Of those men who have overturned the liberty of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by playing obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues and ending tyrants.

—Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 1

When the delegates to the Constitutional Convention gathered in Philadelphia during 1787 to craft a new system of governance for the United States, they drew upon their knowledge of history to identify potential dangers that might one day undermine the republic. The founding fathers believed that understanding the problems that marred previous experiences with citizen-centered rule would alert them to the perils that America could face in future. Foremost among their concerns was the threat that demagogues posed to civil discourse and democratic norms.

Arousing Passions and Appealing to Prejudices

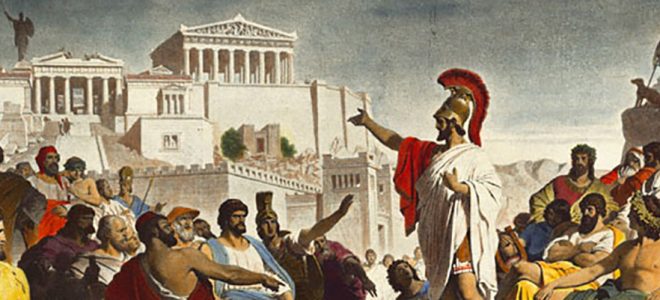

The term “demagogue” (dēmagōgos) arose in Greece during the fifth century B.C.E. to describe a new breed of charismatic politicians who sought to lead the masses by arousing their passions and appealing to their prejudices. In contrast to political figures who advocated courses of action that they believed were in the common good, demagogues used their rhetorical skills to promote policies that advanced their self-interests. In ancient Athens, those skills were used when speaking before the Assembly (Ekklēsia), which met forty times a year on the Pnyx Hill above the city’s bustling marketplace. After speeches were delivered on an issue, the Assembly would vote and pronounce a decree, which was then implemented by magistrates and boards appointed by lot for yearlong terms. Because under the principle of isegoria (freedom of speech) all adult male citizens had an equal right to participate in Assembly deliberations, education in persuasive speaking was popular among Athenians. Gorgias of Leontini, Hippias of Elis, and Protagoras of Abdera were among the most famous itinerant teachers, known as sophists (“men of wisdom”), who offered instruction in the art of rhetoric.

Pericles, the leading general and statesman of the period, mirrored the pride that Athenians had in their tradition of civic engagement. “Our ordinary citizens,” he proclaimed, though occupied with the pursuits of industry, are still fair judges of public matters; for, unlike any other nation, …instead of looking on discussion as a stumbling block in the way of action, we think it an indispensable preliminary to any wise action at all.”

Following the outbreak of plague in 430 B.C.E., Athens fell under the spell of demagogues who flattered the common people and vowed to make them “winners.” Cleon, the most notorious of these individuals, was described by the biographer Plutarch as “a fellow remarkable for nothing but his loud voice and brazen face.” The son of a wealthy leather tanner and merchant, he was seen by blue-blooded Athenians as coarse and vulgar. Like an outer-borough New Yorker rebuffed by Manhattan patricians, Cleon was spurned by Athens’ social and cultural elites. He disparaged intellectuals, belittled critics, and lashed out at adversaries, once apparently threatening to prosecute Callistratus, producer of the play Babylonians, claiming that the performance slandered the state. Although Cleon received an inheritance upon his father’s death, Critias, a controversial Athenian poet, insinuated that he was mired in debt and only recovered after leveraging his political position for personal gain. Knights and Wasps, satirical comedies written by Aristophanes, also implied that Cleon was corrupt, though we possess less evidence about his alleged venality than we have regarding his insolence.

Bluster and Bravado

Whereas Cleon was heralded by his supporters for speaking frankly (parrhēsía)—ostensibly, “telling it like it is”—Aristotle demurred that on the contrary bluster and bravado typified his oratory: “He was the first who shouted on the public platform, who used abusive language and who spoke with his cloak girt around him, while all the others used to speak in proper dress and manner.” The historian Thucydides added that Cleon was the most violent man in Athens, someone prepared to brand those who disagreed with him as “enemies of the people.”

During the fourth year of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta (431-404 bce), when Mytilene, the principal city-state on the island of Lesbos, attempted to break its military ties with Athens, Cleon urged the Athenians to kill the city’s men and enslave the women and children. The Mytilenians were disloyal, he thundered. They deserved harsh punishment. Not only would this be just, but it would deter others from betraying Athens. Even though the Athenian Assembly chose not to heed his counsel, over the next few years Cleon goaded its members into adopting a more aggressive strategy toward Sparta. He persuaded his fellow citizens to assault the Spartan position on the island of Sphacteria and reject any peace offers; he convinced them to demand a larger contribution to the war effort from Athens’ allies in the Delian League; and he recommended that they execute the adult male inhabitants of Scione, a city that had revolted against Athens.

Ironically, despite his inexperience in armed conflict, Athenian forces under Cleon’s command succeeded in capturing several towns in the Chalcidice. But his ineptitude contributed to their failure to take Amphipolis, an important naval base that controlled access to timber, mines, and grain. Though he was accused by some of cowardice during the battle for the city, we lack independent corroboration of allegations about his behavior under fire. However, what the record does indicate is that Cleon was a shamelessly arrogant politician and mediocre military tactician who fraudulently promised to make Athens great again.

Cleon and the other demagogues of ancient Greece are removed from us by over two millennia. Their stories are intriguing, but what insights can we gain from them that might promote a better understanding of the political challenges of our day? Of course, the past never exactly presages the future, but examining history in a careful, discriminating way can help us think more deeply about the present.

Dangers to Democratic Governance

By rebuking would-be tyrants who manipulated the anxieties and resentments of the crowd, the historians, playwrights, and philosophers of antiquity have forewarned us of the dangers that demagogues pose to democratic governance. Uppermost among these dangers is what demagogues do to civic life. Although, as Plato observed in the Republic, demagogues portray themselves as “protectors of the people,” they widen social cleavages by peddling conspiracy theories, playing one group of citizens against another, and by singling out scapegoats to blame for both real and imagined problems. They further degrade public discourse by hurling insults and spurious allegations at anyone who dares to challenge them, attempting to cow opponents into silence. Demonizing the opposition, denying its legitimacy, and calling for its leaders to be locked up undermine the prospects for fair, inclusive, and competitive elections. Within this toxic climate, political divisions become almost impossible to bridge, which dissuades elected officials with differing viewpoints from deliberating together.

Thucydides presents a shocking description of what can happen when a society becomes polarized and political debate is infected by mutual loathing. During the fifth year of the Peloponnesian War, he depicts how Corcyra, an island located in the Ionian Sea, descended into a hellhole of civil strife. In the mayhem, political rivals became mortal enemies, with partisan loyalty transcending the bonds of family, religion, and ethnicity. Language was perverted as words lost their ordinary meanings. Recklessness came to be seen as courage, prudence as cowardice, and temperance as weakness. Extremists were considered honorable; moderates, traitorous. Piety and law were distorted for factional ends, as militants in each camp disavowed common moral ground.

When language is debased, and conventions governing honest discourse weaken, demonstrably false claims presented as “alternative facts” increasingly contaminate policy discussions. “What you are seeing,” demagogues tell the populace, “is not what is happening.” “Truth,” their apologists assert, “isn’t truth.” Deliberately employed to sow doubt about what to believe, incessant falsehoods overwhelm listeners and beget resignation, inducing people to live public life as passive subjects rather than as active participants. In this environment of uncertainty and suspicion, civic trust erodes and the normative pillars of democracy—tolerance, forbearance, and compromise—crumble.

America’s founders recognized that modern demagogues, like their ancient predecessors, posed a serious problem for democratic governance. Armed with beguiling words but bereft of realistic plans for solving social and economic problems, demagogues hope to capitalize on the chaos they provoke. Writing in Federalist No. 68, Alexander Hamilton cautioned against any “man unprincipled in private life” and “bold in his temper” who would “throw affairs into confusion that he may ‘ride the storm and direct the whirlwind’.” Rather than embodying what the Greeks called sōphrosunē—discretion and self-control—such a person, Hamilton feared, would act impulsively and “fall in with all the nonsense of the zealots of the day.”

The founders believed that the Hellenic world’s experience with demagogues was worth pondering because the ancients wrestled with questions about the advantages and drawbacks of rule by the one, the few, and the many. Demagogues would occasionally gain power in democratic political systems, the Greeks acknowledged; nevertheless, no matter how entrenched such aspiring tyrants might seem, their footing remained insecure. Deep-seated character flaws ultimately would trip them up. Individuals who unendingly boast of their intelligence and wealth, who traffic in malice and divisiveness, and who bully and humiliate others, show symptoms of hybris—unbridled arrogance.

“All arrogance will reap a harvest rich in tears,” warned the tragedian Aeschylus. His portrayal in Persians of King Xerxes’ catastrophic losses at Salamis to a smaller flotilla of Greek warships underscores the heavy reckoning ordained by overweening pride. Those suffering from hybris lack the capacities for empathy and introspection. Callous and unreflective, they succumb to atē, the commission of an outrageous, morally blind act that leads to their fall, or nemesis. “A man’s character,” concluded the philosopher Heracleitus, “is his fate.”

Gregory A. Raymond is Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Boise State University. A former Pew Faculty Fellow at Harvard University, he has published 17 books and over 100 articles, essays, and reviews on world politics and foreign policy, and has spoken on international issues at universities and research institutes in 22 countries. In addition to receiving numerous research and teaching honors, he is a past recipient of the Idaho Professor of the Year award from the Carnegie Foundation.

Gregory A. Raymond is Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Boise State University. A former Pew Faculty Fellow at Harvard University, he has published 17 books and over 100 articles, essays, and reviews on world politics and foreign policy, and has spoken on international issues at universities and research institutes in 22 countries. In addition to receiving numerous research and teaching honors, he is a past recipient of the Idaho Professor of the Year award from the Carnegie Foundation.