Dr. Lisa Meierotto is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. She teaches in the Global Studies and Environmental Studies programs. Meierotto earned her Ph.D. in environmental anthropology from the University of Washington, and also holds an M.A. in International Development and Social Change from Clark University. Previous research focused on the environmental impacts of undocumented immigration on the U. S. Mexican border. Current research focuses on human rights and environmental justice, especially considering the social and environmental ramifications of global migration trends.

Dr. Rebecca Som Castellano is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Boise State University. She earned her Ph.D. in Rural Sociology at The Ohio State University, her M.A. in Sociology from the University of Kentucky and her B.A. in interdisciplinary studies from Fairhaven College at Western Washington University. She has worked in a range of food system jobs, including farmers’ market management and farming. Her areas of expertise include rural sociology; the sociology of food and agriculture; gender and development; and stratification. Her current research examines farmer adaptation to climate change, as well as stratification in the changing agriculture and food system. She has been awarded regional and national awards, including a USDA National Needs Fellowship, a Rural Sociological Society Thesis Award, a Coca Cola Critical Difference for Women Award, and the American Sociological Association Community Action Research Grant.

Much of what Americans consume in the U.S. is produced by farm workers of Latina/o descent. The berries, nuts, meat, and pasta that we eat, and the hops and grapes that we drink, for instance, are made possible in large part by the skilled labor of farm workers. Farm workers, however, tend to be socially, geographically, and economically disadvantaged. They often labor in rural areas, and are therefore physically invisible to the majority of Americans. Farm workers tend to be racial and ethnic minorities, and are often immigrants. They are often poorly compensated for their labor. The multiple forms of oppression that they experience further contribute to their isolation and invisibility. Similar to the rest of the U.S., farm workers in Idaho face social and economic challenges. While Idaho farm workers face long hours, low wages, and inadequate housing, they continue to produce for the consumption habits of Americans, as well as for global markets. Building on our previous work in immigration studies (Meierotto) and agriculture and food system inequality (Som Castellano), we decided to conduct research examining the well-being of farm workers and their families in Idaho.

We began conducting ethnographic research with Idaho agricultural workers In December 2016. We wanted to learn more about the challenges farm workers face in maintaining their well-being, paying particular attention to household food security and the labor of food provisioning. What we learned was illuminating.

HOPS AGRICULTURE IS BOOMING IN SOUTHWESTERN IDAHO

The southwestern part of the state has seen an increasing agricultural focus on the production of hops in recent years. Driving the shift is consumer demand for craft micro-brew beer. According to the National Brewers Association, craft beer sales in the United States (U.S.) were up by 12.8 percent in 2015 (Brewers Association 2016). Interestingly, the production of hops is highly concentrated, and over 99 percent of total hops production takes place in just four counties spread across Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, including Canyon County (Lowe et al. 2016). While craft brewing has become an important part of the cultural landscape in the Northwest, it is also an important component of the regional economy. Idaho hops production in 2015 was valued at $30.8 million. Importantly, the production of hops is a highly labor intensive crop that requires precision. Thus labor needs are high.Interestingly, the production of hops is highly concentrated, and over 99 percent of total hops production takes place in just four counties spread across Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, including Canyon County.

FARM WORKER MIGRATION IS DECLINING

According to the US Department of Labor National Agricultural Worker Survey 2013-2014, sixty-eight percent of hired farmworkers nationally were born in Mexico, while 27 percent were born in the U.S.. The number of US citizens working in agriculture has been steadily increasing throughout the past two decades. Since 2001 the rates of citizens working in agriculture has increased from 21-33 percent. In other words, fewer farm workers are migrating in the traditional sense (e.g. travel back and forth to Mexico on a seasonal basis).

These numbers make sense. Border crossing became much more difficult and dangerous in the early 1990s as a result of “Prevention through Deterrence” border security policy. As a result, we have a situation today where farm workers have “settled” in rural communities (defined by the USDA as working at single location within 75 miles of their home).

Indeed, rural Idaho would be in population decline were it not for Hispanic communities: from 2010 to 2014: rural Idaho’s Hispanic population grew by 9%, while its non-Hispanic population decreased by 1%. Twelve percent of Idaho residents today identify as Latina/o. In Canyon County, however, where the majority of hops production is located in the state, the population is 25% Hispanic, (primarily of Mexican origin) the highest of any county in the state. And in the area with the greatest concentration of hops production, the Hispanic population is actually closer to 75%. For example, in the town of Wilder, which is surrounded by hops fields, the vast majority of Latina/o families moved into the area prior to the 1990s. Today, Wilder is the first city in Idaho to elect an all Latino City Council. Indeed, rural Idaho would be in population decline were it not for Hispanic communities: from 2010 to 2014: rural Idaho’s Hispanic population grew by 9%, while its non-Hispanic population decreased by 1%. Statewide, most of Idaho’s Hispanics (70%) were born in the U.S., and the vast majority (79%) are U.S. citizens.

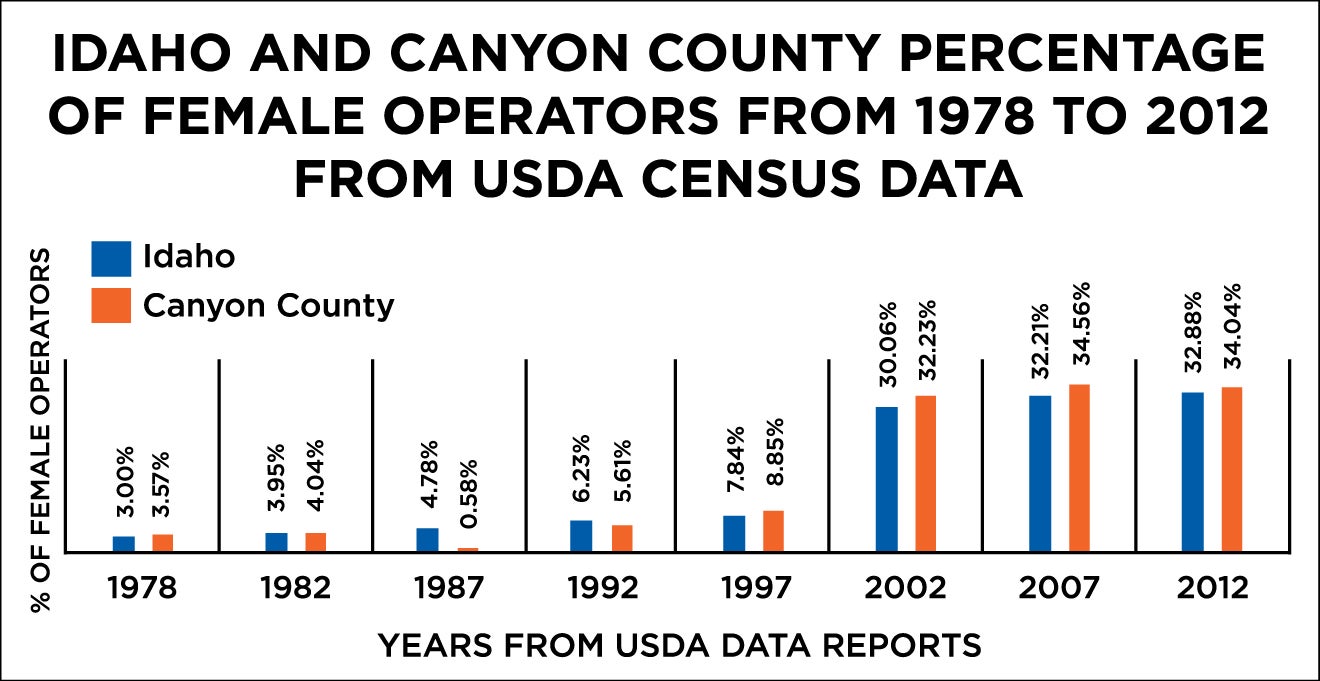

PRESENCE OF WOMEN IS INCREASING

Meanwhile, there also appears to be a gender transition occurring among Idaho’s agricultural workers. Women represent an increasingly large percentage of the agrifood labor force in the U.S. and beyond, which is sometimes referred to as the feminization of agriculture. At the national level, men make up 72% of the crop labor force. But the high proportion of men in agriculture does not match our initial observations of labor in the hops industry. During data collection we observed that women make up approximately half of the hops workforce. We have observed and talked with women at multiple levels of hops agriculture, ranging from planting, repairing wires, driving tractors and processing ripened vines of hops cones. When asked about the presence of women in the hops fields, it has been expressed that women possess many of the qualities that make for good agricultural workers, including strong work ethic, reliability, and the ability to perform high-level precision-labor.

The feminization of agricultural labor in Idaho raises a number of interesting questions regarding farm worker well-being. For example, are there different ways that women farm workers need social support—things like child care, grocery store access and flexible working hours? Do women agricultural workers face additional challenges in providing food for their families? Below we discuss initial findings related to food provisioning.

CHALLENGES IN FOOD PROVISIONING AMONG FARM WORKERS

Multiple reports have found that the rate of food insecurity among U.S. farm workers ranges between 20 and 93 percent. In our pilot research, we found that a majority of our respondents had experienced some degree of food insecurity (71%). Even more reported that the high cost of food influenced their ability to get the food they would like to have, and that they lacked sufficient money to get the food they would like to have (79%).

Risk of food insecurity, as well as a range of other factors, may complicate the labor of food provisioning for farm workers and their family members. Food provisioning refers to the labor involved in planning meals, procuring food, preparing meals, and cleaning up after meals. Below, we describe some of the factors that may influence food provisioning among farm workers, building on previous literature as well as initial data we have collected. We also discuss strategies that farm workers are using to deal with the constraints they face in their food provisioning.

- Gender: The feminization of agriculture makes gender an important consideration when examining food provisioning among farm workers, particularly given that women remain responsible for food provisioning, even when working outside of the home for pay. Farm work can be a particularly intense form of employment, as it is noted for long hours and exhausting schedules. It is therefore important to consider how gender interacts with this specific form of employment when examining the labor of food provisioning.

- Immigration status: While we see a transition towards more US citizens working in agriculture, the fact remains that some 45,000 undocumented immigrants work in Idaho. Immigration status influences access to safety nets, particularly the SNAP program, and influences the social experiences of farm workers in rural communities. Measures that could ease some of the mental, emotional and physical burdens of food provisioning for Latinx farm workers may be inaccessible for them, particularly those who are not documented. Based on data from the National Agricultural Workers Survey7% of undocumented farm workers used WIC between 1993-2009 and 12.4% of documented households utilized the WIC program. While children in a household may be qualified for SNAP based on their citizenship status, if their parents are not qualified this may act as a deterrent for them receiving these benefits.

- Geography: The majority of farm workers we have interviewed live at least 20 miles from a large supermarket. Not surprising, our respondents reported that driving to these large supermarkets is necessary for feeding their families on their limited budgets. While most people reported having their own vehicles, some respondents noted that elderly or “illegal” workers have challenges accessing the large chain stores. The long distances that must be traveled to gather food consumes a great deal of time for an already time-stretched population. During planting and harvest season many people work 12 hour days, seven days a week. This does not leave much time for the long drive to purchase groceries.

- Housing Quality: Many of the women and families we interviewed and surveyed live in low-income housing. Some farm workers live in USDA subsidized “Labor Camps.” These are housing projects developed in the 1940s by the USDA as a way to increase seasonal farm labor in rural locations. These camps were traditionally filled with temporary workers from Mexico. Today, however, the camps serve as low-income housing in rural Idaho. Camps are still subsidized by the USDA, though some have opened to non-agricultural low-income families. See, for example, the Caldwell Housing Authority. Poor quality housing may influence food provisioning in a number of ways, including limiting the ability of people to store and cook food.

- Children: Having children can influence the labor of food provisioning. In our interviews and observations we have heard a number of times that children can make the labor of food provisioning more challenging, as it is more people to feed and more preferences to address. At the same time, we observed women also finding joy in providing food for their children, and their families more broadly. This reflects the broader literature that suggests that the carework of food provisioning is gendered, and that this gendered labor can be both challenging, and rewarding.

FOOD PROVISIONING STRATEGIES

There are a range of strategies that farm workers may utilize to address the constraints they face in providing food for themselves and their families. Below we briefly highlight some of the strategies discussed by our research participants.

Headstart

Most of our research participants are in some way connected with a local Headstart program geared for farm working families. The children who attend the school get breakfast and lunch at the school, which is a great benefit to Latina farm workers in their food provisioning labor. One respondent mentioned that breakfast is key for kids of farm workers. They have to report to the fields so early in the morning, that is a great relief to know they can drop the kids off and they will get breakfast at school.

SNAP, WIC, and Food Banks

Nationally, 50 percent of the farm workers reported that they or someone in their household uses at least one type of public assistance program. The programs most commonly utilized were Medicaid (37%), WIC (18%), and food stamps (16%). This data was reflected in our own findings; among those we have interviewed, all have reported utilizing supplemental food programs or knew of other family members utilizing these programs. Among our survey respondents, just over 50 percent reported utilizing SNAP and WIC.

School Meals

According to data from the Idaho Department of Education, 98 percent of families in Wilder, which is the main town in the heart of hops country in Idaho, qualify for free or reduced priced lunches. This is compared to 50 percent of children statewide. The school district in Wilder has been able to become a Community Eligibility Provision school district. This means that all children are provided free school meals, regardless of eligibility. Our data suggests that this program, which can also include preschools, is a great benefit to women working in Idaho agriculture.

Food Sharing

During our initial fieldwork, we observed a great deal of food sharing among rural families. These informal networks (for example, farm owners sharing crop harvests with their worker) are important to the women farm workers we interviewed. People also report sharing food with neighbors and extended family, as well as receiving food from the farms where they are employed.

PARTING THOUGHTS

Our research is motivated by a desire to understand the transitions in farm labor occurring in Southwestern Idaho. Due to geographic, cultural, and economic isolation, concerns about the health and well-being of farm workers are often overlooked. Focusing on food provisioning allows us to connect with women who might otherwise be passed over in scholarly research on farm labor. We find that many of the challenges the women face are related to intersections between socioeconomic status, which includes certain characteristics of farm work, family dynamics and race and ethnicity.

Acknowledgments

Pilot Research has been supported by the receipt of a small research grant program from The School of Public Service, Boise State University. Research has also been supported by Casita Neptanla and the College of Arts and Sciences at Boise State University. The authors also thank Clariza Arteaga and Anna Zigray, (Boise State undergraduate students) for their research assistance.