some could argue that reducing the influence of state employees is a positive outcome. They might also argue that state employees’ behavior should be adjusted to be more neutral and that they should stay out of the partisan arena entirely. Others might point out that, since opting out of primary elections is voluntary, the issue lies with the state employees rather than the policy. These are valid critiques. They are largely, however, discussions of what ought to be the response to an issue that has, thus far, gone unnoticed.

When it comes to primaries, we are used to a person’s party affiliation affecting whether they can vote or not. Whether a person works for the government seldom factors into the conversation. My research indicates that it should, as it is producing a noticeable effect that is meaningfully different compared to the average Idaho voter. The question of what (if anything) ought to be done about it falls outside the scope of my work. To assess public policy, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of that policy’s effects. When it comes to Idaho’s primary system, the full ramifications of the choice state employees face have only begun to manifest and warrant further study. There is still much about primary systems that we do not know and understanding the full impact of a given primary system is critical as more and more states consider shifts. Idaho provides an opportunity to gain further insight. Only then can we truly inform the debate of which primary system is right for us.