Steven Feldstein is an Associate Professor and holder of the Frank and Bethine Church Chair of Public Affairs at Boise State University. He is also a nonresident fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Democracy and Rule of Law Program. His research focuses on U.S. foreign policy, counterterrorism, democracy and human rights.

Civility took a hit last year. The turbulent, racially charged events of 2017 reverberated in a manner not seen since the sixties and seventies. Skirmishes and melees broke out across the country, from Berkeley to Boston. Neo-Nazis and white supremacists marched by torchlight through a southern college town. Rightwing militia members, armed to the teeth, menacingly stared down peaceful citizens. Tensions boiled over, a car plunged into a crowd of protesters, and when the smoke cleared an innocent activist, Heather Heyer, lay dead on the ground.

That tragic August weekend in Charlottesville underscored months of unease and tension in the country. It laid bare fundamental questions about the depth of polarization in communities across the United States, and what level of violence will be tolerated in a fight against intolerance.

These incidents have also led many to question whether traditional norms of civility – of politeness, courtesy, and respect – have vanished completely from American political discourse.

Along with the rise of right-wing extremist groups, a left-wing coalition—antifa—has started to receive increased attention. Its name derives from “anti-fascist,” and its membership is made up of a diffuse network of leftwing activists who openly use violent tactics to counter rightwing aggression. Their goal is to deny right-wing extremists a voice and platform. Antifa made headlines from the beginning of 2017, when an activist punched prominent white supremacist Richard Spencer in the face right after President Trump’s inauguration, spawning a debate about whether it was acceptable to punch a Nazi.

Antifa presents a difficult quandary for those struggling against right-wing extremism. On the one hand, using violence to fight back against a hateful and violent movement feels justified, especially when confronting specific and imminent harm. As Cornel West described the events in Charlottesville, “those twenty of us who were standing, many of them clergy, we would have been crushed like cockroaches if it were not for the anarchists and the anti-fascists who approached, over 300, 350 anti-fascists. We just had 20…The anti-fascists, and then, crucial, the anarchists, because they saved our lives, actually. We would have been completely crushed, and I’ll never forget that.”

“When confrontation shifts to the arena of violence, it’s the toughest and most brutal who win—and we know who that is.”

On the other hand, as Noam Chomsky points out, ”When confrontation shifts to the arena of violence, it’s the toughest and most brutal who win—and we know who that is. That’s quite apart from the opportunity costs—the loss of the opportunity for education, organizing, and serious and constructive activism.”

As citizens, we have an obligation to understand and weigh what is gained and lost when political movements embrace fringe viewpoints and resort to violence. Sadly, this is not a new issue for the country. Back in the 1960s, for example, Senator Frank Church regularly decried the emergence of the “Radical Right,” warning that the fear generated by such groups was undermining public trust in government institutions, and that when “mutual confidence is destroyed, then we shall have cause to fear the loss of freedom in America.”

Ultimately, I believe that the political and social costs to pursuing violent campaigns substantially outweigh any short-term benefits.

EFFECTIVENESS OF NONVIOLENT APPROACHES

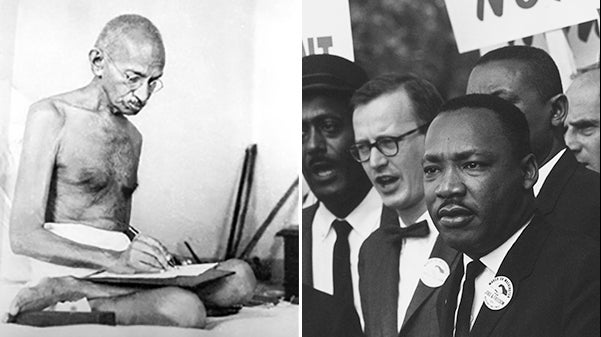

A large body of research – including case studies from Mahatma Gandhi’s campaign for India’s independence, the U.S. civil rights movement, and South Africa’s anti-apartheid campaign – indicates that nonviolent action is often more effective than violent campaigns in achieving political objectives.

Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan have undertaken one of the most comprehensive recent studies of worldwide violent and nonviolent campaigns. They found that nonviolent campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success in contrast to violent movements, even when taking into account regime types, regime repression, and target regime capabilities.

Other research shows that violent protests and riots can undermine broader public support and lead to more restrictive policies. Omar Wasow studied black-led protests in the United States from the 1960s. He found that peaceful civil rights protests initially broke elite dominance of communication and influenced national discourse. However, when rioting took hold, this negatively influenced public opinion and likely tipped the 1968 presidential election to conservative Richard Nixon.

In a similar vein, the anti-government Patriot movement was ascendant in the United States in the early 1990s. In 1995, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols planned and executed the bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people and injuring many more. While no direct links were found between the Oklahoma City bombers and the broader militia movement, the public associated them together and “the image stuck of militia members as mad bombers.” Subsequently, the Patriot movement went into significant decline. Six years after the bombing, the number of identified “militia” groups cratered from a peak of 370 to 68. While the movement has experienced a subsequent resurgence, it took years for it to regain strength.

When it comes to why groups choose to pursue nonviolent actions, there are two major schools of thought – the “principled” and “pragmatic” camps. The principled camp, epitomized by Mahatma Gandhi, maintains that there is an inherent moral virtue to exclusively pursuing peaceful means to attain political objectives. They argue that violence taints the movement and undermines the moral legitimacy of the struggle.

In contrast, the pragmatic camp, represented by the late Gene Sharp, contends that both violent and nonviolent campaigns aim to influence behavior and to make “somebody do something or not do something or stop doing something.” Political scientist Thomas C. Schelling agrees: “Both can be misused, mishandled, or misapplied. Both can be used for evil or misguided purposes.” For Sharp, nonviolence represents a tactically superior way to accomplish diverse political objectives. His list of 198 methods of nonviolent action—from symbolic public acts to economic boycotts—is widely emulated.

So what characteristics make nonviolent campaigns successful? A report from the U.S. Agency for International Development asserts that successful movements consciously use framing narratives to advance their causes: “absent an effective story that can draw in active civil society support, grassroots advocacy for human rights protection is likely to falter and fail.”

In Russia, for example, protests arose in the early 2000s against Vladimir Putin’s war effort in Chechnya. The antiwar movement underwent a sharp internal debate about whether to change its messaging to appeal to a wider audience or to keep using a narrower human rights frame, which was demonstrating decreased appeal. The traditionalists won the day. The campaign abandoned efforts to reach out to younger protesters, and declined to shift its narrative from a western human rights orientation (“Russian actions violate Chechen human rights”) to a Russian nationalist argument (“end the war, our soldiers are dying for nothing”). Consequently, the campaign was unable to attain broader support and its efforts fizzled.

Unfortunately, antifa activists are notoriously reluctant to explain their position. As Daryle Jenkins, an antifa activist, relates: “If you want to know what antifa is about, talk to antifa—if you can find people in antifa that will talk.” If antifa refuses to provide a narrative to justify their action, its opponents are more than happy to define antifa for the public.

COUNTERARGUMENTS TO NONVIOLENCE

Despite increasing research detailing the effectiveness of nonviolent strategies, several important counterarguments exist.

First, the bulk of research examining nonviolent payoffs focuses on campaigns related to removing “incumbent national leaders” or gaining “territorial independence.” While there is much to learn from these types of movements, they are qualitatively different from non-government movements confronting other non-government movements, such as antifa squaring off against white supremacists or neo-Nazis.

Second, while many commentators cite the rise of National Socialism in Germany as a cautionary tale about the perils of using violence to confront violence, the similarities are dubious. The general argument proceeds along the following lines: as Nazis and left-wing socialist groups faced off in Germany, the public became increasingly alarmed by the rising tide of violence. Support for left-wing groups cratered as the public embraced law and order approaches associated with the Nazis. While this example has a certain intrinsic appeal, its contemporary relevance is misleading. For one, left-wing parties in Germany were not pluralist liberals seeking to staunch a fascist tide. Instead, they were communists who had attempted an armed takeover of the German government in 1919 and 1920, and who were riven by factionalism and dissension. When clashes between the Nazis and communists began, such as the 1927 Nazi rally in the German city of Wedding, the Nazis were still on the political fringes. It would be another six years before Hitler ascended as Chancellor of Germany. What violent confrontations in this period actually suggest is not that violence backfired; rather, that the Nazis were more adept at manipulating violence towards their own political ends. It is also worth remembering that Germany in the late 1920s was a humiliated, defeated country suffering from massive economic woes and hyperinflation. The Weimar Republic was exceptionally weak and Germany’s citizens were accordingly vulnerable to fascist messaging. Moreover, the virulent, ethno-nationalist rhetoric espoused by the Nazis was a new phenomenon for Germany. The world had not witnessed the implications of Nazi rule. In contrast, we now have decades of lessons and research about Nazi ideology. It is hard to imagine that violent antifa tactics today would all of a sudden lead to a newfound embrace of fascism.

Third, not all protest movements can be strictly classified as “violent” or “nonviolent.” Many successful movements have embraced a diversity of tactics, such as the ANC and the IRA. The same can be said about antifa. In addition to pursuing violent tactics, antifa often undertakes peaceful actions as well. For example, Mark Bray notes: “Most of what antifa groups do is nonviolent. Most of it has to do with research and monitoring and tracking and making phone calls to venue owners and organizing boycotts against the American Legion that are hosting white power rock events. So the spectacle of confrontation is really usually a last resort, when other methods have failed, to disrupt these groups.” Nonetheless, researchers such as Jonathan Pinkney caution that even “scattered incidents of violence can ‘crowd out’ largely nonviolent movement’s impact and decrease participation in civil resistance.” Likewise, research by Chenoweth and Kurt Schock concludes that while “violent flanks” of larger movements may help to achieve short-term “process goals,” they tend to undermine long-term strategic objectives, particularly expanding broad-based public support.

Fourth, while the number of nonviolent campaigns around the world has risen, their success rate has plunged, from a high of nearly 70% in the 1990s to only 30% between 2010-15. While the success rate of violent campaigns has similarly declined, this nonetheless represents a warning sign for the perceived efficacy of nonviolent approaches.

Not all protest movements can be strictly classified as “violent” or “nonviolent.” Many successful movements have embraced a diversity of tactics, such as the ANC and the IRA.

SOMETIMES VIOLENCE PAYS OFF

The use of force is deeply enshrined in western liberal thought. Political theorist Christopher Finlay observes that both Thomas Paine (“it is the violence which is done and threatened to our persons … which conscientiously qualifies the use of arms”) and John Locke (“That force is to be opposed to nothing but to unjust and unlawful force”) rationalize the use of force to combat tyranny and grave injustice. In fact, Finlay opines that if “the left too eagerly rejects the idea that armed resistance can ever be justified,” then in a hypothetical scenario in which a violent outbreak does occur – however minor – the left runs the risk of immediately conceding its moral standing.

Political scientist Benjamin Ginsberg similarly notes: “For better or worse, violence usually provides the most definitive answers to three major questions of political life: statehood, territoriality, and power. Violent struggle—war, revolution, terrorism—more than any other immediate factor, determines what nations will exist and their relative power, what territories they occupy, and which groups will exercise power within them.” Ginsberg advises that the key difference between a successful nonviolent campaign, such as the U.S. civil rights movement, and an unsuccessful one, such as the Tiananmen Square protests, is that the civil rights movement had allies with an even higher capacity for violence than their adversaries – i.e., a phalanx of federal law-enforcement officials “with the power to suppress white resistance to the registration of black voters.”

Some research puts less of a premium on whether demonstrations are violent or nonviolent and instead focuses on protest size. Mark Lichbach notably established the Five Percent Rule: no government can survive protests when more than five percent of the national population is mobilized against it. Chenoweth and others would argue that the determining factor for whether movements could attain mass scale would depend on whether they were violent or nonviolent. However, Dawn Brancati finds that participants not only acted violently in about half of all democracy protests between 1989 and 2011, but “protests in which the demonstrators acted violently were larger, drawing more participants at their largest rally, than those in which the protesters were not violent.” She notes that in the majority of protests that threatened the stability of governments – those with participation exceeding one hundred thousand – protesters also acted violently.

While employing violent tactics do not necessarily lead to better outcomes, it is a debatable question whether nonviolent campaigns are always superior to violent movements.

RESISTING THE URGE TO PURSUE VIOLENCE—FOUR KEY PRINCIPLES

Even if violent protest tactics can sometimes lead to successful outcomes, there is a compelling reason to be wary of antifa’s violence: the correspondingly high social cost associated with movements that espouse violence. Not only do violent movements lay the groundwork for future instability, but research shows that where violent insurgencies have come to power, “democracy is less likely to develop than in similar cases where nonviolent resistance succeed.”

Nonetheless, the appeal of violence is very strong. As Michelle Goldberg writes: “If people believe that their government hates them and established institutions are incapable of staving off fascism, they will inevitably take matters into their own hands, whether that means exposing people online or fighting with them offline.”

Part of what may explain resurgent explorations of violence is that the left faces a real crisis of political power. But leftwing dalliance with violence is precisely the wrong response to counteracting extreme rightwing ideology and reclaiming political power. Instead, activists would be better served pursuing the following principles, which are drawn from the research of successful protest movements.

First, widen participation as broadly and inclusively as possible. The level of sustained citizen participation is closely linked to movement success or failure. In particular, those citizens who self-identify as moderates or independents—who are generally turned off by liberal protests—are a crucial bloc. Taking a stand against the KKK or neo-Nazis should not be a partisan issue. The most effective way to counter right-wing hate groups would be to bring together a broad coalition of liberals and conservatives to repudiate violent behavior. If public opinion strongly shifts against white supremacist ideas and attitudes, this will force the government to crack down more resolutely on rightwing violence, and it will limit the president’s leeway to equivocate on the issue.

Second, as tempting as it is to match violence with violence, research indicates that violent campaigns tend to underperform nonviolent movements. Protest groups would be wise to maintain the moral high ground and forswear violence. This will not only enhance their legitimacy among a broader swath of people, but it is also more pragmatic. Gene Sharp’s 198 methods of nonviolent action represent more than enough options to effectively advance a liberal agenda. Likewise, Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler have distilled twelve principles of nonviolent action linked to strategic success. Among the most relevant: cultivating sources of external support through approval and empathy, minimizing the impact of the opponent’s use of violence, and using the adversary’s own actions to alienate their supporters, such as publicizing the opponent’s violent repression of nonviolent resistors.

One successful tactic has been to mock violent rightwing groups rather than directly confront them. In 2014, the “Right Against the Right” campaign in Germany created a fundraising walkathon to accompany an annual Neo-Nazi march in Wunsidel, the original burial site of Rudolf Hess, one of Hitler’s deputies. For every meter the Nazis marched, local businesses and residents pledged money towards an anti-violence NGO. Residents adorned the route with humorous signs and jokey slogans, and turned the event into an absurd spectacle, blunting the Nazis’ symbolism and undercutting their impact.

Third, activists should employ aggressive framing and reinforce negative narratives about opponents. They would be best served by focusing attention on the menacing threat of extreme right-wing groups, while emphasizing the nonviolent, nonpartisan nature of their own movement. The example of the Dalit movement is instructive. For decades, those identified in low caste groups—numbering approximately 250 million worldwide—faced rampant and systemic discrimination in India and elsewhere. Despite years of effort, the international community consistently failed to understand the Dalit’s cause as a human rights issue. Finally, activists undertook a series of changes. They began emphasizing the scale of human rights abuses occurring on a daily basis. They also took steps to counter government claims that the problem was merely a social custom, rather than governmental inaction; the activists recognized that it is easier to “spark international action around de jure discrimination and violations by state authorities, than de facto discrimination by private actors.” As a result, newfound international attention and more vigorous attempts to address discrimination and violations against the Dalit community are occurring.

Likewise, the most effective moments for the civil rights movement and anti-war protests in the sixties and seventies were massive demonstrations that attracted millions of supporters – and corresponding violent responses by the government. When the National Guard fired on student protesters at Kent State University, and when Alabama state police set water cannons and dogs against demonstrators on national television, the protest campaigns had won.

Fourth, don’t let internal divisions supersede organizational goals and innovation. When individual aims supplant broader objectives, then a movement faces serious risk. This becomes especially relevant when recruiting participants who are less familiar with and less vested in the goals of the campaign. As Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham, Marianne Dahl and Anne Frugé note: “only a subset of individuals will be willing to mobilize, and among those, each person will have a limited amount of time, attention and energy they are willing to devote to the cause.” Although it is important to have a full and vigorous discussion about antifa, it would be unfortunate if this debate ended up splitting activists, displacing larger issues, and turning off potential support.

LET HISTORY BE YOUR GUIDE

After a year full of shocks and surprises, activists may be tempted to break the old rules and try something new. But violence always comes with a prohibitive cost. We should remember that the United States has gone through such divisiveness before. Fifty years ago, violent offshoots from the U.S. anti-war movement embraced confrontation as the right answer.

Decades later, though, one of those activists who had embraced violent tactics regrets that choice. Weather Underground member Mark Rudd laments: “I had purposely excluded the millions of moderate, nonviolent, middle-of-the-road people who now were willing to publicly demonstrate their opposition to the war. I denounced anybody…who proposed a broader action, with less militancy and violence, as a ‘liberal,’ a very dirty word at the time.” The results were ugly and tragic. The arson and bombings organized by the Weather Underground brought lasting damage to the left’s political agenda and generated a major backlash. Citizens face analogous choices today. As debates continue about whether to adopt violent tactics and whether to support antifa, it would be wise to look carefully at what history and research show.