Jillian Moroney is a postdoctoral fellow at Boise State University. She enjoys working at the interface between society and natural resources. Her areas of research and expertise include social assessment and stakeholder engagement regarding natural resource related topics including bioenergy, forestry, irrigation, and farmland. She earned her Ph.D. in environmental science and her M.A. in bioregional planning and community design, both from University of Idaho, and her B.A. in geology from Western Washington University.

The northwest United States has an abundance of forest residuals – underbrush and slash– left over from harvesting and forest restoration treatments, as well as mill and urban wood waste. All of these feedstocks are forms of woody biomass. This abundance of woody biomass creates considerable potential for wood-based bioenergy development in the region, particularly for advanced liquid biofuels, such as biojet fuel. Since the region is already known as a global center of aviation innovation, thanks to companies like Boeing, the northwest has a significant interest in developing renewable aviation fuels.

One way to accomplish this is by utilizing bioenergy feedstock such as slash—the tops and limbs from trees that are left over from timber processing, generally referred to as “post-harvest residuals.” These feedstocks can produce heat, electricity, and liquid biofuels. However, we currently don’t know the realistic economic, environmental, and social ramifications of utilizing these resources. For instance, the carbon neutrality of wood-based bioenergy is strongly debated, especially when we take into account the fossil fuel used to harvest, transport, and process the biomass, or the impacts from different replacement species and their growth rates. On the flip side, many forest residuals are either burned or left to decay in the forest, leading to more CO2 entering the atmosphere. We surveyed stakeholders in Idaho, Montana, Washington, and Oregon to determine what benefits and drawbacks they perceived from harvesting and processing biomass in their communities.

While many alternative fuel options are being developed for ground transportation and electricity generation, the aviation sector will rely on high energy-density liquid fuels with the same characteristics as petroleum-based jetfuel for the next twenty to thirty years simply because of the way planes are currently designed. The Northwest Advanced Renewables Alliance (NARA) – a collaboration among universities, government, and industry— examined how to produce liquid biojet fuels from slash and other forest waste and urban wood waste in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana. NARA examined the economic and environmental feasibility, as well as the social sustainability of a regional wood-based biofuels supply chain that involves feedstock harvesting, transportation, and processing. For a sustainable wood-based biojet fuel industry to thrive, not only is it important to understand the economic and environmental aspects, but also its social acceptability. Ultimately stakeholders, or those who directly influence and are affected by a policy or industry decision, will be the ones impacted by its production, employed in the industry, and who will use the fuel and define forest health and management practices for their region. Previous studies found stakeholder support for, and perceptions about, the emerging biofuels industry are important for determining whether they will accept or reject facilities opening in their communities.

STAKEHOLDER PERCEPTIONS

How do we even begin to understand if stakeholders support an emerging industry, or why they might support or oppose it? Go to the source: the stakeholders. In order to understand stakeholder perceptions better, a survey was conducted in the four state region of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. While the scope of the survey was broad, one main focus of the survey was to determine potential benefits and drawbacks of using woody biomass from post-harvest forest residuals for biofuels production as perceived by stakeholders. In addressing these topics, we can identify areas of consensus and differences between regions, and begin to understand more about what potential benefits stakeholders hope to see, or drawbacks they are concerned about, in the face of this emerging industry.

To understand people’s perceptions of this specific industry, in 2013 we talked with and surveyed over 350 people who managed the feedstock, worked in forests, dealt in forest products, or owned land. We sent surveys via post and email to private foresters, primary and secondary wood products producers, harvesters and haulers, and other stakeholders directly involved in the forest industry; members of environmental organizations, local resource managers, recreation and wilderness outfitters, and forest or natural resource managers from tribes; those who operate at a city or county levels including university educators, economic and business development professionals, elected officials, and local business investors; public foresters, academic researchers, state or federally employed biologists, and federal district rangers.

While the survey generated a wealth of quantitative information indicating how much people know about producing liquid biofuels and what specific collecting and refining processes they would tolerate in their communities, some of the most interesting information was more qualitative in nature and was collected through open ended questions. Findings from these types of questions are highlighted below.

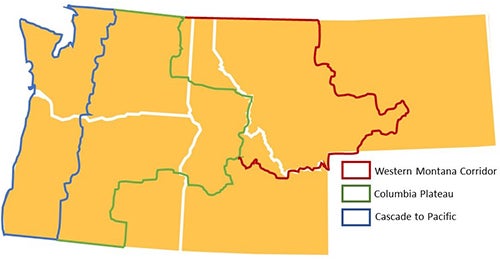

The survey asked “What are the positive effects, if any, of removing woody biomass?” and “What are the negative effects, if any, of removing woody biomass?” Additionally, it asked participants if they had any questions about using woody biomass for biofuels in their region. Depending on how the research area is divided, interesting trends emerged both regionally and by individual state. The larger northwest region was divided into three smaller regions: Cascade to Pacific (including western Washington and Oregon), Western Montana Corridor (including western Montana, northern Idaho, and northeastern Washington), and Columbia Plateau (including eastern Washington and Oregon and southern Idaho) by geographical and social similarities (Figure 1).

POSITIVE EFFECTS OF REMOVING WOODY BIOMASS

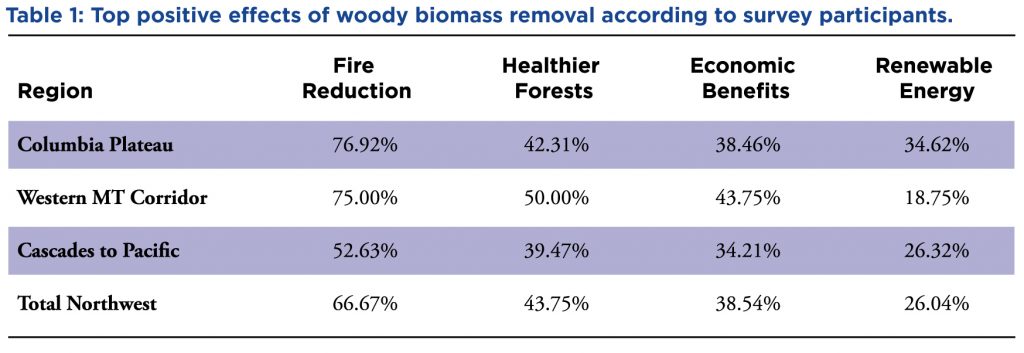

The majority of survey participants could think of multiple positive effects resulting from removing woody biomass. The top four, regardless of region, were fire reduction as a result of removing excess fuel, overall healthier forests, economic benefits, and the benefit of renewable energy (Table 1).

We saw participants from the Columbia Plateau and the Western Montana Corridor mention fire reduction almost 25% more frequently than participants from the Cascade to Pacific region, most likely because of the dryer climates and large scale destructive wildfires seen in Idaho, Montana, and eastern Oregon and Washington. When responding to the question “What are the positive effects, if any, of removing woody biomass?” one participant from the Western Montana Corridor responded that it “allows revenue stream for loggers, haulers and landowners. Allows landowners opportunity to treat acreages that might otherwise not get treated. Removes fuels from the forest, improving fire conditions. Gives remaining trees, forbs and grasses more light and water.” Another participant from the Columbia Plateau noted that it “improves forest health, reduces exess [sic] fuels, creates jobs, provides fiber to mills and creates opportunities for woody biomass utilization for renewable energy.”

NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF REMOVING WOODY BIOMASS

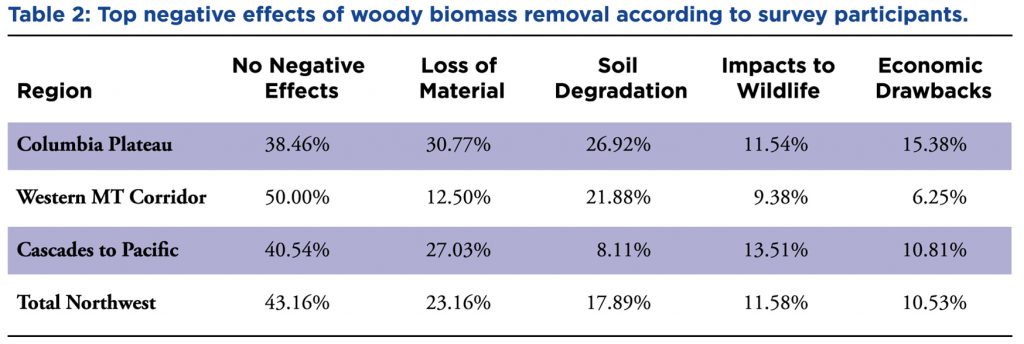

While a percentage of stakeholders did have concerns about the negative effects of removing woody biomass, the majority said they saw no negative effects, especially if removal was done correctly. One survey participant from the Western Montana Corridor said “If done properly there are none.” Many participants simply wrote “none” when referring to the negative effects they expected to see as a result of removal. Other concerns that were mentioned most frequently were loss of material needed to continue the natural nutrient cycle, soil degradation as a result of harvesting practices, impacts to wildlife habitat, and economic drawbacks (Table 2).

Participants from the Western Montana corridor and the Columbia Plateau had similar concerns about the effects removal would have on soil. A participant from the Western Montana Corridor said they saw “some soil depletion, habitat alteration” as negative results, and a participant from the Columbia Plateau saw similar drawbacks, listing “less biomass to improve the soil and provide habitat.”

While less concerned about the effects on the soil, participants from the Cascades to Pacific region were concerned about loss of materials for nutrient cycling, impacts to wildlife, and economic drawbacks. “Without a comprehensive industry infrastructure in place (loggers, truckers, multiple conversion facilities [both by type and location]) the negative effect of removing woody biomass is that it is very costly,” said one participant from the Cascade to Pacific region. Those from the Western Montana Corridor were less concerned about economic drawbacks, potentially because of the harvesting, trucking, and processing facilities and workforce that already exist in the area as a result of the lumber industry.

STAKEHOLDER QUESTIONS

Survey participants were also asked if they had any questions about an aviation biofuel supply chain starting in the northwestern United States. Regardless of state or region, the top two questions from stakeholders were the same: “Is it economically feasible?” and “What are the environmental impacts going to be?” Beyond these two questions, an interesting pattern emerged when the questions were examined by state, and the issues that arose in each state reflect the constraints or opportunities that would face the industry if locating in these communities.

Participants from Idaho asked the most questions about accessing feedstock on public lands, most likely because over 60% of the land is either state or federally owned. Participants from Washington asked the most questions about using municipal waste from construction and demolition as a potential feedstock; this is likely because of the rapid growth and development in larger Washington cities, which produces this kind of debris. Oregon residents were more concerned about the environmental implications than any other state. Finally, the most frequently asked question from participants from Montana was, “When can we start?” Information gathered from conversations with Montana participants, as well as their survey information, indicated that regions of Montana traditionally dependent on lumber and forest-product industries see these biofuels as an opportunity to revitalize some of their communities and bring employment opportunities to the region. One participant from Montana pointed out that “while other areas may see logging trucks as a drawback, we see a logging truck and know that means there are jobs in our community.”

SO, WHEN CAN WE START?

A successful wood-based biofuels supply chain in the northwest would depend on a broad network of professionals, communities, and infrastructure. There must be a consistent source of feedstock as well as a cost-effective way to bring it out of the woods. Even when these conditions exist, community support can play a role in the ultimate success or failure of facilities opening at the community level. Other studies done in the Pacific Northwest indicate that many projects falter because of lack of community support, and resistance and litigation that can result. A recent study by Newman et al (in review) interviewed stakeholders across the northwest regarding forest-based bioenergy development opportunities, concerns, and obstacles. Findings show that most participants were at least cautiously supportive of bioenergy development, given projects promote forest health and benefit forest-dependent communities. Stakeholders’ primary concerns related to negative environmental and community impacts.

Similar to other studies, we saw cautious optimism in the stakeholders we surveyed and spoke with. Many see that there are benefits to removing woody biomass to support a liquid biofuels industry that would positively impact forest conditions, regional economies, and reduce fire hazards. However, respondents do have concerns related to the negative impacts on soil and wildlife by the removal of forest residuals. Many of the questions stakeholders asked were place specific, indicating that participants are thinking about what biofuels operations would look like in their communities, and what impacts or benefits might directly affect them.

In response to many participants who asked “When can we start?” The answer is, we’ve already started. On November 14, 2016, the first commercial flight using the world’s first renewable, alternative jet fuel made from forest residuals flew from Seattle, Washington, to Washington D.C. The fuel was produced by the Northwest Advanced Renewables Alliance (NARA) from feedstock sourced from tribal lands and private forests in the northwest. Organizations like NARA are researching the benefits and potential negative effects related to a wood-based biofuels industry. To find out more, visit the NARA’s website.

The Northwest Advanced Renewables Alliance (NARA), supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 2011- 68005-304 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.